Part Four: China’s Robot Reply

Will foreign robot suppliers dominate China's million-plus factories?

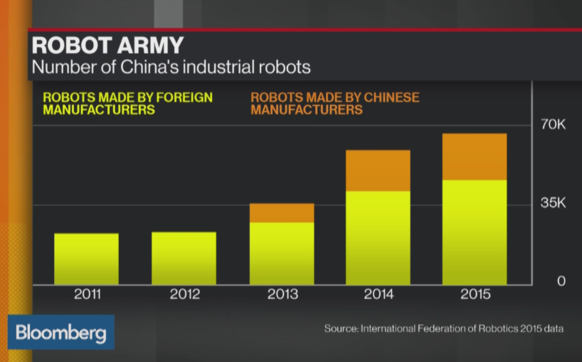

“About 70 percent of robots used in China are produced by global brands.”

—Chiang Chia-wei senior analyst Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC)

Will “Made in China 2025” devolve into “Made in China—by foreigners!—2025”?

Very wealthy yet very vulnerable

As the Nikkei Asian Review puts it, China is on an industrial robot buying spreeand will be for the next four years. Monthly, between 8,000 and 13,000 steel-collar workers arrive either by the boatload to ports along China’s east coast or march out of robot plants in China (Macquarie Research; International Federation of Robotics).

Those are astounding numbers.

See: Part Three: Robot Parts: Critical Importance Amid Explosive Growth

Even more mind boggling is where they’re all headed. Destinations for most are into the vastness of China’s universe of factories, which number 1.9 million, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. There’s not a country or continent in the world that can even come close to that number.

For a little perspective, the National Association of Manufacturers puts the U.S. factory total at a little over 250,000. China’s nearly 2 million factories is like every resident of Vienna, Austria, having his or her own personal factory.

This universe of factories, built mostly over the last thirty years, is what powered China to go from producing less than 3 percent of the world’s manufactured goods in 1990 to over 25 percent today. All of which matters because that universe of factories is what created and sustains the way of life that every Chinese citizen benefits from today.

This universe is getting an ambitious and hurried automation makeover, without which China will Humpty Dumpty.

Thousands of the factories will be razed or converted to warehouses, thousands more built anew, others will be gutted and renovated, and still tens of thousands more will merely swap out humans for machines. Whatever the final census, the universe will still be the biggest ever built.

This automation makeover seems to be for all the right reasons, as is the buying spree, as is the haste at which it is being carried out.

See related: China Races to the Factory of the Future

However, for all of China’s staggering wealth, power and influence on global trade, it is ever more vulnerable to foreigners supplying it with industrial robots, and more importantly, the parts and new advances in technology necessary to keep China Inc., and by extension, Asia Inc., humming along.

China is aiming at an annual output of 100,000 industrial robots by 2020,according to a plan issued in April 2016 by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. China is racing to close the “robot gap”, without which the much heralded “Made in China 2025” will devolve into “Made in China—by foreigners!—2025”.

For China, that’s a dangerous place to be.

China’s dilemma

Although China has big stacks of chips to play with, it’s not holding many good cards when it comes to industrial robots, a few trump cards are very necessary if you’ve got a yen for high-end manufacturing and a million-plus factories to modernize.

Georg Stieler’s reporting in Industrial Robots in China 2020 shows China gaining some ground in establishing its own indigenous robot manufacturing industry, as well as sales: “The seven leading domestic manufacturers grew 10 percent faster than the seven leading international manufacturers last year [2016].”

Stieler agrees with most Chinese forecasts that China’s homegrown robots will secure 45 percent of sales by 2025 (up from 16 percent in 2015).

With the cost of an imported industrial robot (including application-specific peripherals) between $65,000 to $145,000 per machine, a 45 percent domestic share of 8,000 robots a month represents a colossal savings.

Okay, that’s progress, but Stieler points to a big caveat: Chinese manufacturers are not making the 6- to 7-axis robots necessary for sophisticated manufacturing, which is the direction in which China needs to go. Instead, domestic factories are putting out 3- to 4-axis robots. Commendable, yet short of the true goal.

Li Zheng, Current Situation and Future of Chinese Industrial Robot Development, argues that such sophistication is emerging, but China’s robot industry is still very young. It’s only been since the 1990s with the National 863 Plan that any emphasis was put on developing industrial robots, and a good ten years on from that until the formation of “robot industrialization bases” and R&D facilities.

Who then, nearly a decade on, should be held responsible for the fact thatChina holds less than one percent of industrial robot patents and has a very limited pool of robotics professionals. “Presently, very few in China can independently design and program industrial robots. Control systems and programming software mostly depend on importation.” Not to mention that there is also a robot technician shortage.

So how does China pursue robot-driven automation for a million-plus factories while, simultaneously, quickly exiting from the danger zone of total dependence on foreign robotics technology? Moreover, how to pull off such an escape when China hasn’t done much about escaping anything in robotics for a decade or more?

Critical to robot-driven automation is how to sustain it over time. How will China’s universe of factories eventually evolve from Factory 4.0 to Factory 5.0? From “smart factories” to “AI factories”?

Whether common 4-axis or fancy 7-axis robots churning away in China’s universe of factories, they all have a common need without which the universe will grind to a halt. Regular maintenance and replacement parts—about which China is even more vulnerable than it is with manufacturing the robots themselves.

Japan, The Emperor of All Robots, has put together and is rapidly executing a masterful plan to be the go-to supplier for all robot parts anywhere in Asia.Total parts availability of high-quality products, guaranteed delivery, and peace of mind, is the offer. And yes, pricey, sometimes very pricey, is the cost of doing business, but the alternative is unthinkable.

See related:Eyeing China, Japan Ramps Up Robot Production

China’s bold reply

China’s reply to the widening robot gap is simple and bold: Spend. Spend a lot, spend it wisely, and spend it fast. Most importantly, spend to leap ahead. Spend to ensure technological advancement.

Part One:Robot Blast Off: China Spends Its Way to Victory

Sure, in the long run it also wants to nurture a homegrown robotics champion to be its lead robot developer. Siasun Robot & Automation (founded in 2000) is that champion.

And sure again, it also wants to see homegrown automation manufacturers commit to developing robots. Estun Automation (founded in 1993, but a robot builder only since 2011), is a perfect example. Having sold its first robot in 2013, and manufacturing only 1,000 per year, Estun is about to up its game with a new plant (the size of three football fields) in the Jiangning High-Tech Zone in Nanjing.

According to Jack Wang, Estun’s chief engineer, output is scheduled to be 15,000 robots annually plus speed reducers, drives and control devices, and servomotors.

Qu Xianming, an expert with the National Manufacturing Strategy Advisory Committee, which advises the government on plans to upgrade the manufacturing sector says that China aims to break foreign dominance in the manufacture of core robot components in one to two years.

“We aim to increase the market share of homegrown servomotors, speed reducers and control panels in China to over 30 percent by 2018 or 2019,” said Qu. If in two years China will be at 30 percent, how far back are they here in 2017? Way back and way vulnerable is where China is at this moment.

Today, delays in achieving market share in parts costs China tens of millions of dollars; in the future, with hundreds of thousands of factories all populated with robots, lack of significant market share in critical parts could mean disaster.

By way of reference, a speed reducer for a high quality FANUC M900iA/350 robot, retails for $13,852; do the math for tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of just this one, foreign-made part. Staggering!

In addition, swapping out parts is not yet done by other robots; humans do it. As Gerald Van Hoy, a senior research analyst at IT research firm Gartner explains it: “China currently has a problem sustaining the robots it has already installed. When a robot breaks down or malfunctions it stops the line until someone qualified to work on the robot arrives. This can take a while, particularly in western China where infrastructure may be an issue.”

“This is not to mention that there is also a shortage of trained personnel to operate and maintain such advanced machines. It takes time, even in a crash-course approach, to get enough intelligent people into those positions.”

It’s good to remember here how many new robots are disembarking at China’s ports and how many are marching out of factories each month, and how the situation that Van Hoy describes is getting exacerbated with each passing month.

How do we get to tomorrow?

The trip from Midea’s headquarters in Shunde to the home office of Yaskawa in Kitakyushu must have been an anxious one for the Midea execs. Some may even have smiled at how sweet it would be to have Yaskawa robots lifting and heaving Midea microwaves, stoves, refrigerators, and air conditioners at its 21 production facilities and 260 logistics centers.

They were off to Japan to make an offer to acquire Yaskawa, which at 300,000 machines is the second largest installed base of robots in the world. The guys from Midea were aiming high. China was being bold.

If they could score Yaskawa with its production capability, expertise, and patents, it would be a great coup not only for Midea but also for China. China wouldn’t have to wait to nurture a domestic robot company to the top tier; it would instantly own one of the world’s best.

The offer was politely rebuffed by Yaskawa. It is probably safe to say that theEmperor of All Robots breathed a sigh of relief as the guys from Midea boarded a plane bound for Augsburg, Germany.

The big orange KUKA logo dominates the building at 140 Zugspitzstraße. Looking up at KUKA headquarters from the sidewalk, the Midea team already owned 13 percent of the world’s fourth largest robot company. Just maybe, KUKA could be persuaded to sell them the rest? After all, Till Reuter, KUKA’s current CEO, began his takeover of the company in 2008 with barely a 5 percent stake.

August 2017