The Canary Stopped Singing

China’s Robot Industry Comes Alive

Homegrown industry threatens Japan's robot hegemony

which opens up a potentially unlimited market.”— Susanne Bieller, International Federation of Robotics (IFR)

The canary stopped singing

Back in the spring of 2017, when Japanese robot makers were feverishly shoveling billions of dollars in robot and robot part sales from China into their bank accounts in Tokyo, they wisely left behind a canary in the Chinese gold mine.

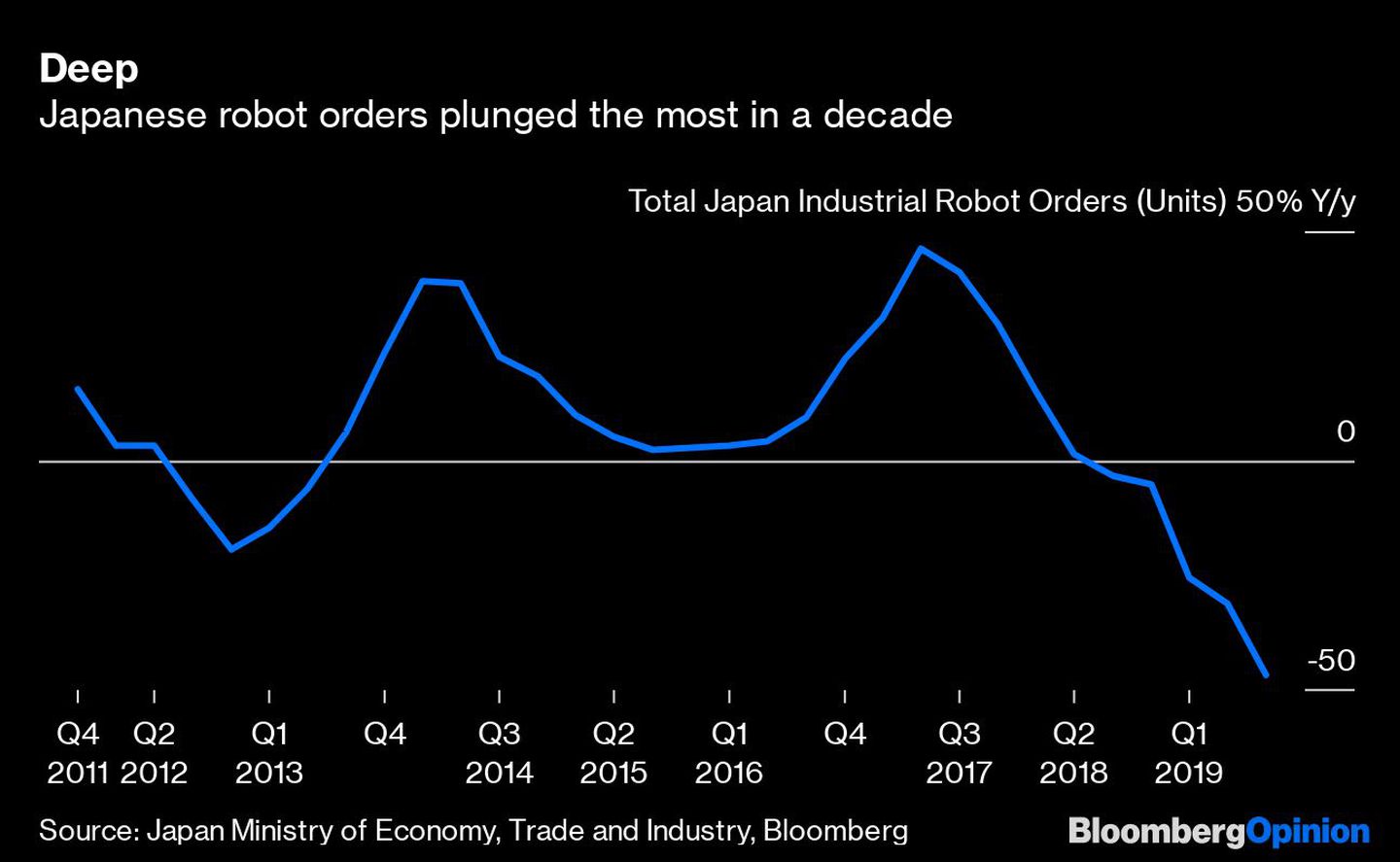

The canary wasn’t put there to warn against a dip in sales to China; most every Japanese robot maker is well aware of the cyclic rise and fall of robot sales over time (see chart).

The canary’s job was to raise alarm to something more important: Advance notice for when China’s domestic makers of industrial robots would begin to wiggle free from their not-ready-for-prime time chrysalis and assert themselves in the marketplace. All of which would herald a permanent downturn for Japan’s robot sales in China, which is a very big deal because one of every three industrial robots sold is sold to China. And most of those foreign robots are manufactured in Japan. “China is the largest importer of Japanese-made industrial robots, sucking in over a 40 percent share in 2018, according to Mizuho Research Institute.”

“China has been the top market for industrial robots since 2013—and it’s getting bigger,” writes Bloomberg’s Andre Tartar. “The country is currently on track to take delivery of 45 percent of all shipments between now and 2021, according to the International Federation of Robotics.”

These days the early-warning canary is in poor health, and not getting any better. Although foreign companies control over 60 percent of the Chinese market for industrial robots, their percentage is headed south, not north.

China’s robotics industry has now passed seven critical milestones:

- It crossed the 30 percent threshold of market share (43,600 units, up 16.2 percent year on year, with its recent showing of 32 percent of the total marketplace), well within striking distance of the targeted 50 percent by 2025 (although recently upped to a questionable 70 percent);

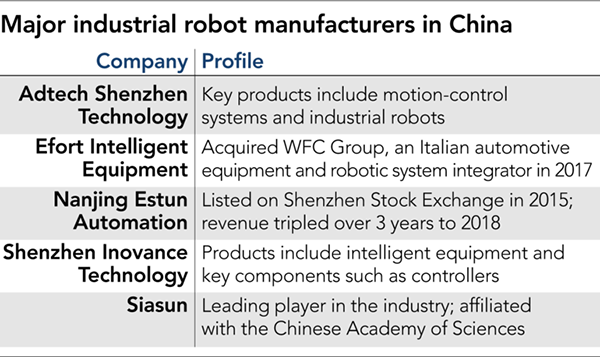

- Confidence from international buyers, with two-thirds of Siasun’s customers overseas, including General Motors, Ford, BMW, Jaguar and Land Rover;

- A fledgling but credible robot parts industry for both high-end and middle-market industrial robots (making 20 percent of key robot components);

- A burgeoning, high-quality industry of logistics robots (e.g. Geek+, etc.)

- Most notably, sales of foreign brand industrial robots manufactured in China were down nearly 11 percent year on year. For robot brand Japan, a Mizuho Research Institute sees this rate of decline as accelerating.

- Cobots, cobots, cobots! China sports a half dozen cobot makers, three of which have superb machines: AUBO, Elephant, and Han’s Elfin series. With China’s SMEs accounting for 90 percent of business entities in China, and 60 percent of the country’s GDP, cobots are forecast as $190 million business by 2020; and lastly,

- Overseas expansion via foreign direct investments (FDI): Siasun’s intention of investing in a 480-acre “smart” manufacturing facility for “systems integration and automation” in Thailand’s flagship Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

“We have bridged the gap with outside players in terms of quality and technology,” a Siasun executive said. “Siasun’s revenue jumped 26 percent in 2018.”

Siasun’s products are “on a par with those of Japanese and European manufacturers,” admits Kazuhiro Kosuge, a robotics professor at Tohoku University’s graduate school.

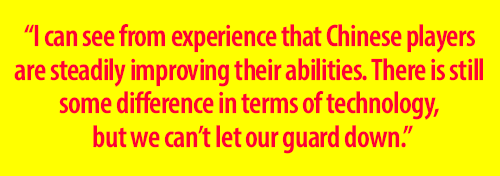

“I can see from experience that Chinese players are steadily improving their abilities,” said an executive at a key Japanese robot maker. “There is still some difference in terms of technology, but we can’t let our guard down.”

Yes, auto and cell phone manufacturing and assembly are ailing in China—usually mega-buyers of Japanese robots—but the cyclic dip this time around is sharper, deeper. Something else is at play. Overdependence on high-quality industrial robots for automotive makers seems to have backfired on suppliers like FANUC: “‘FANUC should expand the lineup of lower-priced products that meet bare-minimum quality requirements,’ said Tomohiko Sano at JPMorgan Securities Japan. ‘But compact robots for the service sector are a tough field with competition from Japanese peers like Nachi-Fujikoshi, Mitsubishi Electric and Denso. It is a field that is easy for Chinese companies to enter.’”

Susanne Bieller, general secretary of the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) agrees, adding: “Chinese suppliers are strong in exploring industry sectors beyond automotive and electronics, which opens up a potentially unlimited market, and makes the robotics industry less susceptible to any risks caused by weaker phases in single industries.”

Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have giant, unending government subsidies lavished on the homegrown robot industry with the aim of vaulting it into world-class prominence. If not for such subsidies, China would not have the most extensive and world’s best high-speed railway system. It doesn’t hurt technology to have friends in high places with lots of capital and a readiness to invest.

As Tartar concludes in his piece: “Yet, as the last few decades illustrate, China has regularly overcome deficits with wealthier nations by adeptly leveraging its immense scale and centralized political authority. The race to automate is unlikely to be any different.”

Still on the acquisition hunt

In an attempt to quickly bolster its technology chops, China has acquired over a dozen foreign robot manufacturers, the most notable being Germany’s KUKA for $5 billion in 2016.

However, when a market segment is targeted for acquisition, China is wasting little time and spares no expense on the overseas acquisition circuit. Welding was just such a market waiting for a full-bore acquisition hunt. Georg Stieler, an expert in Chinese robotics investments, reckons that “welding is 25 percent of the Chinese robotics market, behind loading and unloading applications at 44 percent.”

China has admirable robot welding startups, including the likes of Honyen, a Shanghai-based startup founded in 2014, and the country’s largest supplier of welding robots. “The company’s robots go for less than half the price of those made by foreign companies,” reported Shi Hongwei, Honyen’s vice president, to Nikkei Asian Review.

Still, China went shopping for more. In succession, Jiangsu Hagong Intelligent Robot Co Ltd. bought NIMAK (Germany) resistance welding, welding robots, gluing and dosing technology; Nanjing Estun Automation Technology Co. acquired Carl Cloos Schweißtechnik (Germany) robotic welding systems; and, as companion tech for welding and robotics in general, snapped up TriMotion (UK) motion control applications; MAI (Germany) manufacturing automation; and 20 percent of Euclid (Italy) 3D vision and robotics. Estun bought Cloos for $216 million, which is more than Estun’s total sales for 2018 of $203 million. Money, it appears, is absolutely no deterrent to China when it comes to acquiring automation technology.

But, as Stieler points out: “welding is 25 percent of the Chinese robotics market.” Something that big had to be addressed quickly and thoroughly, which China did in a hurry and to the max.

The spring of 2017

Asian Robotics Review’s 5-part series tracked The Blast Off in sales in the spring of 2017.

In those heady days, Yoji Ishimaru, president of the Japan Machine Tool Builders’ Association, enthused: “The bustle in China is lifting the whole market.” By April, machine tool orders from China had increased 2.4 times on the year to $278 million. Total orders in April exceeded the same period from the year before by 34.7 percent to $1.17 billion.

Japan’s robot exports to China had also taken off: $410 million in new shipments rolled out in the first three months of 2017, reported the Japan Robot Association.

Come 2019, just two years on, during a protracted Sino-American trade war, the canary stopped singing.

These days Japan’s industrial robot orders have fallen 47 percent—a decade low, while Japan’s machine tool orders fell 35 percent in the September quarter. The worst for both sectors since the 2009 financial crisis and global recession.

Learning from China

Ironically, China may be the place where Japan learns how to build better industrial robots. In Chongqing, known as “China’s Detroit”, Kawasaki Heavy Industries “recently opened a cutting-edge research center at its factory…to develop new uses for industrial robots powered by artificial intelligence,” a particularly strong suit of Chinese technology, while weak in Japan.

“Chongqing will become a top global market for robots, which are the keys to smart manufacturing,” said Yoshinori Kanehana, Kawasaki CEO, at the launch ceremony for the new research center.

In the near future, it could well come to pass that Japan—The Emperor of All Robots—takes home to Tokyo something more valuable than profits.

See related:

Why China Can’t Stop Spending Multi-Billions of Dollars on Robots, Cobots, Grippers, Robot Parts, and AVGs

Guarantees on $73 billion more in loans—while SMEs pick up $9.7 billion in government subsidies—to hurry automation through 2022.