New-Age Tech Partnering

Steel-Collar Farmhands: Robots in Fields & Orchards

Accelerating innovation and speed to market via partnerships powered by investments from industry titans John Deere, Kubota, and Yamaha. Is it the new normal for field robotics?

Forecasters like what they see: Global markets projected to jump

from $7.4B in 2020 to $20.6B by 2025. That’s a whopping CAGR of 22.8%!

Tom Green

Innovation on the farm

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, McCormick’s reaper, Ford’s farm tractor, agriculture has been acquiring labor-saving devices since human’s first went from being hunter-gatherers to land-tilling food growers and livestock raisers.

The work is hard, the hours long, the weather’s fickle, the harvest is a do-or-die must, so why wouldn’t any right-thinking human brain want to conjure up a few new ways to lessen the load?

And that’s just what has happened for millennia. Today, robots and other autonomous machines prowling fields and orchards are just the newest incarnations in farming’s eternal quest for ease of doing business with Mother Earth.

And the “land-tilling and livestock raising” that humans created for themselves, they have been trying to wiggle their way out of for hundreds of years. Who wants the grief of farming when gleaming cityscapes beckon and the allure of industry and business are so damn attractive? Even the meatpacking, city misery of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle offered a slim chance of escape to a better life.

Not so farm life, it’s forever, unless you get conscripted into someone’s army or a machine comes along and makes your work redundant, which is exactly what has happened.

Farm workers don’t need their arms twisted to encourage fleeing the farm; they’ve been leaving by the millions never to return, except for holidays. Barely 1.5 percent of America’s population are farmers; in Germany it’s about 4 percent. China has over 400 million farm workers; ten years ago, China had 700 million. That’s an incredible 30 million a year making a dash for the cities.

But still, we all have to eat. Someone has to feed us. And the global appetite is on the grow…exponentially:

“The human population is expected to climb to 9.8 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100, according to the United Nations. To feed the world — with less land, fewer resources and in the face of climate change — farmers will need to augment their technological intelligence.” —NYT: A Growing Presence on the Farm: Robots

See related: Feeding Asia: Robots, Automation & Four+ Billion Mouths to Feed

From farm to chopsticks: Not enough land, not enough water, too few farmers, and $470 billion in annual food spoilage

Steel-collar farmhands

Erik Pekkeriet of Wageningen University & Research predicts that “10 to 20 years from now, robots will do all the repetitive work in the agricultural sector.”

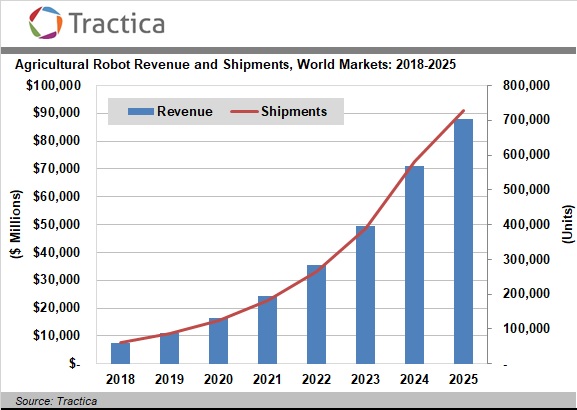

Maybe sooner. Research forecasters are reporting “agricultural robots to develop rapidly (2020-2025)” topping out in 2025 at $20 billion. Amazing, especially so since the market was only $3.4 billion in 2018.

Maybe that’s what is generating all the recent media buzz on robot farming. To nearly triple growth is definitely eye-popping. Something is definitely going on

Tractica has even produced a chart showing the coming inflection point: 2021 looks like the jump-off point for agricultural robot shipments to drastically increase (see chart).

So, what’s happening?

David Frabotta, writing in PrecisionAG, has what looks like the most sound take on robots in agriculture with his article: Agricultural Robotics Segment Maturing Amid Intermittent Commercialization. Perfect title!

Isn’t this what we’re seeing: “In agriculture, technology introductions have sputtered for numerous reasons: A prolonged global recession dating back to 2008 slowed investment, lack of interoperability standards created disparate ecosystems, and products focused too much on the technology instead of addressing real-world grower problems and workflows.

“But those dynamics are changing for the better, and real change is starting to creep into the market as leading companies are on the cusp of changing the trajectory of innovation and adoption.

“Here’s why: Partnerships and collaboration among leading companies are accelerating innovation and speed to market. Start-up culture historically has been a lonely endeavor as inventor companies cautiously guard proprietary advancements amid competition from inside and outside of agriculture.

“But that is changing for a couple reasons, primarily because technical and operational challenges are too complex for any one company to create a complete platform. Robotics, which implies autonomy, requires sophisticated mechanization and software. Mechanization requires a supply chain, and software requires interfaces for interoperability. Many companies have tried to create a ground-up platform internally, but the complexity has rendered this approach unfeasible.

“It shows a great deal of business maturation for start-ups to seek partnerships and joint ventures to accelerate product life cycles and commercialization, and that business maturity will help garner more investment.”

Echoing Frabotta’s complexity issues for field robots and the need for partnerships are a spate of articles popping up with increasing frequency like this one in Future Farming: Field robot market lacks direction and collaboration.

As the writer aptly points out: “Development of field robots is a lengthy process. The list of robotics projects that never or have not yet made it into practice is long. As soon as the innovation grants are used up, the free market proves extremely tough. For a start-up without equity, there is nothing in sight but the financial chasm.

In the meantime, crop farmers are very skeptical in view of the coming and going of robot manufacturers.

Tijmen Bakker, a PhD in field robotics for ten years, understands that the tech from the outside may appear to have been stagnant for the last decade. Chief among farmer misgivings is that with automated systems “there is no driver’s insight regarding assessment of the output produced by the tool. The tractor driver is aware of many things simultaneously that are difficult to define for a robot.” However, insiders know, he says, lots of the requisite technology has improved greatly over that time.

The key technology that he thinks will push field robotics over the hump is artificial intelligence: “If tools soon become intelligent and the safety issue is resolved thanks to deep learning, it will make little difference whether the tools are attached behind a robot platform or an autonomous tractor. I expect to see rapid progress over the next few years.”

Will partnering become the new norm?

Tractor manufacturers have taken note and are moving in as field robotics quickens with viable and near-viable products for the market. John Deere and Kubota, both deep-pocketed power players in agriculture have made significant moves lately. Deere acquired (2017 for $305 million) Sunnyvale, Calif.-based Blue River Technology, a developer of autonomous crop-spraying equipment that relies on machine learning.

Kubota recently invested (what nippon.com calls “several hundred million yen”) for an apple-picking orchard robot from Abundant Robotics Inc., Hayward, CA. With the State of Washington harvesting 5 billion apples annually—all picked by hand by a rapidly diminishing labor supply—Abundant could have the killer app for all hanging fruit. Kubota’s acquisition of Kansas-based Great Plains Manufacturing, Inc. (2016 $430 million) with its agricultural implements for tillage, seeding, and planting applications like finish mowers, rotary tillers and cutters, landscape-seeding equipment, zero-turn mowers, and dirt-working implements, is a lineup of farm implements ready for automation, or pulled around by Kubota’s new, space-age looking, fully-autonomous EV Dream Tractor (officially, AgriRobo tractors).

Yamaha jumped in with an investment in the T-6 strawberry-picking field robot from Advanced Farm Technologies, Davis, CA (2019 $7.5 million).

These full-line companies have the capital, dealer network, and deep R&D resources to vet worthy field robots and convince farmers to buy them. Other manufacturers recognize the maturity and capability of the tech, including key developments in sensors and software, and beginning to enter the fray as well.

VCs have been on the prowl in the space as early as 2012, investing, according to AgFunder, some $4 billion in farm robotics and mechanization.

Farm history keeps repeating itself through technology

In 1900 about a third of America’s population lived on farms; today, less than two percent. Mechanization brought tractors and combine harvesters that automated the manual labor formerly done by small armies of threshers and bundlers. Today, if one can muster up the hard-to-find picking and field labor, such armies represent 40 percent of a farm’s overhead.

Cyrus McCormick labored six weeks in his father’s blacksmith shop to produce his first reaper (his father had given up the attempt after years of trying). It sparked a revolution in agriculture. Previously, a skilled farmer at swinging a scythe could harvest two acres of grain in a day. With a reaper, one man with a horse could harvest large fields in a day.

With the help of deep-pocketed industry titans, modern-day McCormicks are in their labs carrying on the same revolution. They’re rolling out “reapers” for apples, strawberries, lettuce, and grapes, and farmers are finally liking what they see.

See related: Maybe we should call it Neo-Ag

Neo-Ag: Farming with Robots, AI & Ingenuity

A “Google moment” for agriculture that’s ultra-precise, data-driven, and brimming with special-purpose robots is also powering lots of new thinking