Can Asia leapfrog to innovation leadership?

Goodbye, Shanzhai: The Future of Innovation in Asia

Industrial innovation: Out of labs and onto the factory floor

“If you wander around in factories around the world, you see some very sophisticated knowledge work…They’re extremely sophisticated and complex, and a lot of engineering goes on “on” the factory floor.” –Willy Shih, Harvard Business School

Meeting the innovation imperative

That labor costs are skyrocketing in China is a good thing for China. That rapidly ageing workforces are crashing the future outlook for manufacturing in Korea and Japan are good things for Korea and Japan.

Labor costs and ageing workforces are driving technological advancement in Asia; advancement that is desperately needed for a host of far more important reasons other than labor costs and ageing.

Oxford University and CitiBank, authors ofThe Future Is Not What It Used to Be, argue that wage pressure on Asia, especially China, is a “a silver lining” for the country, because it was exactly wage pressure that influenced the first industrial revolution in the 18th century.

For Asia, on the cusp of being the first to actively confront the Fourth Industrial Revolution, such comparisons bode well:

“We are at the beginning of a revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope and complexity, what I [Klaus Schwab, founder, World Economic Forum] consider to be the fourth industrial revolution is unlike anything humankind has experienced before.”

Context-aware technology

Asia—beginning first in China, Korea and Japan before heading south—is being presented with an opportunity to leapfrog its manufacturing industries out from under the rap of shanzhai or “copycat technology” to an unprecedented leadership role in global industrial automation.

It’s a fast-approaching age where smart factories will replace laboratories as hubs of innovation. New tech inventions as well as process improvements will derive from the machines themselves during the course of manufacturing.

As Asia leapfrogs the laboratory for the factory floor, it will gain an edge in innovation, the speed of innovation, patents and other intellectual property, and the speed of technology transfer from innovation to real-world practice.

In short, the factory floor will become the laboratory; the factory floor will become better than the laboratory ever was.

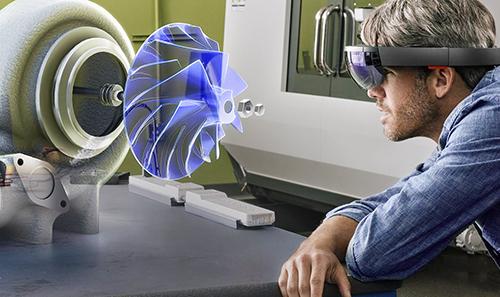

Imagine a machine telling its operator that one of its parts is about to malfunction. That’s what’s called context-aware technology: a machine or other asset offering up data on its operation as well as its relationship to other machines or assets.

Imagine the operator wondering why the part is imminent to failure and how it could be corrected—not by just switching the part out for a replacement—but actually analyzing the data—the steps to failure—and then innovating a better part because of that analysis. That’s innovation!

Now imagine getting even smarter by going from 3D to 4D modeling tech, allowing the operator to toggle back through time to understand the point at which the part first began its journey to failure.

The factory is suddenly a laboratory!

Asia is now faced with an opportunity to leapfrog from laboratories to smart factories operating context-aware technology—at scale!

China, for instance, as it switches out tens of thousands of workers for tens of thousands of robots across entire industries, has enough spring in its manufacturing legs to make a quantum leap in industrial innovation; a leap that may not soon be equaled anywhere in the West.

Such an opportunity would align with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s quest to catch up with the West in everything from aircraft engines to quantum teleportation. The state Xinhua news agency lists brain science, deep space, smart manufacturing and robotics as other of his key goals.

McKinsey has labeled China more of an “innovation sponge” than a true innovator, “absorbing and adapting technology, best practices and knowledge from overseas.” What in China has come to be known as “Shanzhai” or copycat technology.

In Asia, copying is a tried-and-true legacy means of uplifting a country; it’s only in the West that it’s gained such a pejorative connotation. Both Korea and Japan took it as a “golden wind” of economic opportunity. In and of itself, it’s a kind of leapfrogging.

East to West “copying” was foundational to the First Industrial Revolution. Arnold Pacey’s Technology in World Civilizationtraces the line of descent of Chinese silk looms to Italy and then to the Netherlands and then as progenitors of Arkwright’s looms in Derbyshire.

In short, that’s how technology gets around, and always has. Technology travels, gets adopted, gets adapted, improves, and the improvement moves on yet again.

Asia’s leapfrogging from its less than efficient telephone landlines to cell phones was a huge economic windfall. Asia went on to improve cell phones and then reintroduced them back to the West. Japanese high school girls were the drivers for the installation of the first cell phone with a camera. And look where “selfies” and YouTube videos have brought us ever since.

What took the West two hundred years to accomplish, Asia did in less than fifty, is how Singapore’s late leader Lee Kuan Yew saw it. Being an “innovation sponge” played an important role in that time compression.

Korea and Japan are mature economies with decades of experience in turning themselves into domestic innovation engines with thousands of homegrown technology products.

China, on the other hand, although it acts like and is an economic behemoth, is still an emerging country with a per capita GDP lower than that of Bulgaria, Botswana and Mexico. Then too, unlike the economic rise of Korea and Japan, China lacks time; it doesn’t have decades of a “golden wind” at its back.

However, being late to the party seems to present China with an advantage: lack of an established high-tech manufacturing infrastructure may well be a boon when trying to leap from laboratory-oriented innovation to innovation derived from a smart factory with context-aware technology.

“Asia’s business landscape is poised not only to benefit greatly from AI’s rise, but to also define it,” reports MIT’s Technology Review

China, unlike its East Asian rivals, Japan and Korea, has a job of epic proportions ahead of it, if it’s to take advantage of smart factory innovation. Tens of thousands of China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) will need to be retrofitted to meet the new opportunity plus thousands of new factories need to be constructed.

The end game for all three of these nations is to firmly establish persistent innovation consistent over time, a goal which will not be realized through copying or being a technology sponge. The smart factory with context-aware technology, especially robot-driven automation, is the only way out.

Business as usual for China won’t cut it any longer. As the Financial Timespoints out:

“China needs to boost productivity if it is to escape the ‘middle income trap’ where a low-wage manufacturing economy fails to make the leap to one based on invention and technology.

“However, multi factor productivity, a broad proxy for innovation, is actually declining, accounting for just 30 percent of GDP growth in the past five years — a fall from 40-48 percent in 1990-2010, according to McKinsey.”

Getting there will be a tough slog

With smart factories, the old concept of manufacturing, is slowly dying off and will eventually get replaced with a new reality of data and analytics supporting manufacturing from the very beginning of a product’s lifecycle.

And with smart manufacturing, the U.S. Department of Commerce sees $371 billion in net global value over the next four years.

A decided aid in that cause: “The explosion of low-cost sensor technologieshas made nearly every manufacturing process and component a potential data source. Innovative manufacturers can use the resulting data sets to gain insights about the physical fabrication process, improving efficiency, increasing yields, and reducing product defects.”

Harvard Business School’s Willy Shih, professor of management practice, who also spent twenty-eight years in industry, is a keen observer of factories and what they’re all about. It’s no longer a place where four screws are put in 2,400 times a day, he says wryly.

“If you wander around in factories around the world, you see some very sophisticated knowledge work…They’re extremely sophisticated and complex, and a lot of engineering goes on “on” the factory floor. For some types of manufacturing, it is very important to maintain production capability because it’s tied to your ability to innovate.”

China’s leadership fully realizes the task at hand. When in 2014, “President Xi called for a “robot revolution” that would transform first China, and then the world, he told the Chinese Academy of Sciences: “Our country will be the biggest market for robots, but can our technology and manufacturing capacity cope with the competition?”

Here in 2017, President Xi is still looking to answer the same question, but to its credit, China has now begun in earnest with the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) to try to put substance to seeking out the answer to “can our technology and manufacturing capacity cope with the competition?”

Brian Carpizo, a consultant with Chicago-based Uptake Technologies, sees the looming Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) as the grand prize behind the future of manufacturing: “I’m focused on industrial insight in manufacturing enabled by IoT. Innovations in hardware, big data, connectivity, analytics, and machine learning areconverging to create massive value-creation opportunities.”

If Asia can leapfrog from lab to smart manufacturing, it will be well on the way to meeting up with that IIoT convergence further down the road of transform-ation. Lots still need to be done to get to an IIoT state of manufacturing in general, but the realization of the smart factory and context-aware technology is a quantum leap in that direction.

Japan’s challenge

In 2015, Japan ramped up its own transformation to smart factories, calling it theIndustrial Value Chain Initiative.

However, that may well be easier said than done, according to the Nikkei Asian Review’s Japanese companies not yet prepared for next tech wave.

“With its proud history of technology and innovation, Japan seems well positioned to lead on this new path [Industrial Value Chain Initiative].

“On a closer look, however, things are less certain. The internet economy’s concepts of service and ecosystems are alien to Japanese manufacturers, steeped in their success during the Third Industrial Revolution. The problem for Japan is not technology, but mindset.”

That’s ominous sounding, but given the stasis and lethargy of Japan’s economy over the last decade, Japan’s transformational capabilities may be similarly lethargic.

The Nikkei commentary further explains: “Japan’s record in services transformation is dismal. The country is well known for its single-mindedmonozukuri craftsmanship culture of building near-perfect hardware. But this linear thinking makes it difficult to adjust to a customer-centric model that emphasizes software and services.”

If true, that speaks more to a lack of awareness or national will than to Japan’s technological skill set or vaunted manufacturing prowess. Journeying then to a position of smart factories and context-aware technology may well be a good way station on the learning curve toward the Industrial Value Chain Initiative[and/or IIoT].

As Carpizo points out: “We’re still in the early stages of IoT in manufacturing so there are definitely opportunities to obtain first-mover advantages…Data integration and system interoperability is the first challenge. There are a lot of systems and machines producing data but very few ways to exchange and store information in the standardized way required for adoption of IoT solutions at scale.”

Japan, it seems, has time on its side, but not much.

See related: Emperor of All Robots Put to the Test

Korea’s challenge is more difficult

Korea has a lot more pieces of a manufacturing solution to put together than Japan, but fewer than China (Korea’s main trading partner).

In its Smart Industry in Korea, the Dutch government’s Jeong Eun Ha, Officer for Innovation, Technology & Science (Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland), reports:

“Korea has one of the leading manufacturing ecosystem and IT infrastructure, but they are weak in obtaining core technologies for a smart factory such as sensors, Internet of Things (IoT) and hologram.

“In addition, Korea is facing difficulties designing computer programs and other software solutions. Therefore, the Korean government has initiated a project called “Innovation in manufacturing industry 3.0” in order to create new value and obtain competitiveness in manufacturing sectors by converging factory and IT to accelerate the smart factory system. By doing so, it is expected to pave the way for the reform of the manufacturing sector.”

See related: Korea Awakens, Reacts…and Accelerates

Advantage Asia…for a time

All three of the East Asian giants, although far from their smart factory/context-aware technology goals, are very aware of the challenges set before them and are well on the road to their respective high-tech way stations.

They are actively confronting the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which is heads and shoulders above what the West is doing.

The West, of course, will come roaring up sooner than later and will equal or exceed Asia’s gains. At that point, the IIoT movement will have taken on global scale, which it needs to do to be truly effective.

In the wake of all the putting forth to push smart factory transformation and context-aware technology onto the world stage, a new age of Asian innovation will have sprung up; taking place first in East Asia before moving downstream into Southeast Asia.

It will be persistent innovation that’s consistent over time, and it will have leapfrogged from laboratories to a more natural breeding ground on the factory floor. And it won’t be just resident in Asia, it will be everywhere.

See related: Blast Off article series