Outlook 2017-2020: Robots, Automation & Industry

Labor costs, global competition, national initiatives, and innovation demands, drive Asia’s investments in robotics to the max

Yes, “It’s all about economics”

My Lanesboro, V-neck, T-shirts are made in India, but they may not be for very much longer, according to a dour 34-page report by UBS on shrinking globalization and its outcomes.

Here’s the long view:

Notice the “Slowdown” in the above chart?

Combine that report with the near-giddy 2016 forecast from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) that heralds skyrocketing global robot sales through 2020, and it’s clear that making Lanesboro T-shirts may soon go to a robot-driven, automated smart factory in New Jersey.

And why not? The T-shirts would then be much closer to me, the consumer, and closer to BJ’s where I buy them for $8.99 for a pack of six.

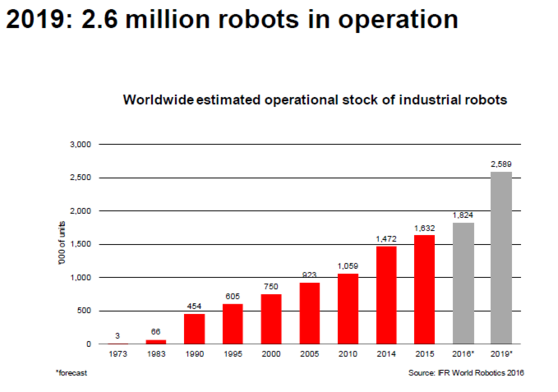

Then there’s over a million new robots joining the workforce by 2019, which, according to Joe Gemma, president of the IFR, represents a 59 percent increase since 2010 (1995-2005 represented a 20 percent increase).

Viewed on a cross-sector basis, the international market value for robotic systems now lies at around $32 billion.

As FT Alphaville commented: “In short, sourcing product from half way around the world isn’t necessarily a value add activity in the aggregate if the key justification for the added complexity and transport costs are cheap labor resources…should we really be surprised then that global supply chains are shrinking?”

Given the above, shipping stuff half way across the world simply doesn’t make sense, especially with supply chains that are too long, too complex and too fragile…not to mention their woeful carbon footprint.

All of which means that Lanesboro T-shirts made in India should be sold in India or to its neighbors in Southeast Asia. Since a topflight engineer in India makes $9,000 per year, he won’t anytime soon order $8.99 a-pack T-shirts from Flipkart.

To be affordable to that engineer, the factory would have to manufacture for less, which means robot-driven automation needs to happen at that Indian shirt maker, which is not going to happen anytime soon because of lack of investment capital, either from the Indian government or from private investment. Foreign investment capital, like FDI (foreign direct investment), is drying up as supply lines shrink and robots go to work, according to the same USB report.

Diminishing FDI is also about the “reduction in growth-creating real trade.”

As UBS’ Paul Donovan and Sophie Constable put it: “There is a war for capital coming: International capital is harder to come by. Countries without sufficient domestic capital will have to fight to finance their current account deficits, especially if they are unattractive locations for real world direct investment.”

The mountain to climb and China’s gambit

The Lanesboro dilemma is what China is racing to put way back in its rearview mirror.

That race is what IDC Manufacturing Insights reveals in a report titledRobotics in China Industry as showing that the adoption rate of robotics in China’s manufacturing industries will grow by 150 percent by 2018.

That’s why Joe Gemma and the IFR are so giddy.

“The rise of robots in China can be attributed to three pull and push factors respectively”, said Dr. Jing Bing Zhang, Research Director, Worldwide Robotics and Asia Pacific Manufacturing Insights, IDC Asia/Pacific.

“The three pull-factors are the rising labor cost, increasingly aging population, and global competition, whereas the push-factors are national initiatives, innovation, and investment in robotics,” added Zhang.

China has made it well known that its “Made in China 2025” campaign will leapfrog the country into a global power in the manufacturing of advanced technology rather than cheap, and often imitated, merchandise.

China has also announced that to carry out that leapfrogging it will finance the means to “develop innovative R&D, train skilled workers, and upgrade factories to include more automation and robotics.”

To that end, as John Gapper’s recent article in the Financial Times so bluntly puts it: If China cannot beat Europe, it will acquire it. To offer a sense of what Gapper is talking about here: According to Dealogic, last year (2015) was a record-breaker for Chinese outbound deals, with 607 deals valued at $112.5 billion in total. With some$3.5 trillion in foreign currency reserves,China could keep buying tech for a long time.

See backgrounder: 2017-2020 Robotics: The Big Breakout!

To climb that mountain successfully, China will need to up its robot density from 36 units per 10,000 workers to at least double the global average of 66 (Portugal has 42 robots per 10,000 workers). In comparison, Korea, the world leader, has 478 units per 10,000 workers, Japan (314 units) and Germany (292 units).

China’s unparalleled game of catch-up will get it to 150 per 10,000 workers by 2025, which is the main cause of Joe Gemma’s glee. The IFR calculates that China will need to deploy some 600,000 to 650,000 new industrial robots in order to pull off the 150 ratio.

As the IFR reports: “Never before have so many robot units been sold in one year as were sold in China in 2014 (57,100 units). The boom is continuing unabated in line with the forecasts: In 2018, China will account for more than one-third of the industrial robots installed worldwide.

“With sales of about 68,600 industrial robots in 2015 – an increase of 20 percent compared to 2014 – China alone surpassed Europe’s total sales volume (50,100 units).” Now, however, a growing percentage of those robots are actually domestically produced by China’s own indigenous robot builders (China’s aim is 50 percent home built by 2025).

The gambit being played is two-fold: 1. China to become the aforementioned global manufacturing powerhouse of high-value technology products; and 2. China to become the central supplier of low-cost, robot-driven automation to Southeast Asia, but more importantly, to India.

Automation in India would allow our $9,000 per year engineer to buy Lanesboro, as well as millions of others to upgrade their undies.

The cobot sleeper awakens

Although they represent less than 5 percent of the record 253,748 units sold in 2015, cobots, short for collaborative robots, are big-time productivity sleepers now awakening at scale into manufacturing. They have the potential to revolutionize production, in particular for the smaller companies (SMEs) that account for 70 percent of global manufacturing.

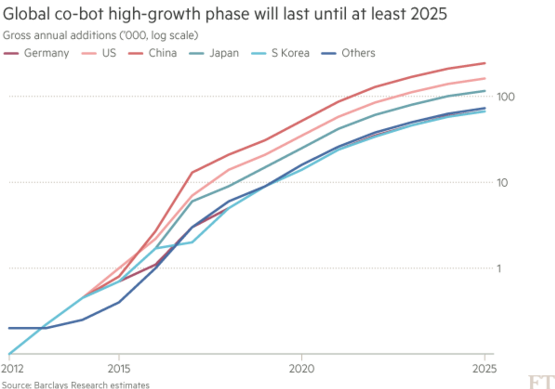

James Stettler, an analyst at Barclays Capital, “estimates the cobot market could grow from just over $100 million last year to $3 billion by 2020.”

“Scientists at the MIT…working with German carmaker, BMW, found that robot-human teams were about 85 percent more productive than either alone.” That’s great news for global productivity, especially for the productivity challenges looming for China.

This cobot growth chart shows the striking rise ahead for cobots (barely a three-year-old robot category):

Cobots took most manufacturers by surprise after Universal Robots first introduced its UR10 in 2012; end users were even slower to catch on to the huge potential that these new robots presented to their businesses. Not any longer. Even heavyweight FANUC, originally one of the last to get on the cobot bandwagon with a product, is now a full-fledged believer.

Penetration of cobots in Asia has been marginal throughout 2016. Look for dramatic change throughout 2017 and beyond.

Warehouse woes

Similarly, logistics robots, both for moving goods as well as for picking and packing goods is virtually non-existent in Asia. China, with seven of the ten busiest ports in the world has by far the worst warehouses in Asia.

A recent Prologis study of Asian warehouses reports on ageing structures throughout Asia badly in need of upgrading if they are to be as productive as China, Japan and Korean claim they want their logistics systems to be.

See warehousing: Robots and the Great Asian Warehouse Makeover

Logistics finally capitulates to robots in the West, but biggest gains to be felt in Asia. Look for 2017 to be huge!

The robot rush to Asia: 2017-2020

The Asian Century for robot-driven automation launched itself into high gear in 2016. China will aim for the homeland and building out its manufacturing infrastructure with more zeal than it originally did rushing to be the world’s factory.

Japan will take dead aim at the Factory of the Future and worldwide standards for such factories, as well as delivering major automation capabilities to Southeast Asia.

Korea during 2017 will continue its automation hegemony with its newest, best friend, Vietnam.

See Asia’s future: 2017-2020: The most important four years in the history of robotics have begun

The scorecard beyond industrial robots

Professional Service robots (IFR stats):

1. Medical: in diagnosis, surgical assistance and rehabilitation—sales value is expected to rise to $ 7.2 billion.

2. Agriculture: (agribots) an increase up to $ 5.7 billion is expected.

3. Logistics: In the logistics systems – with the major share of automated guided vehicles (AGV) – a sales value of $ 5.3 billion is expected.

Demand in the logistics has already seen strong growth from 2014 to 2015. The number of units sold rose by 50 percent to 19,000.

The sales value surged during the same period by 52 percent to $ 779 million. Based on the manufacturers’ market shares, 81 percent of the logistics systems are produced in the US—only 11 percent in Asia

(emphasis ours) and 8 percent in Europe.

Global robot market between 2016 and 2019:

1. 333,000 service robots for professional use will be sold to non- manufacturing and to manufacturing sectors.

2. 42 million service robots for personal and domestic use (consumer robots) will be used in private life; and

3. 1.4 million industrial robots will be installed in factories to increase productivity.