“Development is the only hard truth.”—Deng Xiaoping

China Back in Business with Industrial Robots

A $1.4 trillion “new infrastructure initiative” has put the buzz back into China’s automation quest

“Keep a cool head and maintain a low profile. Never take the lead–but aim to do something big.” —Deng Xiaoping

Time for a little development

“Development is the only hard truth,” said Deng Xiaoping in 1992, China’s visionary leader who made Shenzhen and the China Miracle happen. For example, in 1999, China’s exports were a third of the U.S. A decade later, with a little development, China was the largest exporter in the world.

Deng knew well that as long as China is in development mode, things tend to turn out well. So, why not always be developing something, especially in times like these?

Deng’s words must certainly be in top of mind for President Xi Jinping, because he’s just unleased a $1.4 trillion over six years to 2025 for a new infrastructure initiative that echoes and intensifies Made in China 2025.

The Made in China 2025 modernization drive is very much alive despite the trade war, says Yutaka Miyanaga, an executive vice president at Omron, adding that the Japanese robot maker intends to capitalize on the country’s hunger for factory automation.

$1.4 trillion and Miyanaga’s observation should be reason enough for purveyors of automation gear, industrial robots, and robot parts to start formulating plans for reengaging their brands with China’s automation needs as soon as possible.

“Nothing like this has happened before, this is China’s gambit to win the global tech race,” said Digital China Holdings chief operating officer Maria Kwok, “Starting this year, we are really beginning to see the money flow through.”

More than a tech race

It’s surely a tech race, but one with a desperate face. China, as well as Korea and Japan, is the first place on the planet to face off with the worldwide productivity dilemma that is slowly disrupting access to a sustainable way of living. The rest of the planet has time, not much of it, but sufficient time to think and plan and respond. Not so Asia. And nowhere in Asia is the desperation more critically evident than in China.

In thirty years, China did what no nation has ever accomplished; it raised up a half-billion people out of poverty and formed them into its first-ever middle class. It’s a new middle class, barely a few decades old…it’s fragile.

It’s a middle class that is getting pummeled in 2020. China’s $20 billion in damage from floods that devastated 27 provinces, swine virus, locusts, army worms destroying corn crops, and, of course, COVID, forced a 10 percent increase in food and a whopping 86 percent rise in pork prices. All of which is especially tough on 600 million Chinese, or 42 percent of the population, who earn $145 a month.

Such massive success for China’s middle class has come at a severe price to its land, water and air; basics without which the future for everyone is threatened. Polluted air, for example, kills “a million people annually and costs the Chinese economy $38 billion a year.” Or, as the Guardian noted: Beijing’s air is bad, but its water is worse: 85 percent of the water in the city’s major rivers was undrinkable… 56.4 percent was unfit for any purpose. Any purpose!

Productivity is the key to making middle-class living a sustainable success, yet global productivity is at an all-time low. So, how does China—and the rest of East Asia as well—amp up productivity? Simply put, it’s all about robots. Making the country as productive as possible is critical and robots are the keys to productivity.

Using robots to automate manufacturing is a must-have, and the sooner the better. Hence, President Xi Jinping’s $1.4 trillion. Soon, in addition to industrial robots, there will be critical needs for service robots for everything from healthcare care to agriculture, and much more.

Kai-Fu Lee’s recent piece in The Economist, How COVID Spurs China’s Great Robotic Leap Forward, shows the extra burden and need for speed that COVID has thrust upon China. “The efforts are representative of a broader shift amid the pandemic towards automation, artificial intelligence and digitization,” writes Lee.

“The Chinese economy is undergoing a great robotic leap forward, as it removes human touch-points —literally — in its operations. Online businesses, algorithms and automation save costs, boost efficiency and protect public health. Though the shift predates COVID-19, the crisis has accelerated it…As goes China, so may go business everywhere.”

“Historically, automation tends to happen when economic difficulties coincide with maturing technologies,” explains Lee. “Companies feel they need to cut costs by slashing jobs and trying out new technologies.

“And once a company has replaced an employee with a robot and proven its efficacy, it is unlikely to go back. Robots don’t get sick. They don’t strike. They don’t demand higher wages for dangerous jobs. In fact, they are ideal for dangerous jobs, which in a pandemic is any job that requires interaction with people. It is no wonder that David Autor, an economist at MIT, calls the COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis “an automation-forcing event”.

Quite simply, if you want to keep the manufacturing engine running smoothly at all times, then remove the people from the process. Lots of businesses are doing just that: forcing automation upon themselves because human workers are a liability.

One such model for “total automation” in China is Wuhan’s Yangtze Memory Technologies.

Yangtze Memory Technologies, No.88 Weilai 3rd Road, East Lake High-tech Development Zone, operated at peak efficiency throughout Wuhan’s 76-day COVID lockdown. The factory was totally automated. The only humans were the technical team that operated the factory from a control room, and they were shuttled daily to the factory aboard a special bus.

If the view from the control room at Yangtze Memory Technologies is any indication of future planning, it’s all but inevitable that China’s largest manufacturers, like Midea punching out stoves and washing machines or Haier its microwaves and air conditioners, will see total automation sooner than later. What the experts call: “machine dominated, with low labor content”. That’s the future.

But, of China’s more than 2.5 million factories (according to the China Statistical Yearbook), and an estimated two million warehouses, only a small percentage have been automated to any large extent. The same is true for Korea and Japan.

Looking local

President Xi is circling up the wagons and espousing a China pivot that will pay lots of attention to the needs of the home front. Xi calls it a “dual circulation” growth model with a “focus on boosting local output, while drawing in foreign investment and stabilizing trade.”

“Dual circulation is the new strategy from Beijing in coping with the new world: In plain English, it means “domestic market first,” said Larry Hu, head of China economics at Macquarie Bank Ltd in Hong Kong. “The implementation is not that clear to us at this stage, but the idea is to strengthen China’s grip on supply chain and reduce the reliance on foreign suppliers.”

Foreign robot makers will have to deal with the fallout from “dual circulation” as China draws more heavily on domestic robot manufacturers, which have done a lot of growing up over the last decade, especially since 2013.

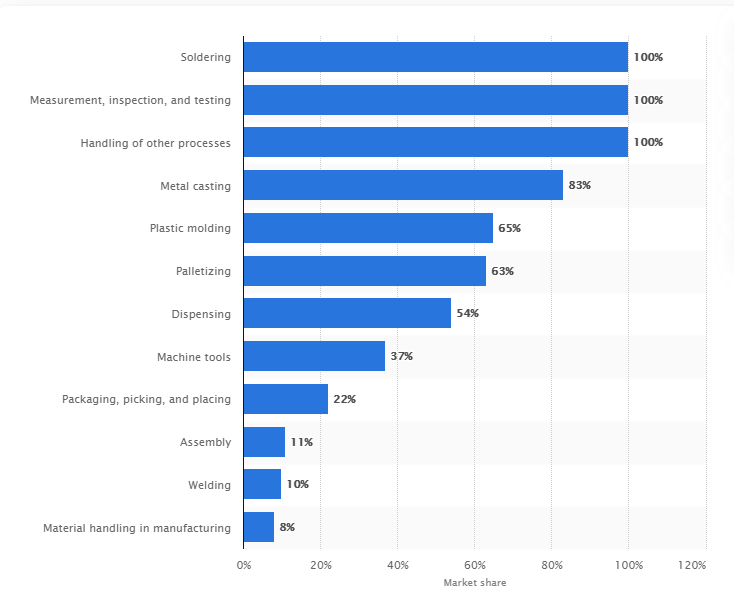

Regarding domestic robot sales by application, China’s homegrown robots, as of 2020, have impacted lots of applications (see chart: Tractica/McKinsey), except for the all-important (see bottom of chart: welding, assembly, picking, packing, placing). Like everywhere else, those applications are elusive. However, the West has honed in on acceptable, and sometimes breakthrough, tech solutions for applications, especially the e-commerce darlings of picking, packing, and placing.

Many of those still-elusive applications fall nicely within the range of cobots. So foreign cobot manufacturers with a solution for the aforementioned manufacturing and logistics sweet spots have a shot a very large payday in China.

Price, post-COVID, will be a huge determinant in who sells what to whom. Why would an SOE, or even a small SME, for that matter, buy a pricey cobot from Universal Robots—made and shipped from a factory 5,000 miles distant—rather than a high-quality cobot like those from local firm AUBO?

China has nearly a dozen domestic cobot makers who have high-quality, very competitive machines. All made in plants in China by Chinese workers. Competitive as well are domestic robot parts, like cycloid gears used as RV reducers. It’s estimated that 36 percent of the cost of a modern six-axis robot are caused by the RV reducers.

China’s Cobots: Big Job Ahead

The stage is set for a wave of cobot automation to sweep across China’s factories.

Price, quality, availability, and service will be paramount qualifiers for automating China.

If the country wished to institute a “Buy China Only” policy for robots and cobots, it would be a simple process to instruct all 300,000 SOEs (state-owned enterprises) to buy from locals. Robot automation of SOEs would, of course, put into jeopardy 75 million jobs, which is a scary proposition for a middle class already uptight from COVID, other viruses, and natural disasters.

The one area where the West has complete and utter dominance is with grippers or end effectors. Advanced chips, on-device computing, 3D vision, haptics, new materials and designs, predictive data, analytics, machine learning, and miniaturization are beginning to co-locate at the business end of a robot’s arm. And all of that co-location is coming together in R&D facilities and factories in the EU or North America. That the robot gripper is evolving into a higher order tool makes a lot of sense, except in Asia.

Robots vs. intelligent robots

The world has quickly found out that a smart machine is more valuable and advantageous to use than one that’s a dim wit. The competition already afoot is robots vs. smart robots, the latter being preferred for intelligent automation and smart factories. Even a small SME with three or four cobots inhouse wants the edge that intelligence offers.

In 2018, China’s State Council issued the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan to vault China into being the “premier global AI innovation center” by 2030. The stated keys: “quantum information and quantum computing, intelligent manufacturing and robots.”

If China’s automation imperative is to strive to improve product and service quality, create greater throughput, enhance employee safety, reduce variability, and cut waste, with an overall impetus to increase productivity, then smart industrial robots are the advantaged assets.

Sooner than later, maybe much sooner than later, every robot manufactured, regardless of make, model or use, will carry a sticker, prominently displayed, that reads either “Pre-AI” or “Post-AI”.

Like automobiles without GPS, no one is going to want a “pre-AI” robot. Foreign manufacturers with smart industrial robots will be at a premium in China, until China develops its own.

“We have bridged the gap with outside players in terms of quality and technology,” said an executive from China’s Siasun in an interview with Nikkei Asian Review. In the same article, an executive at a key Japanese robot maker replied: “I can see from experience that Chinese players are steadily improving their abilities. There is still some difference in terms of technology, but we can’t let our guard down.”

With China’s vaunted AI/ML in development mode making smart industrial robots, that “difference’ may well be less than negligible very soon.