"We're not a training nation"

The Future Knocks Once. Let’s Be Ready This Time

Will COVID expose other vulnerabilities like the lack of U.S. “reskilling and worker training” capabilities?

“Our best guess is something like 60 percent of the employment reduction is going to be temporary, and 40 percent is going to be permanent.”

—Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago

Will this come to pass?

We hear and read about it all the time: As automation technology takes people’s jobs, does technology, in return, then create ever-newer jobs for those displaced by automation?

The answer may well reside in this question: Is the vulnerability of the U.S. medical system as exposed by the COVID pandemic analogous in any way to our potential vulnerability for TIDE (technology-induced displacement of employees)?

If so, we’re in for a very long, hot summer…and beyond.

BTW: TIDE is a phenomenon coined by Littler attorneys.

As the Littler attorneys ask: “With the fast-paced arrival of innovative and transformative technologies, will workers whose jobs are most likely to be disrupted have the skills and training required for the new jobs being created?”

In these stark times of COVID-driven layoffs, furloughs, industry shutdowns, store closings, and bankruptcies, the question asked by those Littler attorneys is now more important than ever.

And the fast answer is: Not likely

Way back in 2018, The Atlantic, with support from the Lumina Foundation, authored a series of articles, with the overall title What Makes a Worker. The article series sheds light on the very question that the Littler attorneys posed.

The title of the lead article is disconcerting, The False Promises of Worker Retraining, and the well-researched and well-written article that followed is even more disconcerting. The author, Jeffrey Selingo, writes: “Despite assurances from policymakers that retraining is the key to success, such programs have consistently failed to equip workers with the preparation they need to secure jobs.”

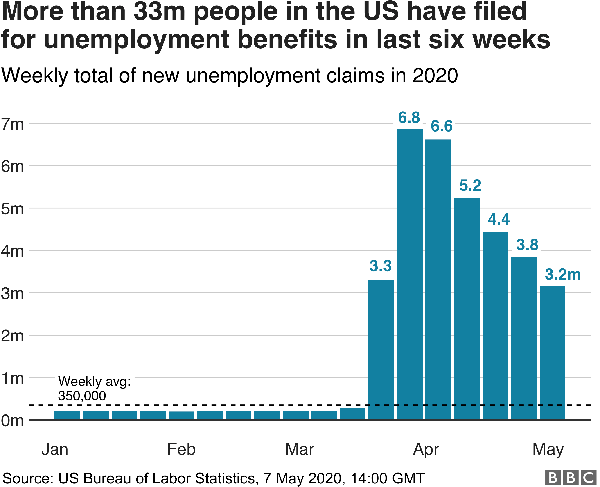

Well, 36 million Americans are now unemployed and have filed for unemployment compensation.

The 60/40 job split

As if that mega-number is not frightening enough, the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago is out with a paper estimating that “many of the layoffs people expect to be temporary will actually become permanent.”

Unlike the Great Recession shutdown of 2008, this time around it was the U.S. voluntarily—and temporarily—shutting down the country. Right?

So, after temporary turns into a fresh restart, shouldn’t then everyone go back to work as usual? Turns out, no.

The authors of the unsettling Becker paper, COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock, write: “Our best guess is something like 60 percent of the employment reduction is going to be temporary, and 40 percent is going to be permanent,” said Nicholas Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University and one of the co-authors of the paper. “Looking through history at previous recessions, often these temporary layoffs unfortunately turn out to be permanent.”

So, 40 percent of 36 million unemployed is 14,400,000! For the sake of argument, let’s say that the final number is half that figure: 7,000,000. Add that to the 6,000,000 still out of a job and “no longer looking for work” following the Great Recession (2007-2009), and the U.S. grand total of semi-permanent unemployed could balloon to 13,000,000, which suddenly becomes a reskilling/ retraining challenge of mind-boggling proportions, and a living nightmare to those unemployed through no fault of their own.

And if such a grim number comes to pass, is the U.S. prepared and capable of reskilling/retraining these citizens for new roles in the workforce?

The Atlantic’s overall article series offers a resounding no.

Here following are excerpts pulled from The False Promises of Worker Retraining article that show the reasons why:

The False Promises of Worker Retraining (excerpts)

- Despite assurances from policymakers that retraining is the key to success, such programs have consistently failed to equip workers with the preparation they need to secure jobs.

- As a result of the 2008 recession, the U.S. shed 1.6 million manufacturing jobs requiring just a high-school diploma; only 200,000 returned. [That’s 1.4 million who never returned to their former jobs]

- Dollars delivered to the states through the federal government’s primary workforce-retraining program have been slashed by 22 percent since 2009.

- Despite decades of investments by the federal government in a patchwork of job-retraining efforts, most have been found to be ineffective according to numerous studies over the years, and it remains unclear to experts whether the programs are even up to the task of preparing workers for the new economy.

- The Labor Department’s Trade Adjustment Assistance fund…has been around since the early 1960s, and in recent years has paid upwards of $11,500 per eligible person for training. But a 2012 assessment of the program found that, four years after completing training, only 37 percent of its employed participants were working in their targeted industries.

- The trade-assistance program is just one of 47 federal job-training programs across nine agencies that the Government Accountability Office identified in a 2011 report. Most were tiny and mainly served the unemployed struggling to find work. The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act signed by President Obama in 2014 was a bipartisan attempt aimed at consolidating the hodgepodge of programs.

- Entire occupations and industries are expanding and contracting at an alarming pace, and the skills needed to keep up in almost any job are churning at an increasingly faster rate. As a result, there is often a gap between the jobs employers need to fill at a given moment and the skills of available workers.

- Federal retraining programs remain rooted in the industrial era in which they were created and have largely failed to evolve with the global information-based economy in which technical know-how trumps muscle.

- “In previous decades, we’d have down cycles where workers were laid off and then they’d be called back,” said Mary Alice McCarthy, the director of the Center on Education & Skills at the left-leaning think tank New America. “Now there is a restructuring in most industries where people aren’t ever going to be called back or ever find jobs in that industry again—and we don’t have training systems that allow for that.”

- Workers who have been laid off through corporate downsizing or because their jobs were shipped to a foreign country don’t want to dedicate the time and effort needed to go through retraining without the pledge of a sure-fire job with the same or a better paycheck.

- The federal government has called for better cooperation between industry and community colleges in designing programs that prioritize what it refers to as “demand-driven training,” so that dislocated workers aren’t learning skills that are outdated by the time they graduate.

- Speed matters when it comes to enrolling into training programs workers who were recently laid off. A significant delay—a wait of a year or more—often permanently hinders a worker’s chances at finding a new career and limits his or her lifetime earnings.

- Retraining is most successful when workers actually start it before they leave their old job. “If you wait until they are out of a job, the emotion of losing a job comes into play; they start to get accustomed to not working, they get rusty,” said Jane Oates, who was an assistant secretary in the Labor Department during the Obama administration.

- A major development is that the pathway to retraining these days almost always runs through a college campus. Even most manufacturing jobs now demand some sort of education after high school. But many of the workers who require retraining dropped out of college, if they went at all. Perhaps the biggest hurdle in retraining displaced workers is that some of them have little interest in going back to school.

“We’re not a training nation”

Anthony Carnevale, research professor and director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, sums things up quite simply: “We’re not a training nation.”

Having served on President George W. Bush’s White House Commission on Technology and Adult Education and on President Bill Clinton’s National Commission on Employment Policy, Carnevale is all too familiar with the passes as training workers in the U.S.

“We spend $6 billion, $7 billion on [the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act],” he said during an interview with The Atlantic. “If we were funding it at the same service level we funded [the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] during the Carter administration, it would be at $30 billion. We shifted from training during the Clinton administration, which decided, during the second term, that training wasn’t working. It was too narrow.”

“The training budget in the U.S. government is $8 billion, and the government and families spend over $500 billion dollars on college education. The model in America is “high school to Harvard.”

Clinton’s second term began in 1996; that’s over two decades of less than zealous attention toward training.

All of which means that some 14 million unemployed may be looking at a less than zealous training experience.