Part Two: The Guru of Shanghai

Forecast for Industrial Robots Through 2020

Georg Stieler’s purview on robot automation after six years in China

The guru speaks

He’s German, we’ve anointed him with the Sanskrit title of guru, and he eats, drinks and sleeps robots in China’s high-tech hotbed, Shanghai (population 29 million). It’s a big place with big things going on, and offers a perfect perch for a wide perspective on the biggest story around: Asia’s industrial revolution.

Six years ago, when Georg Stieler peddled his mountain bike down The Street of Eternal Happiness in Shanghai, there were few if any like it anywhere in town. Six years on, there are thousands of mountain bikes, plus scores of riding clubs, all rubbing handlebars together in a place gone crazy over bike sharing with Mobike’s 450,000 two-wheelers.

Stieler Technologie & Marketing Beratung, Lörrach, Germany, had a hunch that industrial consulting and business development might thrive in China, so Georg was dispatched in 2011 to set up shop on Zun Yi Road.

Turns out, nice hunch.

Georg and his Stieler Technologie crew scour factories and warehouses all over China, and turn them into tight, exhaustive and very valuable research reports and forecasts on the state of machinery, logistics, automation, and investments in the People’s Republic, and what the People’s Republic is doing with technology abroad. For example, Trend report: Industrial Robots in China 2020.

Quick to read the handwriting on the wall, Georg has now included India in the Stieler purview of Asian technology: Mobile Working Machines India (MWMI).

Good friend and robot automation buddy, Georg is always open to sharing some of his Stieler robot wisdom with Asian Robotics Review. In June, he favored us with a bit of that treasure in answering a few questions that we put to him.

Q: Foreign manufacturers are still responsible for the vast majority of robot sales in China. In 2013, China claimed that sales of domestic industrial robots were about 16 percent of the total and has been growing since. The government projected that indigenous Chinese robot makers would have 45 percent of China’s industrial robot market by 2025. Is that realistic?

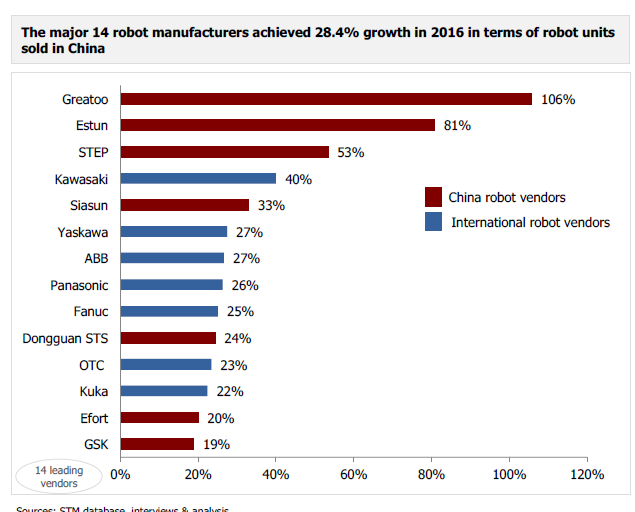

A: Yes. The seven leading domestic manufacturers (see chart) grew 10 percent faster than the seven leading international manufacturers last year [2016]. Eight years [until 2025] is still a ways to go. However, during this time, domestic manufacturers will gain further know-how from Chinese employees who leave international competitors and also through further takeovers. From my perspective, the 45 percent is a realistic goal…which might even be surpassed.

Q: Just two years ago, Japanese robot manufacturers were worried about declining purchases of their robot products in China. As of 2017, that seems to have reversed. More and more, especially FANUC and Yaskawa, I see Japanese/Chinese partnerships flourishing again. What’s your understanding of the situation?

A: Not only FANUC or Yaskawa, which declared to deepen its partnership with Midea in the field of robots for elderly care, and then just recently announced another partnership with another local Chinese company for the production of industrial robots. In fact, Kawasaki was the foreign robot manufacturer with the strongest growth in 2016.

There is a certain mistrust between China and Japan, also between China and South Korea – to put it mildly. As long as there are no suitable domestic offerings and Japanese robots are more economical than German or Swedish robots, Chinese entrepreneurs will keep buying them.

Q: China manufacturers over 70 per cent of the world’s production of computers, communication equipment and consumer electronics, which need unique competencies for complex production solutions.

The 70 percent is a big number. I would imagine that China will try to get one or more of its indigenous robot manufacturers to develop robot(s) capable of intricate assembly work. Are there any Chinese robot manufacturers even close to developing such a specialized robot?

A: What we are seeing is that electronics contract manufacturing companies such as Foxconn are still hesitating when it comes to deploy collaborative robots at a large scale. Most of the so-called Foxbots are in fact handling equipment with 2-3 axes.

For products with short life-cycles such as the iPhone, it is still easier and more cost-efficient to train human laborers than to automate the production completely. But it will change gradually over the next years with the availability of cheaper collaborative robots.

Q: “Over 80 percent of the robots in the Chinese market are sold through system integrators.” In the West, system integrators are under pressure as robot manufacturers jump them to go direct to the customer. Is that a possibility in China or does the government intervene on behalf of integrators? Obviously, as it is in the West, customers can save a lot of money by going direct while robot manufacturers can as well

A: Also in China, robot manufacturers are trying to get a bigger share of the integration market. However, in particular, the international suppliers often do not offer the most affordable solutions. They are not interested in projects where only small batches of robots are being sold. There are still a lot low-hanging fruit in the market: simple loading and unloading applications, where domestic robot manufacturers and system integrators are trying to underbid each other.

In our analysis of the M&A behaviour, we saw that vertical integration is certainly the dominant phenomenon. There is a trend to buy system integrators for better market access and application knowledge in particular (even the valuations are already high, since many listed companies also bought robot companies to provide some phantasy for their share prices in the first place).

A lack of integration knowledge is a threat for robot manufacturers. In fact, we see this as the more important driver for their engagement in the system integration business than short-term profits from projects in the field.

Q: Speaking of indigenous robot manufacturers in China, I have seen a few Chinese-made cobots (similar to Universal’s UR line) and AGVs, but not many, and certainly not enough to meet the country’s needs. What’s the state of Chinese-made cobots and AGVs look like today and is there a movement to increase their numbers?

A: Besides prototypes for collaborative robots from established robot manufacturers such as Siasun, we see a couple of promising initiatives in the field of collaborative robots – AUBO, Han’s Motor, Elephant to name just a few. Easy operability is key, some even experiment with machine learning and machine vision. Most of them are in a price range between $10,000 and $15,000 . Once these products are available to the market, this will lead to a wider distribution of cobots and put pressure on companies such as Universal Robots or Rethink Robotics.

The market for AGVs is already dominated by domestic companies. They are responsible for ~80 percent of sales. China still spends 10 percent more of its GDP for logistics than developed countries such as Germany and the US. The modernization of classical manufacturing sectors such as automotive, 3C and tobacco generate strong demand for automated logistic solutions. Also, mobile commerce is booming. Besides established players in AGVs, China’s large e-Commerce companies are entering this field: Alibaba through an investment in Geek+ this April, and JD.com with its own robotics department comparable to Amazon’s strategy.

Q: Parts, parts, parts! My understanding is that China buys robot parts at exorbitant prices (especially indigenous robot manufacturers). How close is China to creating domestic suppliers of robot parts?

A: The high purchasing prices result from comparably low sales volumes of domestic manufacturers, when compared to their established foreign counterparts.

Being able to manufacture controllers, servo systems and precision gears for robots is a part of Beijing’s Made in China 2025 strategy. We see six domestic reducer vendors in test trials at leading robot manufacturers. Some of them are being used due to political influence. Others, such as QCMT are trying to get ahead with the foreign help (smart manufacturing pilot project with Bosch).

As we have seen in other fields, such as machine tools, political will cannot make up for diligent engineering. Overcoming cultural issues requires time. Generous subsidies sometimes cause the opposite of what was intended and make things even worse. On the other hand, domestic robot manufacturers see their disadvantages and are trying to overcome them. Not to forget the aggressive outbound M&A – if you can’t make it by yourself, buy the company (as Midea did with KUKA , and more recently the acquisition of Servotronix ). We should be prepared for surprises.

Tom Green

July 2017