Hey World, Let's Get Going Again!

We Need Jobs, Reskilling & Reinvigorating

Workers and employers alike have COVID & robot fatigue; they have turned the page, and with clearer heads are now preparing for a bright new future

“We expect the momentum, especially at the beginning of the year, to pick back up in the job markets.

While we see high unemployment, we also see a lot of job openings.”—Manpower Group

Adding new facets to existing skills

Speed matters when it comes to enrolling into reskilling /retraining programs workers who were recently laid off. It’s especially so in the face of the COVID pandemic. Any significant delay—a wait of a year or more—often permanently hinders a worker’s chances at finding a new career and limits his or her lifetime earnings.

Reskilling/retraining is most successful when workers actually start it before they leave their old job. “If you wait until they are out of a job, the emotion of losing a job comes into play; they start to get accustomed to not working, they get rusty,” said Jane Oates, who was an assistant secretary in the Labor Department during the Obama administration.

A major development is that the pathway to retraining these days almost always runs through a college campus. Even most manufacturing jobs now demand some sort of education after high school.

“Enough!” has lately come the resounding global response after years of getting pushed around by spectre of automation. It’s here. Let’s deal with it.

Workers and employers alike have robot fatigue; they have turned the page, and with clearer heads, are now preparing for a possible bright new future. It’s not bomb shelters and bracing for the worst as it was in 2013 when the Oxford study, The Future of Employment, in a mere 71 pages, wiped out 702 occupations and 47 percent of the U.S. workforce.

Nearly seven years on, research studies are kinder and gentler, like the recent Manpower study, Humans Wanted: Robots Need You that surveyed 19,000 employers in 44 countries on the impact of automation on job growth in the next two years. “Upskilling is on the rise, with 76 percent of companies planning to upskill their workforce, up from 28 percent in 2011.”

“The focus on robots eliminating jobs is distracting us from the real issue,” said Jonas Prising, Manpower

Group Chairman & CEO. “More and more robots are being added to the workforce, but humans are too. Tech is here to stay and it’s our responsibility as leaders to become Chief Learning Officers and work out how we integrate humans with machines. Learning today cannot be done as it was in the past.

“That’s why at ManpowerGroup we’re reskilling people from declining industries like textiles for jobs in high growth industries including cyber security, advanced manufacturing and autonomous driving. If we focus on practical steps to upskill people at speed and at scale, organizations and individuals really can befriend the machines.”

That’s certainly a refreshing take on the robot revolution that’s been a long time coming.

ManpowerGroup interviewed over 37,500 employers in 43 countries and territories on hiring prospects for the first quarter of 2021.

More than 6,700 interviews were conducted with employers within the United States, including all 50 states, the top 100 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, to measure hiring intentions for the first quarter of 2021.

Reskilling as hidden gold

In actuality, corporate retraining and reskilling initiatives can be hidden gold for boardrooms to mine. As Brittany Stich, co-founder of Guild Education, explains: “As employers strive to retain and recruit their workforce, providing employees the opportunity to develop new skills and progress in their careers is one of the most competitive benefits companies can offer.

“Stich believes this benefit will become as common as healthcare and 401k’s, given that sixty-one percent of Americans under 30 expect that it will be essential to develop new skills at some point in their careers.”

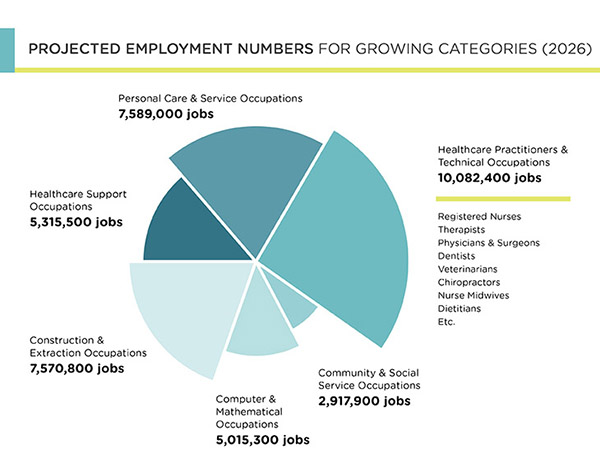

What jobs?

So, just what are these jobs for which employers will provide their employees with “the opportunity to develop new skills and progress in their careers”? As Pierce and Haythornthwaite write: “THE SKILLS GAP: It’s 2025. Do You Know Where Your Employees Are?”

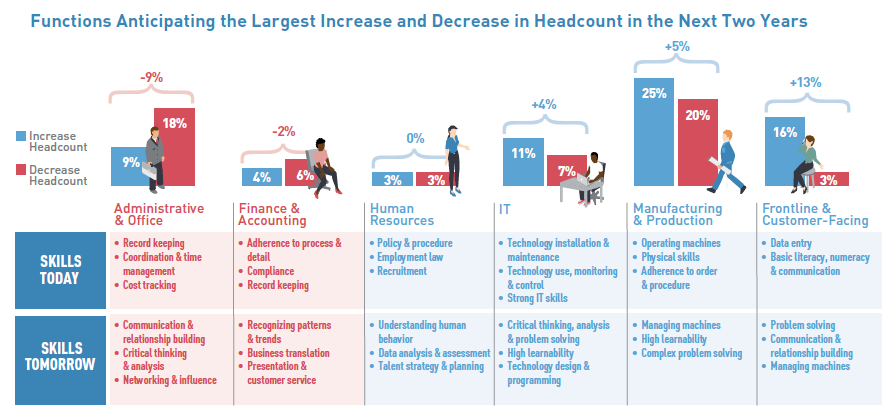

No doubt, those employees will be found somewhere in this “Skills Tomorrow” chart from Manpower.

As helpful as the chart is, employees want more than general categories and approximations. Employees are getting anxious about what exactly will be these future job titles, job descriptions, and salary ranges.

See related:

The Search for Compassionate Stakeholders

Eventually, Automation Will Make Every Job a Goner

Massive government interventions will be needed to retrain millions of workers for better jobs. Recently proposed legislation holds promise.

The reskilling process would be much more comfortable for them, if they had more facts about outcomes, if they could be a little more confident about career paths. Of course, answers to questions like those require a bit of a crystal ball…or maybe a well-trained AI.

As Arnold Pacey shows in his Technology and World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History, the history of technology always takes a while to show its hand, but when it does, it pushes out a deluge of new jobs that previously were unimagined.

The multi-million-person tech army called computer engineer, and even the ubiquitous electrician, were two such mega professions that came out of nowhere.

Pacey’s viewpoint on robotics, automation, and AI might be to expect the unexpected. Makes sense.

It takes time

In 1949, the brand-new occupation of electronic digital computer engineer was born (shortly thereafter, and thankfully so, it was shortened to computer engineer).

Back then, there were fewer than a hundred of such people. All were hardware engineers who programmed on their own in binary, most of whom in an old laundry building near MIT. Computer code wouldn’t come along for a few years yet.

Help wanted ads for this occupation often read: “Digital computer engineer wanted. No previous experience necessary or expected.” Reason being for “no experience” was simply that the technology was so new and embryonic that only the technology’s inventors knew much about it.

Not many new hires into computer engineering phoned home to mom elated about scoring a great job with tons of promise. Lots of moms must have been disappointed. The new technology’s staying power wasn’t given much of chance for success.

Fifty years previous, the occupation of electrician had come into being when steam-run factories began turning to electricity. Edison had opened his Pearl Street Power Station in 1882, but by 1900 barely five percent of America’s factories ran on the new power source.

The age of steam lingered on while electrification expanded to become mainstream, and electrician jobs slowly began to multiply. Computer engineering jobs grew more rapidly; the first computer engineering degree program in the U.S. was at Case Western Reserve University in 1971. That was some twenty-plus years after the occupation first hit the payroll department at MIT.

Steam-run factories, all of their workers together with all of their suppliers, went extinct, except for those that reskilled themselves to electricity. Many did; many didn’t. Business and job losses were massive and global.

Fifty years later, the same fate was dealt to analog computing and the mechanical tabulating industry, along with their employees and their suppliers, all of it arriving post-1949.

Help wanted ads for jobs in steam-run factories or, later, for making tabulating machines, disappeared from newspapers.

Robots, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI) are travelling a similar arc; this time, however, the tech is racing along at breakneck speed because the two basic ingredients necessary for its being—electricity and computing—are already in place and dominant.

It took the first two revolutions to make the third possible.

All three of these turbulent tech movements have experienced their fair share of negativity, including choruses from every quarter that the sky is falling and that job losses by the tens of millions are just up ahead.

However, at some point during each upheaval, after the initial shock begins to wane, people stop looking for the sky to fall, and begin the process of recovery and moving ahead with their lives and futures.

Here in 2020, faced with a global pandemic, change is just beginning to take place. The disruptor cometh, but reason, faith in the future, and remedies to survive and thrive are gaining momentum.

There are jobs on the other side of the pandemic, but getting ready is all important.

Humans are critically important

Just as in the making of electricians and computer engineers before them, new occupations are headed our way that we known nothing of. Some of these new jobs will spring up at us, others will quickly evolve directly out of the automation’s disruptive wake, and still others will more slowly arise as ever newer tech and processes are created and deployed. We need to be ready for all.

Some of these new jobs will spring up at us, others will quickly evolve directly out of the automation’s disruptive wake, and still others will more slowly arise as ever newer tech and processes are created and deployed. We need to be ready for all.