Influence of Asian Industrial Robots on Manufacturing in North America

In 1983, there were 50 U.S. industrial robot builders, while in 2018 there are zero

Closer Look at Zero:

In Miamisburg, Ohio, Yaskawa Motoman “customizes” robots that are manufactured in Japan; while in Michigan, FANUC “assembles” robotsmanufactured in Japan. Also in Michigan, ABB, which “assembles” robots manufactured in Sweden and China, recently began “manufacturing” robots in Michigan (2017), having sold its first robot (an IRB 2600) to Hitachi Powdered Metals in Indiana. BTW: The Hitachi plant has 107 other ABB robots at work in Indiana, none of which were made in the U.S. Sami Atiya, president of ABB’s robotics and motion division, estimates that 75 percent of all robots delivered to North American users will be U.S. made by 2018. ABB may well have just started a smart robot trend similar to Japan’s automakers in Ohio in 1986.

Cause for alarm?

With this Wall Street Journal headline from March, Foreign Robots Invade American Factory Floors, there’s been some gnashing of teeth over America’s glaring weakness in making zero industrial robots.

Is zero important? Some voice a definite yes, others say no, a few look to AI as the great leveler of robot brands.

The stats are telling

Is it important that of the 34,606 industrial robots purchased by North American industries in 2016 (10 percent increase over 2015) that zero were made in North America?

Is it important that the $1.9 billion paid (another $516 million in 1Q2017) for those industrial robots is controlled by Tokyo, Zurich, and Beijing (formerly Augsburg)?

Is it important that the rush for automation going on in North American manufacturing is by and large totally dependent on Asian robots? In addition to mega-growth by U.S. industries, it’s been reported that “Canada saw a 49% increase in the demand for robotics, and Mexico grew by 119%” in 2016. So north and south of America’s borders industrial robot sales are booming as well.

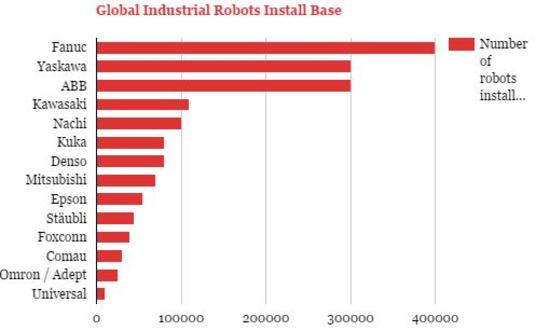

This chart shows who’s making all the robots. A definite tilt towards Asia

The global industrial robot market is “projected to reach $41 billion by 2020”, growing at a CAGR of 5.4 percent through 2020. Cobots are about 5 percent of total industrial robot sales in 2017; Barclays expects cobots to grow to $3 billion by 2020 and $12 billion by 2025.

By 2019, more than 1.4 million robots will be toiling away in the world’s factories. As robot-driven automation ramps up in North America is there the possibility that, say, an Elon Musk-type someone will pop onto the North America stage and start punching out industrial robots in Utah or Manitoba or Ciudad Juarez? Highly unlikely.

A more likely scenario might be for foreign industrial robot makers to follow the Japanese-car-making trajectory from the 1980s by locating robot factories in North America. ABB, the Swiss/Swedish robot builder, did just that in Auburn Hills, Michigan, and sold its first U.S.-made IRB 2600 this March. More foreign brands will certainly follow as automation transformation ramps up across North America.

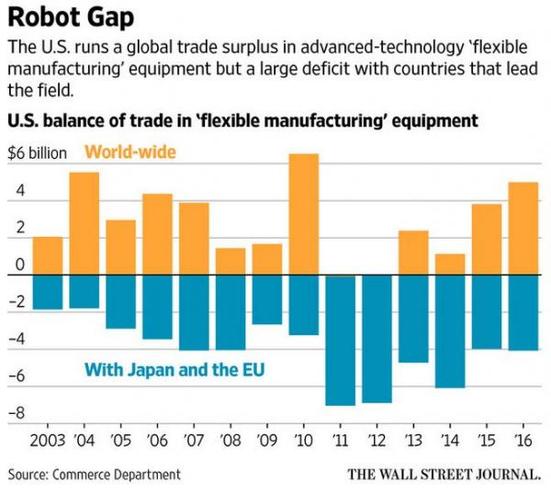

Of course, that’s not going to be enough to assuage the fears of some looking at Commerce Department data showing the U.S. last year ran atrade deficit of $4.1 billion in advanced “flexible manufacturing” goods with Japan, the European Union and Switzerland.

BTW: “flexible manufacturing” (FMS) refers to “cutting‐edge production machinery that is powering the new automated factory floor, from digital machine tools to complex packaging systems and robotic arms.”

The German VDMA (Mechanical Engineering Industry Association) reports that the U.S. provided nearly 80 percent of the country’s industrial machine needs until 1995, but by 2015 was producing only 63 percent.

Even the chart’s U.S. trade surplus, reports the Wall Street Journal, reflects exports of mainly “components and less sophisticated equipment.”

“If you want to build new production facilities in the U.S.,” says Torsten Gede, a manager at German investment group Deutsche Beteilgungs AG, “a large part of the machinery and technology has to be imported because local alternatives are rarely available.”

In 2012, President Barack Obama’s council of science advisers reported to him that the U.S. trailed “other rich nations on manufacturing innovation.”

That report eventually resulted in the 2014 Revitalize American Manufacturing and Innovation Act, which is basically a network (14 so far) of government research labs, universities and companies working to advance innovation in manufacturing. One such node in the network is the Advanced Robotics Manufacturing Innovation Hub hosted by Carnegie Mellon University.

Laudable as it is and extensive as the network appears to be, its $1 billion funding commitment from the U.S. government is plainly not near enough. By comparison, China’s Made in China 2025 initiative, which has a large research component, plus it’s Internet Plus plan, and its advanced manufacturing fund,have been seeded with well in excess of $6 billion, and that’s just for starters. Germany and Japan also outpace both U.S. and North American investments in advanced manufacturing.

Good old days are gone

Here in 2018, it’s hard to believe that the U.S. in 1983 could boast of having 50 native robotics manufacturers. That’s according to Competitive Position of U.S. Producers of Robotics in Domestic and World Markets (1983) put out by the United States International Trade Commission. Fifty! Early on, says the report, America’s robotics industry was on the rise…and beginning to surge.

The report also claims that the industry then suffered from three mortal blows: The recession of 1979-1982; “largely non-existent” government funding; and foreign imports aggressively jumping from $3.8 million in 1979 to $28.9 million in 1983.

To that sorry tale, the Wall Street Journal adds: “In the 1980s, as U.S. manufacturing slumped [the aforementioned recessions], almost seven of 10 American machine‐tool companies closed due to falling demand, the strong dollar and strategic miscues…The decline continued this century as U.S. manufacturers outsourced more and baby boomers retired. Shrunken manufacturers demanded fewer production experts, accelerating the factory‐technology decline.”

Shining star

North American logistics robots are a different story. With logistics robots—warehouse AGVs, order pickers, unloaders, shippers, and AS/RS systems (automated storage and retrieval), North America has a burgeoning industry that is a world leader. Robots and the Great Asian Warehouse Makeover reviews the dozen North American new kids on the block.

Since most warehouses and distribution centers worldwide are just beginning full-throttle automation, the potential for North American suppliers of logistics robots is at its peak. For example, China’s enormous white goods manufacturer Midea, the same Midea that bought Germany’s renowned robot builder KUKA for $5 billion, has 100 warehouses in 17 Chinese cities that are in great need of automation. The boon for KUKA and its subsidiary, Swisslog (logistics robots and AS/RS systems), is literally off the charts when contemplating the automation of 100 warehouses.

More foreign robots

North America, especially the U.S., can expect more foreign robots to arrive, and very soon.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s February trip to the U.S. strongly indicates a Japanese robot advantage. CNBC reported, “Japan is putting together a package it says could generate 700,000 U.S. jobs and help create a $450-billion market.” Automation and robots, especially on U.S. infrastructure projects, is a large part of the plan.

China, over a very short period of time, has developed seven indigenous industrial robot manufacturers. Siasun Robot & Automation is the most well-known. It’s not inconceivable that one or more of these seven, maybe Siasun itself, might be the one to build a robot plant in Utah, Manitoba, or Ciudad Juarez.

For some, it doesn’t matter who or what makes the robots as long as they are made. With the billions of dollars forecast for robot sales through 2020, and the trillions of manufacturing dollars dependent on robot-driven automation, who makes the robots, sets the standards, and controls their distribution, is seriously important.

Then comes the AI factor

Here’s a novel thought that has been bandied about amid the waves of reports on the future impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on manufacturing. Intriguingly dangled at May’s Exponential Manufacturing conference in Boston, AI is speculated to have a major hand in the fabrication process of robots.

Try this on. In the not-too-distant future, maybe there will be zero robot brands. Yes to robots, but no to the names of associated robot manufacturers like KUKA, Yaskawa, FANUC, etc.

Definitely intriguing.

Rather, the future might see a human at a computer (or wearing an AR headset) custom-designing a robot using an AI-powered CAD/CAM program. The completed CAD would then be sent to a “robot foundry” where robots and 3D printers would construct one or many robots according to the human/AI-design specifications.

Of course, branded or brand-less, where this robot-building AI originates from would be important. If it’s Asian or European AI, then the situation is still the same when it comes to influencing manufacturing in North America. If, on the other hand, the AI is native to North America, wow! that changes everything.

Maybe zero is more important than anyone thought.