Robot & Automation Paradise in the Making

Kra Canal Project: Often proposed, never attempted, the $32B project has now taken on special meaning

Opting for the Kra Canal and bypassing the Malacca Strait (500 nautical-mile-long waterway) would “save two to five days, cutting the cost of a 100,000-ton cargo ship voyage by about $300,000.” It’s reckoned that a Kra Canal would siphon off about 25 percent of the traffic now plying the Malacca Strait. And beef up container traffic at Thailand’s nearby, deep-sea port at Laem Chabang. Big winners: Thailand, China, Vietnam, Myanmar & India.

A trail for robots to follow

So what does a three-hundred-year old idea have to do with robotics and automation in Asia?

Plenty when that idea consists of building a canal to connect the Gulf of Thailand to the Andaman Sea. And with it, opening up a fast, direct, economical, and easily accessible trade route from Vietnam to Myanmar that has a combined population in excess of 250 million people, but also opens wide direct access to another billion-plus consumers from Bangladesh to India.

For many, it’s an idea whose time has come.

All of those Asian ports of call are surging economies where factories and warehouses will soon be built to meet rising consumer demands for just about everything. It’s a landscape anticipating factories large and small, and warehouses large and small, where automation and robots are inevitably bound, but as yet are rarities.

It’s a perfect scenario for a 5- to 10-year business plan for automation, which is the time frame that it will take to build the proposed $32 billion canal.

An old idea suddenly made new again

Bandied about for centuries the Kra Isthmus canal idea would probably remain in obscurity if not for China’s massive, continent-crossing One Belt, One Road project.

But lo, here it is again, and this time it’s serious with serious money from serious people. It makes all the difference when serious people see such an investment as the gateway to billions of dollars in spinoff opportunities.

King Narai of Siam was totally correct about the importance of such a canal when in 1677 he had the French engineer De Lamar scout the Kra Isthmus, the narrowest point on the Malay peninsula, where it’s a mere 27 miles from the Gulf of Thailand (South China Sea) to the Andaman Sea (Indian Ocean).

King Narai never moved on creating the canal; 17th century technology and the Kra’s imposing topography augured against the project. Over the centuries the Kra idea has come and slipped away countless times; the last in the late 1990s when Japan’s Global Infrastructure Fund (GIF) conducted a feasibility study, which estimated a cost of $20 billion.

Today’s return of the Kra big idea is to avoid the Malacca Strait—the world’s busiest trade route (84,000 ships a year)—750 miles to the south, where it’s narrow, super busy, piracy-prone and strategically sensitive.

Eighty percent of China’s 8.5 million barrel-a-day crude oil supply passes through the Strait at the mouth of Singapore’s harbor, the second largest container port in the world. If any foreign navy were to interdict Chinese trade (oil plus containers), China would be near helpless to remedy.

Hence, the reason why China is building a navy, including aircraft carriers, subs, and yes, islands in the South China Sea. In fact, Longhao, the Chinese construction company that built the Chinese government’s controversial bases in the South China Sea is among several builders lobbying the Thai government on the Kra Canal project.

It’s reckoned that a Kra Canal would siphon off about 25 percent of the traffic now plying the Malacca Strait.

Opting for the Kra Canal and bypassing the Malacca Strait (500 nautical-mile-long waterway) would “save two to five days, cutting the cost of a 100,000-ton cargo ship voyage by about $300,000.”

“The canal would also attract vessels too big to pass through the strait, which are presently forced to take much longer routes to and from East Asia via the Sunda or Lombok straits. Using the Kra Canal instead of the Lombok Strait would save 3,500km [2,175 miles] and six days’ sailing time.”

Ship owners might gladly pay canal transit fees in light of such savings realized from the shorter, faster route to the Indian Ocean or east into the South China Sea.

Most recently, the Thai-Chinese Cultural and Economic Association and the European Association for Business and Commerce “participated in a conference on the Kra Canal in Bangkok on September 2017 and a follow-up event on February 1, 2018, signaling a greater interest in executing the project.”

What next?

The Nikkei Asian Review reported on a possible plan in the works between Thai and Chinese interests agreeing on a joint study of the Kra Isthmus as a canal site.

“The specifics of the agreement are national secrets and I cannot give you details,” said a person in charge of the Chinese side…Reportedly, the plan is to build a canal 63 miles long, 1300 feet wide and 80 feet deep over 10 years.” Some see five years as an outside possibility.

According to a 2017 study from the Stockholm-based Institute for Security Policy, the Kra Canal would best serve China’s interests: “More than 30 percent of the world’s seaborne trade passes through this narrow 500 nautical-mile-long waterway [Malaaca Strait]. Apart from serving the strategic needs of the riparian states, China, Japan, and South Korea are reliant on this strategic waterway for their supplies, especially energy.

“Having little control over the passage, any disruption – ranging from piracy to fears of a potential naval blockade by the United States and its allies – will have an adverse impact on China’s long-term food and energy security.”

Seems that it is in the best interests of China to ensure, a/k/a finance, the Kra Canal finally gets built.

Along for the ride

Tagging along with this geopolitical Sino fear is a ton of potential economic prosperity for Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar in the form of infrastructure, new trading routes, manufacturing output, and easier access to consumers.

Such prosperity, if equitably distributed, might even have a calming effect on tensions in some of Myanmar’s violence-buffeted regions. A good job with fair wages can work wonders with the disaffected.

See related: Lucky Moon Over Myanmar

Robot destiny

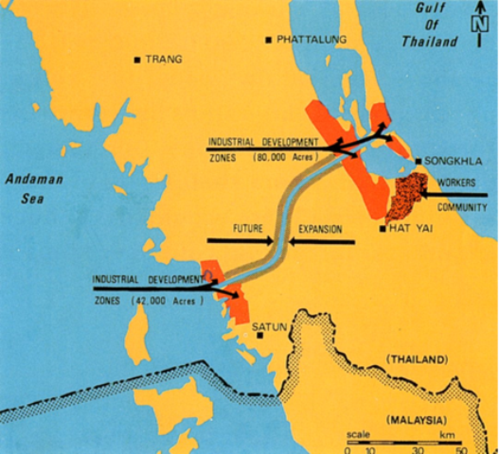

A Thai promotional publication is promising special economic zones to accompany the canal’s construction. Funds for infrastructure, including new cities, industries, and even artificial offshore islands built with excavated earth.

“The combined project would eventually create some 2.5 million jobs according to the promotional book — enough to employ one in four of the roughly 10 million inhabitants of southern Thailand.”

Whatever the eventual outcome, the power of a major construction project to spawn the possibility of economic benefits is a great motivator. No canal means life as usual, which for many means no future.

Thailand is not alone, there’s a potential $8.6 billion Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ) on the Myanmar side of the Kra Canal.

And if all of this future comes to pass, it’s easy to see the footsteps of robots moving in to automate much of the proposed industry.