Buy Robots...Make Robots...Export Robots

China’s “Robot Dividend” Has Three Faces

Will China become the first of the fast-aging industrialized nations to transform a severe onrushing demographic decline into a robot dividend?

“Cross the river by feeling for stones.”—Deng Xiaoping

.

The Problem: Demographic Decline & Economic Decline

Remedy for demographic decline. How about robots?

Things are looking quite possible that China can cobble together a hurry-up in automating its industry, with diligence in building out homegrown robot production, with enough of a successful push in overseas sales of robot and automation systems to remedy the ills of demographic decline.

The oft-maligned, job-stealing industrial robot may well be just the ticket to creating a youthful robot dividend that snatches victory from the jaws of a shrinking population that experts say won’t bottom out until the 2080s.

Just to be clear, demographic decline is the reduction over time of a country’s population, and its inability to regain that population because of a national birthrate that’s too low (replacement birthrate is 2.1 babies per woman). For aging countries, 1.1 to 1.6 is more the norm. The elderly include China, Korea, Japan, Russia, and Italy; Germany and the U.S. escaped because of immigration. If successful, China could well become a model for avoiding a greater catastrophe, seeing that these elderly nations represent a mega slice of global GDP.

As a historical note as to what constitutes a good fertility rate, here’s a Wall Street Journal observation: “World War II led to an explosion in government spending that restored full employment, and the baby boom after the war’s end put to rest fears of declining population. The U.S. fertility rate leaped from 2.3 in the 1930s to 3.6 in 1960.” And that’s what made America’s wealth soar and dominant among world economies.

More to the point of China’s woes, according to Ruchir Sharma, a former head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley: A declining population generally correlates with economic decline — roughly a one-percentage-point decline in economic growth for every percentage-point decline in population. Compounding sketchy economics are missteps from China like the countrywide COVID shutdown, which added more personal debt to its citizens as well as to their government.

One way, say economists, to level the playing field with a demographic decline and tumbling productivity is technology. Until the 2080s roll around with increases in population inching up again, technology is just about all there is in the sparse cupboard of economic growth. Add the timely emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) to the mix, and technology may be the difference maker while awaiting the sixty years or so for the 2080s to show up. Like this from Hiroaki Sasaki writing in ScienceDirect’s Growth With Automation Capital and Declining Population: “Even though the population is declining, per capita output can continue to grow at a positive rate depending on condition.”

And the most prominent factor aiding both declining workers and their declining productivity is robot-driven automation.

And that’s not just a problem for China to figure out; the first rustlings of demographic decline are slipping into Germany. The headline of a Reuters article this week says it all: As Baby Boomers Retire, German Businesses Turn to Robots. “The German Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) says more than half of companies are struggling to fill vacancies, at an estimated cost to growth in Europe’s largest economy of nearly $109 billion.”

China now realizes what the technological remedy could look like and is playing its technology card to the hilt. Lucky for China it’s not starting from scratch; the last two Five-Year Plans (the 13th from 2016-2020 and the 14th from 2021–2025, plus buying every robot in sight since 2013, plus Made in China 2025, have built the base that it will need to secure the robot dividend. Others among the elderly nations aren’t so lucky.

The three faces of China’s robot dividend

First off, China continues to be the greatest industrial robot buyer in history and every year it seems to set another world record doing it. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), for 2022 China installed a record 290,258 industrial robots, 5 percent more than in the previous year. During the first six months of 2023, the number of industrial robots sold during this period was 144,288 units, an increase of 17% compared to the previous year. Worldwide, 553,052 industrial robots were installed; more than half went to China.

And China promises to keep up the buying. From 2021 through 2025, with the aim to boost automation in manufacturing, the goal is to push annual growth of 20 percent in robotics sales while, at the same time, to develop a select group of industrial champions to help to double “robot density”.

“By 2025, China wants to build a least 500 smart-manufacturing-model factories to lead the development of smart manufacturing and to cultivate at least 150 smart-manufacturing-solution providers.” Those numbers are astounding but, in China, anything is possible given the country’s track record over the past thirty years or so.

Industry experts in Chinese production say that this rapid development in automation technology is helping alleviate China’s labor shortage caused by aging. By 2050, China hopes to replace more than half of the country’s labor shortage, which would equate to 100 million to 140 million labor hours a year…or about 3,500,000 workers.

Hu Haifeng sales manager at Beijing-based Rokae Robotics claims that the impact of the pandemic lockdowns made the entire manufacturing industry realize that production must be automated.

Automation is making inroads swiftly. “Manufacturers with a yearly output of $41 million previously needed about 100 workers to maintain. Now most are largely unstaffed, requiring only four or five workers to keep up production.”

“Automation of production lines has actually helped retain factories and complete industrial chains,” said Xue Ping, a textile furniture manufacturer and exporter in Zhejiang.

Another benefit to China’s manufacturers said Xue: “Such factories will not move to Southeast Asia, because productivity gains have created huge scale and cost advantages currently unmatched by any other country.”

The idea behind that is why would any manufacturer contemplate reshoring or nearshoring away from China when China’s robots operate for less than $3.00 per hour. Sure, there’s the constant specter of supply-chain screw ups, but then again, under $3.00 per hour? Seems like a no-brainer.

“The robotics industry is now approaching a tipping point towards a revolutionary leap, containing huge investment opportunities and surging development momentum,” said Xin Guobin, a vice-minister for industry and information technology.

He also said China will continue to promote the government’s $1.4 billion Robot Plus Application Action Plan, which aims to increase the use of robots in 10 sectors – including manufacturing, agriculture, logistics, energy, healthcare, education, and elderly services.

See related:

Homegrown robots

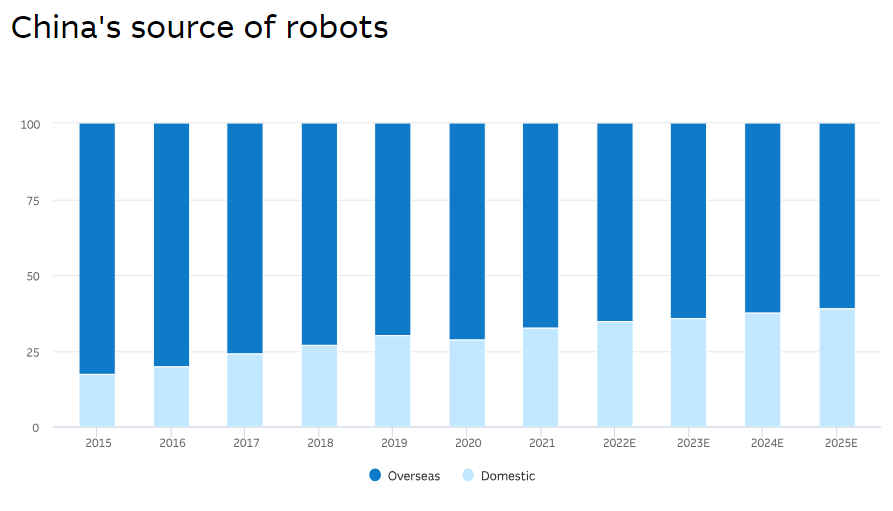

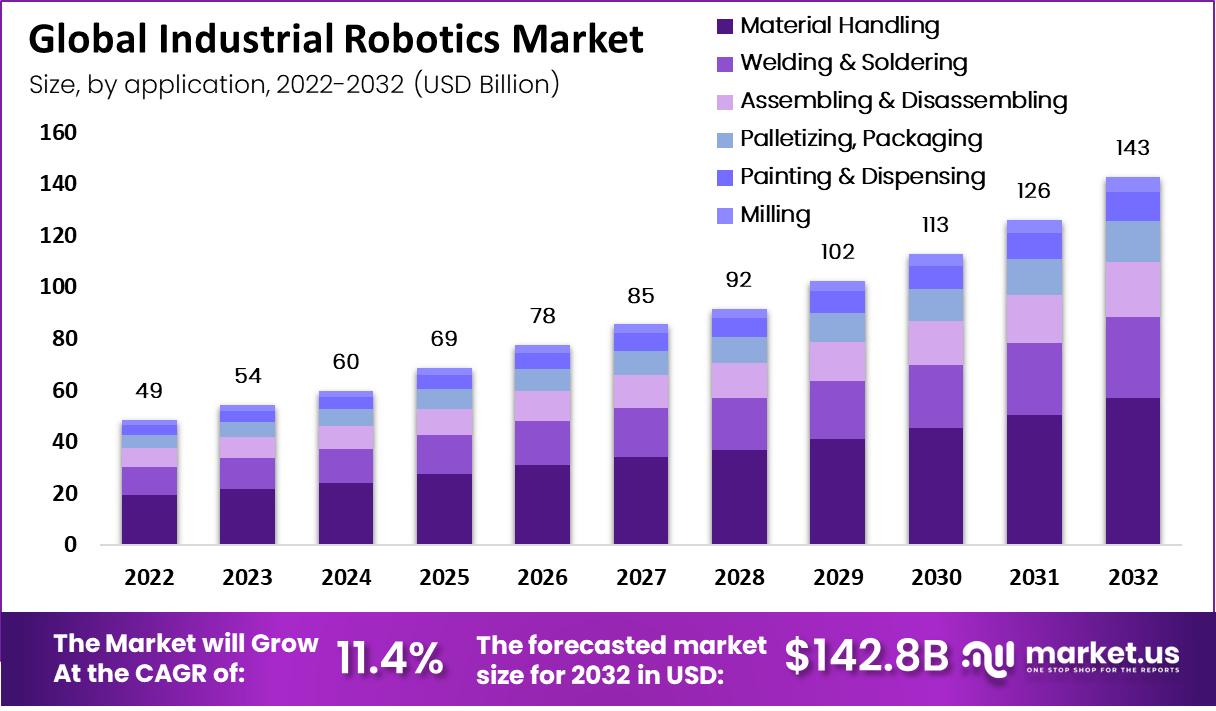

The second face of China’s “robot dividend” is its own indigenous robot industry, which “Made in China 2025” said would control 50% of the industrial robots sold in China. To date (2023), it hasn’t. Indigenous, China-made robots have about 30% of the market. But when the global industrial robot market is $17 billion in 2022 ($32 billion by 2028 International Federation of Robotics (IFR)); and when $9 billion of that number is spent by China to acquire industrial robots, then even 30% is sweet (which would be $2.9 billion paid for domestic product).

The more industrial robots designed and built in China…and sold there, all the better for China. Plus, there are 1.5 million industrial robots operational in China today that need ongoing maintenance support and parts. If all or a large share of that industrial robot production was native to China, China would then have greater leverage in automating the entire nation.

“The domestic share of industrial robots in China doubled from 17.5% in 2015 to 35.5% in 2022, according to MIR Databank.” The growth of Chinese robot companies accelerated significantly over the past few years partly due to supply chain disruptions that made it harder to access foreign products; partly because of a growing need for automation in small and midsize manufacturing companies amid pandemic-era labor shortages, all of which were subsidized by the government.

Chinese industrial robot manufacturers are gearing up to challenge the long-established dominance of global giants by taking advantage of the mandate to automate the country’s industries.

“Chinese industrial robots still have some catching up to do in terms of technology,” reports the Nikkei Asian Review, “but they are roughly 30% cheaper than Japanese and European counterparts, an opening Chinese manufacturers are set to exploit to gain ground in their home market.

“Chinese factories prefer the foreign-made robots “because their movements are more accurate and they are more durable,” said a Chinese industry insider, acknowledging that there is a technological gap in decelerators and other core parts and software.”

However, these high-performance robots from foreign players are pricey, which means only a small number of companies can afford them and, in turn, has hindered the spread of industrial robots in China. Many midsize manufacturers in China are unable to tap robot resources, and this is where domestic robot makers see their opportunity.

Interestingly, this SME market is part of the same vast market ($500 billion) that the SoftBank/Symbotic venture (GreenBox Systems) claims to exist (for their Warehouse as a Service (WaaS) logistics robots).

“After years of being bested by Japan’s Fanuc, Swiss player ABB and other powerhouses, Chinese industrial robot manufacturers have gone on the offensive, ramping up capacity to boost their domestic market share from 30% to the government-set goal of 50%.”

Not many outside of China are familiar with industrial robots manufactured by the likes of companies with unfamiliar names: Siasun, Estun, Efort, or QJAR; exception being household name KUKA (former German robot heavyweight) has been quietly owned by China’s Midea Group since 2016. Chinese manufacturers have even developed ten top-notch cobots, three of which ELITE, AUBO, and JAKA, have had demonstrated overseas sales success.

All of that “unfamiliarity” may start to change beginning in 2024, especially if it means national survival.

If the robot dividend means keeping billions of dollars (or yuan) at home rather than in foreign banks, then China will need to thank its lucky stars that it started building out a massive homegrown robotics industry circa 2000. Other than Japan, Korea, Germany/Austria, and the Swiss/Swedish ABB, not many are willing to take on the near-impossible task of becoming a robot-producing nation.

Overseas sales of industrial robots

Better than keeping billions at home is making billions with overseas sales. There’s a world out there that needs to be automated in a hurry, none sooner than China itself. To date, it’s been the logistics robots from Geek+, Quicktron, and newcomer Hai Robotics, that are China’s foreign-selling money makers and best-known automation brands.

High quality industrial robots have a huge place in the world of automation, regardless of who builds them. Siasun, Estun, Efort, or QJAR quality robotics will get tested in smaller markets, and then scale.

With China producing 28% of the world’s manufacturing output, there’s a galaxy of factories (Statistica reports over 800,000) and a universe of warehouses, DCs, and other, smaller storage facilities according to China’s Blue Book that will need to address automation or become irrelevant and get torn down.

One Chinese robot maker is already in the game. Shanghai-based JAKA Robotics is seeing its cobots getting popular with Toyota. If JAKA’s cobots can pass muster in Japan, the Emperor of All Robots, then China is putting out a good product. “JAKA supplies an exclusive line of collaborative robots to Toyota Motor, called the “For Toyota” series.”

JAKA’s founder and CEO Young Li said: “We want to produce robots to Japanese quality standards.” So much so, in fact, JAKA is building a cobot plant in Nagoya, in the heart of Japan’s car builders. Li added: “We are also building a new plant in China’s Jiangsu Province in response to growing demand,” which will have an annual capacity of 50,000 units and will be completed in early 2024.

With SoftBank money invested in both JAKA and Symbotic, maybe JAKA will get pulled into the GreenBox planning, which would be a fantastic boon to China’s cobot-making industry.

China has itself to thank for creating and building out this nascent “robot dividend”, for staving off, and maybe even reversing, the specter of demographic decline. The world needs for China to pull it off; the Middle Kingdom is just too important for it to fail its robot dividend.

And if successful, others are sure to follow.