“AI and robotics are not separable.

Big changes happened, and we could not catch up.”

-Minoru Asada,

Osaka University.

The Gloom Over Japan’s Robotics Future

Are the very people whose robots forever changed manufacturing now getting outdistanced by Industry 4.0, AI & “smart” robots?

Gloom rolls in

In East Asia, both China and Korea have mastered the technology, science, and art of breathing intelligence into robots. For the most part, Japan has not; and oddly, doesn’t seem to appreciate how important smart machines are to its global future.

Yes, the trade publications say the country is “scrambling” to correct the situation, but just what that scrambling entails is a major mystery.

“AI and robotics are not separable,” says Minoru Asada, an emeritus roboticist at Japan’s Osaka University. “Big changes happened, and we could not catch up.”

The result, these days Chinese AMRs are whizzing around Japanese warehouses, while Korean industrial robots are delivering smart robotics to its factories.

Worse for the Japanese economy as well as its national pride is this from Nikkei Asian Review: “Japan’s gross domestic product unexpectedly shrank for a second straight quarter, confirming that the nation’s economy has now slipped behind Germany to become the world’s fourth largest.”

Japan #4!

Meanwhile, the big picture of demographic decline looms ever larger as the country gets old and goes from gray to white, while the fertility rate continues to slump, and workers get scarce.

Factoid: The average age of Japanese farmers is 70!

Even seemingly little snags can unexpectedly haunt the economy. For example, unlimited overtime for truck drivers is going away (15-hour shifts, six or even seven days a week), which will put a major crimp in an already strained logistics industry. Solution: Need more drivers. Fact: Not enough available.

Japan’s problems make it a prime location for robot-driven automation. However, recent research in Nature and from the Oxford Martin School portray Japan’s industrial automation efforts as ranging anywhere from lagging to stagnating. Graeme Mcdonald at Citigroup points out the best automated factories in Japan are those that make robots: “Production at some of Japan’s leading robotics companies is already nearly fully automated.” But that automation doesn’t extend much beyond those robot factories.

Where to begin?

“An expectation that they would be the global leaders in robotics has not been fulfilled,” cautions Manuela Veloso, head of artificial intelligence (AI) research at investment bank JPMorgan Chase, and a professor emerita of computer science at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University.

Factoid: According to TechWire Asia: Japan will face a deficit of 789,000 software engineers by 2030.

Noriyuki Kojima, co-founder of Japanese startup Kotoba Technology: “Japan’s trailing position in the field of generative AI largely stems from its comparative shortcomings in deep learning and more extensive software development.”

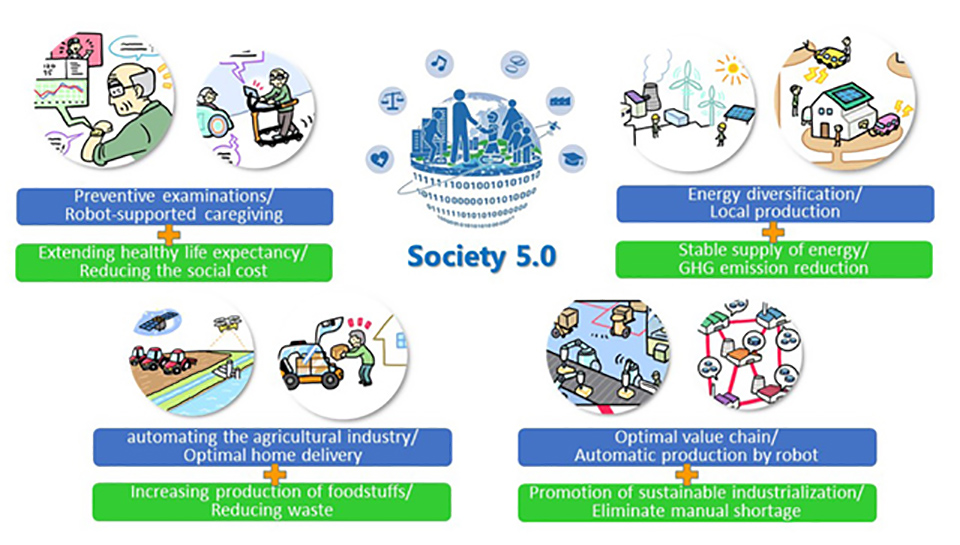

“In the early 2000s the Prime Minister’s Cabinet offered Innovation 25, a policy initiative that said it would make Japan an “innovation” society by 2025. As that year approaches and with little to show for its efforts, Innovation 25 has recently given way to Society 5.0, another Cabinet Office initiative that defines a new societal iteration as: “A human-centered society that balances economic advancement with the resolution of social problems by a system that highly integrates cyberspace and physical space.”

Lots of money and a decade of R&D would seem to be the first order of business for Japan in order to dispel a bit of the gloom. Japan has precious little of the latter but an abundance of the former; maybe the government and the Bank of Japan need to pour billions of dollars into the problems, even if some large portion of it is squandered. China’s Xi Jinping, in a speech from 2015, called for a “robot revolution” in a nod to automation’s vital role in raising productivity. As it did with its steel industry and later with EVs, China lavished billions on robotics, and out came “Made in China 2025.”

See related:

China’s “Robot Dividend” Has Three Faces

Will China become the first of the fast-aging industrialized nations to transform a severe onrushing demographic decline into a robot dividend?

Some things might never be achievable, such as Japanese researchers abroad up to their elbows in cutting-edge robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), who then return home with the acquired skills. “I’ve been at Carnegie Mellon for 30 years, and we’ve had a handful of Japanese PhD students,” Veloso says. “How many Chinese students have we had? Hundreds.”

The Nature Index ranks Japan seventh in the world for its overall AI and robotics research. None of Japan’s research institutions make it into the top 30 for AI and robotics, based on the Nature Index from 2015 to 2021; and Japan is also increasingly being outperformed by its neighbors in East Asia. Korea, for example, increased its index share in AI and robotics in the Nature Index by 1,138% between 2015 and 2021, whereas Japan’s increase was 397% over the same time frame.

See related:

Korea Gets Serious About Robotics

“The government plans to invest $2.3 billion by 2030 to expand the robotics industry to a globally competitive level,” about $329 million annually from 2024-2030

Two newest initiatives

ROBOCIP 2024 is a new public-private group “to facilitate the introduction of robots and cobots to nation’s 3.5 million SMEs”

Accenture Alpha Automation 2024 (jointly owned by Accenture and Mujin Robotics) An article from AIThority states the plan’s focus: Accenture and Mujin Establish Joint Venture to Bring AI and Robotics to the Manufacturing and Logistics Industries.

Mujin Robotics and Accenture are partnering with a plan to establish a “new paradigm” in automation in Japan.

Mujin Robotics is probably Japan’s best example of an AI-driven robotics vendor; and of course, Accenture is a well-known Dublin-based, Global 500 information technology services and consulting giant (revenues for 2023 of $64.1 billion).

Whatever the ROBOCIP 2024 and Accenture Alpha Automation 2024 plans can do seem to be a bit of a stretch. Each seems more like a band aid trying to staunch a major wound than an all-out, nationwide effort to bring technology to bear on very serious problems needing monumental remedies.

As each has just been launched, we’ll have to wait and see…while time whizzes by.

Maybe Japan needs another “divine wind”

Since the end of World War II, Japan has been jumpstarted in technology by foreign influences in three critical industries that it then went on to dominate: 1. the automobile assembly line building war materiel for the U.S. during the Korean War; 2. buying Bell Labs’ transistor patent in 1954 and using it to build the world’s second all-transistor computer (Bell Labs’ TRADIC was the first), and then; 3. the Kawasaki-Unimate agreement of 1968 that produced Japan’s first homegrown industrial robot.

Historian Yoneyuki Sugita, in his book Pitfall or Panacea: The Irony of U.S. Power in Occupied Japan, 1945-1952 likens the first event to a “divine wind” rescuing Japan’s post-war devasted economy. Japan went from a $300 million trade deficit in 1949 to a $40 million trade surplus by December of 1950. Of course, we all know what Kiichiro Toyoda then did with that Dodge truck assembly line (Toyota Motor Corporation). Another small company called Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo took the Bell Lab’s transistor and became the SONY Corporation. And the robot agreement, well, it catapulted Japan into being the emperor of all robots.

One thing is certain, Japan needs major help…and very soon. Another divine wind would be most welcome.