Battling TIDE

Does America Need a Czar of GenAI Reskilling?

How should America go about reskilling millions of workers whose jobs are being targeted by automation and artificial intelligence?

Scary headline from scary article. Can America let that happen?

“It Won’t Be Pretty’: How the Next Decade’s Technological Tsunami Will Change Life as We Know It” —Vanity Fair

The automation challenge & reskilling America

Harry Hopkins during the Great Depression, Vannevar Bush during and after World War II, J.C.R. Licklider in ARPA’s push for the Internet, Gen. Lucius Clay building the Interstate Highway System, and Werner von Braun’s visionary pioneering for NASA’s response to Sputnik.

George Marshall and his magnificent Marshall Plan could grace the list, however, the main beneficiary was Europe and not America.

Once upon a time not too long ago, these trusted individuals of great integrity and unlimited vision were given unlimited power and unlimited funds to get their respective jobs done ASAP. …And they did! Can America find such individuals to do it again?

Hopkins, Bush, Licklider, Clay, and von Braun were, in effect, powerful czars who reacted to and successfully challenged threats to America. Better, the perceived threats that each faced were not only vanquished but reverse-engineered into fantastic job-creation machines.

If America wants to avoid a tsunami of unemployed citizens, it might want to go looking again for a worthy czar.

Since America isn’t the only industrialized nation hoping to dodge the automation bullet, czar-picking might be a good idea for all of them to ponder.

Everybody’s talking about automation

America knows from its past that big problems require big solutions, which mean big money from big government. It’s that simple. Leave things up to the States or to big business and invariably nothing gets done or things get done piecemeal to the satisfaction of only a few.

TIDE, or Technology-Induced Displacement of Employment (TIDE), is the next big problem on America’s plate, and its solution is going to require all the other “bigs” that usually attend big problems to converge. TIDE is simply too big for the States and way too big for big business, while big government is currently either or both too slow to take action or too distracted to take any real notice of the calamity headed its way.

The causal agent fingered as the reason for TIDE is workplace automation in all of its various forms and states. From welders to Wall Street wonders, workplace automation and artificial intelligence (AI) are substituting machine labor for human labor. While increasing productivity and the speed of productivity benefit industry, ultimately, such a reformation in getting work done will mean fewer jobs by the millions for humans and evermore jobs for machines and their kin.

From the halls of Congress to dinner tables everywhere it’s been called a cataclysmic crisis in the making. Why is that? Simply because, as researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco have reported, in a scary paper titled Are Workers Losing to Robots?: “While it [automation] has increased labor productivity, the threat of automation has also weakened workers’ bargaining power in wage negotiations and led to stagnant wage growth,” which means the “labor share” of GDP (the portion of national income that goes to workers) has shriveled “from about 63 percent in 2000 to 56 percent in 2018.” And it isn’t going back up any time soon. In fact, it is headed further south, and picking up speed as it goes.

It’s the kind of ominous news that prompted Elisabeth Reynolds, executive director of the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future, to warn: “If we stay on the trajectory we’re on currently, we’re going to have greater income inequality, less social mobility, greater political unrest and greater income insecurity.”

Her reasoning: “Fast advances in AI and robotics threaten to fundamentally alter both low- and high-skilled jobs, increasing the urgency for political leaders to address the issue. Unchecked, job losses from automation could knock out bottom rungs of traditional career paths, worsen inequality and increase political polarization.” All of it particularly bad news for the “labor share” of GDP and the millions of Americans who go to work each day to earn it.

Glowing like a hunk of kryptonite in her remarks: “increasing the urgency for political leaders to address the issue.”

It’s an intense glow growing brighter to which Congress has turned a blind eye. A couple of hours watching C-SPAN, as clueless politicians frame inane questions for panels full of automation and AI experts, is enough to show how deeply detached the country’s elected officials are from Reynolds’ alerts.

It's All Been Done Before:

Reskilling America's Workforce

If America needs to reskill itself en mass in order to prepare for the disruption from automation and AI in the coming transformation of the workplace, the gang on the Hill is showing itself to be ill prepared or unwilling or both to take action.

A czar of reskilling could get the job done. America has leaned on czars in the past. Why not now?

A long time in coming

As MIT’s David Autor, Frank Levy, and Richard Murnane pointed out in 2003, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has known since the 1960s about the harmful effects of automation on jobs and careers—blue and white collar alike.

Back then, the affected jobs were routine ones like posting clerks, checking, and maintaining records; filing; computing; or tabulating, keypunch, and related machine operations. All those millions of jobs, and the people who worked them, are long gone.

As the Oxford Martin School furthers in Automation and the future of work – understanding the numbers: “In his 1960 essay, The Corporation: Will It Be Managed by Machines?, Herbert Simon predicted the decline of routine jobs, arguing that computers hold the comparative advantage in “routine” rule-based activities which are easy to specify in computer code.”

Hence, the reason for the disappearance of all those routine jobs.

These days, however, automation has a half-century of computerization under its belt, and has now added robotics and AI to its digital quiver. The end result of which means that any job or work activity that can be fully or even partially routinized, office or factory, is a goner.

Automation, previously content with lopping off routine jobs by the hundreds of thousands, now presents itself for work as a team of computers, robots, and AI. This converged trio is gathering momentum to routinize work by the hundreds of millions of individual jobs and tasks. It’s a newly emboldened face of technology that finally—after fifty years of evolution—is now forcing the issue—thrusting change or else upon reluctant politicians…as well as the “labor share” of GDP a/k/a job holders. Us!

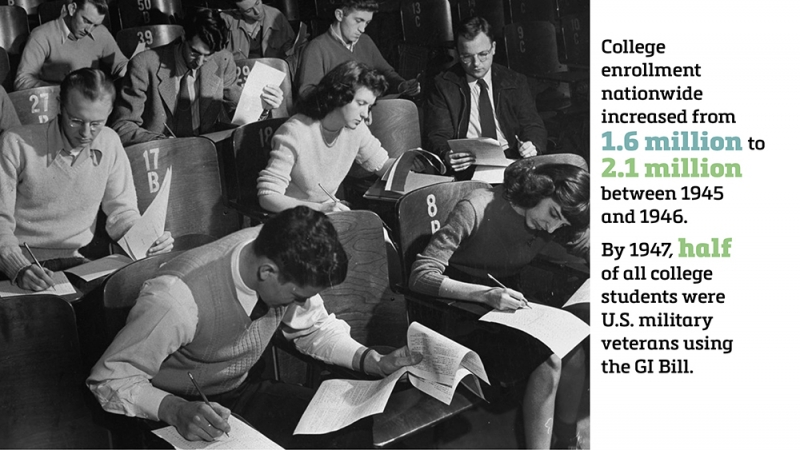

Neither the individual States nor corporate America has the resources to mitigate, let alone vanquish, the threat of TIDE. It’s a federal job from the get-go; it’s a reskilling enterprise needing in scope something similar the GI Bill (1944), but on steroids. The GI Bill helped 9 million better their lives!

Help wanted: A Czar of Reskilling. And there’s precedent for it to be successful.

When everybody liked Ike

Maybe it was because Dwight Eisenhower had been a war-time general (as in Supreme Allied Commander) plus president of a university (Columbia) that he acquired a knack at czar-picking for technology.

Technology had more than helped him win a war; and hanging out at a superb research university post-war had helped him to appreciate the people who made science and technology possible. To President Eisenhower (1953-1961) fell the tasks of dealing with the three most important technological challenges of the 50s and 60s: the Internet, the Interstate Highway System, and Sputnik.

He was the first president to hire a science advisor (James Killian, MIT’s president) and the first to establish the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), both in 1957. He felt sure that in responding to the Internet, the Interstate Highway System, and Sputnik that the resulting technologies would spawn new industries and millions of new jobs would ensue. He was right.

A popular president, winning both the 1952 and 1956 elections by landslides, Eisenhower had carte blanche to take on any emergency facing the country. Sputnik was the biggest, and Eisenhower felt basic research held the keys in overcoming the tech gap created when the Soviets launched the first satellite.

The Advanced Research Products Agency (ARPA; today, DARPA) in 1958 was his first move. ARPA would be run by J.C.R Licklider (author of the breakthrough Man Computer Symbiosis, and Czar Licklider would report to Neil McElroy, the former president of a soap company, Proctor & Gamble (P&G), who Eisenhower had appointed as Secretary of Defense (1957-1959). While at P&G, McElroy had established a well-funded “blue-sky” research laboratory, “one of the first of its kind in American corporate history.”

The formula created by this network was obvious and returned tangible results. Czar Licklider (and his hand-picked successor Bob Taylor) could sort through and fund any project that they deemed appropriate to the task. Only McElroy could thwart ARPA’s basic research efforts. He never did. Six months later, NASA came into existence and followed the same formula of basic research.

ARPA’s basic research evolved into applied research which then morphed into brand new industries; IT is its most notable achievement. It was the beginning of the era computerization, and IT’s DNA forms the bedrock of the present boom in automation.

Managers of today’s TIDE challenge may well benefit from taking a look back in the history books at Eisenhower’s path to success.

Selecting a Czar of GenAI Reskilling may be a good place to begin.