October 29, 1969!?

International Internet Day on October 29th celebrates what many consider the most important invention inhuman history: the Internet.

It’s hard to fathom a world without the Internet. The Internet provides instant access to information. Search engines make this information easy to attain.

In 1969, Charley Kline, a student programmer at the UCLA transmitted a message on 29th of October in 1969 from the computer housed at the UCLA to a computer positioned at the Stanford Research Institute’s computer. 350 miles distant.

That’s the transmission that is celebrated every October 29th.

Unfortunately, that’s not true. The date is wrong, the distance is wrong, and the two computers hooking up were not the first.

The real story is a fabulous look at engineers and their need to democratize and share knowledge well before the Internet came into being. Here’s how two engineers, Larry Roberts and Tom Marill sent digital packets over 3,000 miles to each other…in 1966. The fabulous part is the WHY.

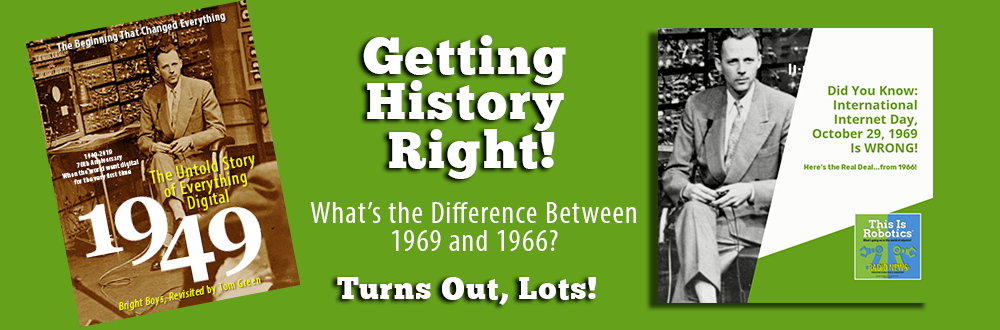

My newest book The Untold Story of Everything Digital has as one of its central characters the Whirlwind computer all 2500 square feet of it. Whirlwind was the first real-time digital computer. Built by Jay Forresters and his band of brash, upstart engineers. They shocked the world with that first-ever digital computer.

They instantly went from being called brash upstarts to global experts of the highest regard.

Whirlwind was not only the first-ever real-time, digital computer, but also first mother of digital computers.

Mother Whirlwind produced an abundance of offspring. Fecund is what I guess you’d call her.

Mother Whirlwind had 30 clones of herself made on an IBM assembly line for use across the U.S. and Canada for the first-ever air defense system. Whirlwind’s clones, renamed for the military, were

Sometimes History Gets It Wrong

When MIT moved its military projects out of Cambridge to a new facility in Lexington, MA called Lincoln Laboratory, Mother Whirlwind couldn’t tag along with the brash, upstart engineers who built her when they set up shop at Lincoln Laboratory.

So, a clone of hers was made in the basement of Lincoln Laboratory, an all-transistorized version called TX-0 or tixo, which was soon given to MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics, while another all-transistorized Whirlwind clone was built called the TX-2

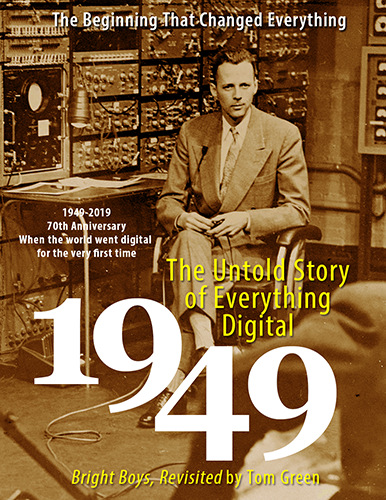

Jay Forrester and his engineering crew who had built Whirlwind and tixo…as well as showed IBM how to clone Whirlwind on an assembly line, set about building the TX-2

Clear across the country in Santa Monica, the System Development Corporation, built a transistorized version of the Q-7, which was named Q-32.

TX-2 solid-state computer at Lincoln Laboratory with Larry Roberts (Lexington, MA)

AN/FSQ-32 solid-state computer at System Development Corporation with Tom Marill (Santa Monica, CA)

Larry Roberts, at the TX-2, was worried. His fear was that the local networking nodes that were being planned would only serve researchers and the elite. He wanted the common man and woman to share in all the knowledge that would someday cascade over the network.

He believed in what J.C.R. Licklider called the Intergalactic Network concept, where everyone on the globe is interconnected and can access programs and data at any site from anywhere.

Over dial-up telephone lines. Larry Roberts showed the feasibility of wide-area networking. The test was to send a single word—login—to Tom Marril in Santa Monica.

The first two letters, the L and the O went fine, then the system crashed. Miraculously, an hour later the system came back up and finished sending the G, I, N. That transmission took place February 6, 1966.

Three years earlier than the 1969 date celebrated every October.

Thank you Larry and Tom, you’re the real deal.