Investing in the Pain Points

Myanmar Awakening: New Automation Frontier

Forecast to nearly triple GDP by 2030: $69B to $200B

“Myanmar’s manufacturing sector reached a turning point in 2018 as liberalization, tax reforms, infrastructure improvements and the development of special economic zones helped turn the country from a low-cost regional production base to a rising manufacturing destination with capacity on the rise.”

—Oxford Business Group

Needy for everything, ready for anything

If there’s a Wild West in the ASEAN, it’s got to be Myanmar: rough-hewn, backward and downright dangerous, but beautiful, bountiful and brimming with promise.

Cut off from the world for fifty years, Myanmar’s “opening up” cranked back into play once again in 2011 with the surprising economic and political reforms of Thein Sein’s new government.

These days there’s a rush to get in on the country’s potential. With long borders on three sides with India, China, and Thailand, and a coastline with hundreds of miles of inland waterways that could make for an ideal transportation hub, Myanmar is central to a half billion nearby consumers who could easily become customers.

See related: Lucky Moon Over Myanmar

Don’t start counting industrial robots in Myanmar; there aren’t many. However, something well worth counting are the opportunities; places where a robot or two, maybe even a few cobots, could really do a lot for productivity and the bottom line.

PwC says of the recent arrivals: “Many foreign businesses are seeking a foothold in the country, in hopes that they may profit in the same way that some companies did with the economic rise of other emerging Asian nations. Huge projects are under way in infrastructure and power, led by investment from Japan, China, and Singapore.” $30 billion in foreign investments came in from the U.S. alone.

Fastest-growing economies

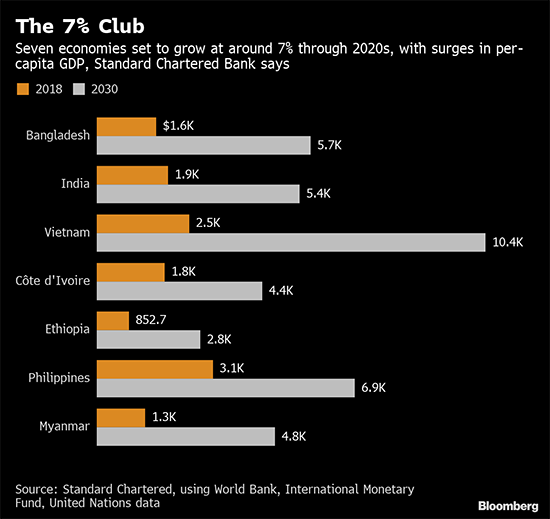

Nearly eight years on from Thein Sein’s reforms, Myanmar is starting to percolate, as this 2018-2030 chart The 7% Club (Standard Chartered) shows:

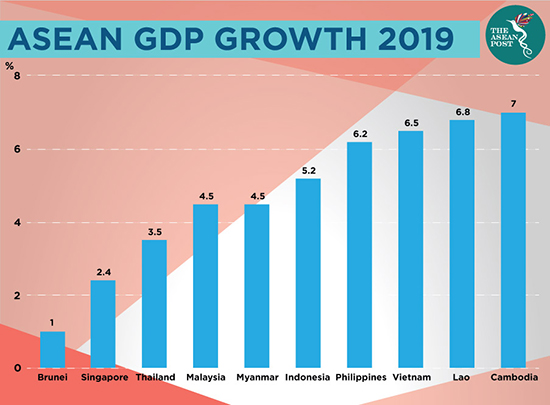

And although economic growth has slowed quite a bit from an eye-popping 8 percent in 2016, it’s still one of the fastest growing economies.

Euromonitor adds that the country’s consumer class will double by 2020. McKinsey forecasts its GDP to nearly triple by 2030. Good news; it seems things are on an upswing.

Coca-Cola is there, but like everyone else, runs the gauntlet of frequent power outages and delivery routes where only twenty percent of the roads are paved. And if the glacial progress of construction on three massive Special Economic Zones, Thilawa, Kyaukphyu, and Dawei, gets into gear, Myanmar could leap ahead with exports and jobs for thousands.

Although the massive infrastructure need (especially roads, bridges and power) is a whopping $300 billion, the rewards for investments are there aplenty. “Once the world’s leading rice exporter, Myanmar ranks 25th in the world for arable land, and the country’s per capita water endowment is 10 times that of China and India.

“Myanmar boasts 90 percent of the world’s jade, as well as rubies, sapphires, gold, tin, zinc, magnesium, copper, nickel, and old-growth teak forests that provide a source of timber. Gas production, aided by the construction of new pipelines crisscrossing the country, is expected to double.”

60 million sleepwalkers

The country’s 60 million citizens, 54 percent in agriculture (total of 22 million in the work force), are just awakening from dormancy. With 48,000 square miles of arable land (China has 517,000 square miles of arable land), Myanmar’s soil is rich but its farms are the least productive in the ASEAN. However, even a slight bit of automation on the journey from field to fork would be a dramatic improvement.

Although Myanmar is an agricultural-based economy, it is experiencing a manufacturing upside due to low wages (lowest per capita GDP in the ASEAN; see chart), duty-free exports to the EU and the United States, and strategic its location between China, India, and Thailand.

Manufacturing employs 2.3 million; textiles, clothing and footwear (TCF) employs 800,000. TCF monthly wages are lowest in the ASEAN $99; Vietnam $182; China $491.

“Myanmar is the third smallest TCF exporter, totaling $732 million, only about 2 percent of the ASEAN TCF export leader, Vietnam. Myanmar’s TCF exports, nevertheless, almost doubled in the last five years and accounted for 75 percent of total manufacturing exports in the country in 2015.

Meanwhile, around four to five factories are opening monthly in the garment sector. Last year, 65 new garment factories entered the market.

“Myanmar’s main export destination market is the European Union (EU) and Japan representing 45 percent and 28 percent of TCF export value in 2015, respectively.”

According to an Oxford Business Group report, Myanmar’s low labor benefits are considerable: “Verisk Maplecroft, a UK-based risk analysis consultancy, reporting in February 2015 that Myanmar’s labor costs are the second-lowest out of 172 countries surveyed, with only Djibouti ranking lower.”

Andrew Tan, a transplanted Singaporean (2012), and now principal at Invest Myanmar, sees Myanmar’s hobbling inefficiencies as prime opportunities for entrepreneurial modernization of almost any sort. “Find the pain points for consumers or business users,” he stresses, “in a country with 70 percent inefficiency everywhere, and the business opportunities are second to none.”

The Pun Effect

Serge Pun, the 65-year-old, Myanmar-born tycoon (Chinese descent, speaks Mandarin) is also bullish on the country’s future. As such, he’s brokering a $1.5 billion deal with state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), the state-owned builder that would involve “the construction of bridges, roads and other infrastructure west of the Yangon River for a new industrial zone aimed at attracting Chinese and other companies looking to relocate because of rising costs and the trade war with the US.”

Pun’s company, First Myanmar Investments, will remain neutral in the transaction, and Pun himself is offering his services on a pro bono basis.

As he told the Financial Times: “With or without the trade war, the movement has started: the search for places where you can have an abundance of labor, and at affordable prices.”

Myanmar’s answer to Shenzhen is how he describes it.

Despite a 2018 investment shortfall from the U.S. and Europe, investors in both are waiting to see a resolution to the Rohingya Muslim tragedy, according to Bloomberg Business, “strong capital inflows from Japan, China, South Korea and Singapore helped make Myanmar one of the strongest performing economies in Southeast Asia…the World Bank has forecast 7.2 percent growth over the medium term.”

A new Shenzhen on the Yangon River may well be a stretch, however, East Asia’s continuing quest for new markets, new consumers, and new resources—especially ones so close at hand—will undoubtedly draw more capital inflows and Foreign Direct Investment. That Myanmar is a prized route for China’s Belt and Road Initiative offers even more incentive and reassurance that the awakening country is relatively a safe bet.

Even more uplifting for investing in Myanmar would be if the recent buzz from Thailand about really, really digging the long-discussed Kra Canal happens in the near future.

See related: The Kra Canal Project

The Kra Canal would bring most of East Asia’s cargo traffic through the Gulf of Thailand and into the Indian Ocean, a parade of ships passing right in front of Myanmar’s front door.