Will Current 5-Year Plan Be China's Greatest Ever?

If so, somewhere prominent will reside a massive statue of an industrial robot covered in lotus flowers and orchids…and gawked at by schoolchildren

Two down three to go

Come the year 2020, China may well look back upon its current 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) as its greatest achievement of the last half century. Maybe even hailed as the most successful Five-Year Plan ever, one that finally catapults both the country and its people into a trajectory of long-term prosperity and world leadership.

See related: China’s Big Push: Xi, Robots and Productivity

If that comes to pass—and it looks like China has a more than reasonable chance of pulling it off—then lots of praise and thanks will be heaped upon the hard-working armies of industrial robots that China had the wisdom to call into action on its behalf.

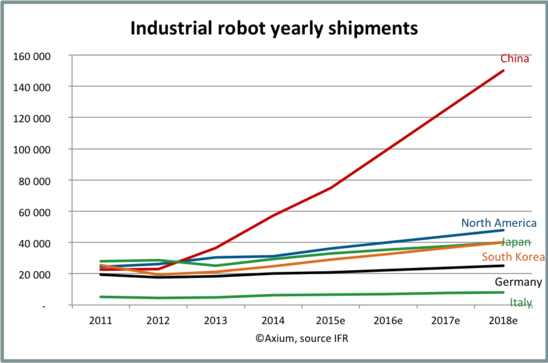

Already the largest market for industrial robots in the world (87,000 in 2016), China’s taste for these tireless and efficient workers is forecast to skyrocket.

See related: Asian Outlook 2017: Robots, Automation & Industry

Without hesitation or reservation, China’s new Five-Year Plan has made a bold commitment for its industrial robots to help it achieve a huge, new goal— productivity—which Caixin Online calls “a first for modern China”.

Authoring the piece for Caixin is Yale’s Stephen Roach, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia. “The stated goal is to boost per capita labor productivity (i.e., output per worker) in so-called advanced industries (high-end manufacturing, modern services, and strategic and emerging industries)… to a 38 percent increase over the five-year planning period, or roughly a 7 percent average annual rate of labor productivity growth in this key segment of the economy.

“That would be a spectacular result, by any standards – if, of course, it can be achieved,” concludes Roach.

Such a 38 percent goal can’t be achieved without massive automation taking place in the country’s key industries of “high-end manufacturing, modern services, and strategic and emerging industries”.

Without a robot intervention of epic proportions, general automation as well as those lofty productivity numbers are an impossible dream. Hence, the commitment to robotics very high up in the new Five-Year Plan.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, China’s top economic official, hoisted robotics way up the list of must-haves for the new Five-Year Plan, which means king-size investments and emperor-size expectations for the technology.

The differences between China’s 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015)and its 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) are like night and day.

The China of the 12th Five-Year Plan was high flying, basking in the glow of nearly a decade of 10 percent annual GDP growth ($11 trillion in 2015), a rambunctious stock market, with exports incessantly cascading from seven of the world’s ten busiest seaports; China was a surging giant challenging the dominance of the U.S. and its $17 trillion in GDP.

Robots barely squeaked onto the 12th Five-Year Plan—appearing for the very first time in all the previous sixty years of China’s Five-Year Plans—barely noticeable, wedged in with automated factory machinery.

Times have changed

The China of the 13th Five-Year Plan finds itself stumbling with exports, reeling from the implosion of its vaunted stock market, its currency in jeopardy, and a worried populace.

As Caixin artfully sums it all up: “The result is an increasingly powerful negative feedback loop – with China’s problems leading to global concerns, which then exacerbate the angst over an externally dependent Chinese economy.”

China’s “epic robot intervention” is well underway.

With 100k industrial robots purchased in 2017, China become the world’s leading mega-buyer of industrial robots, rising 55 percent year on year and accounting for a quarter of the world’s total.

The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) forecasts worldwide sales of industrial robots at 400,000 by 2018, with China buying 35 percent of them.

According to Grand View Research, the global industrial robotics market is forecast to exceed $40 billion by 2020 ($25.7 billion in 2013).

Key for China in the purchase of 140,000 industrial robots annually is that the percentage produced by China’s indigenous robot industry is on the rise.

“Foreign robots occupy the main market,” noted Zhou Shuopeng, vice general manager at Shanghai STEP Robotics. “In China, foreign robot suppliers increased their sales by 47 percent to about 40,000 units, accounting for a share of 71 percent of the whole Chinese market. Domestic robot suppliers increased their sales by 76.6 percent to about 16,000 units, only accounting for a share of 29 percent.”

See related:The Guru of Shanghai: Domestic Robots on the Rise

Worrisome to Japan’s industrial robot manufacturers, most of whom have joint manufacturing facilities in China, is that the Nikkei Asian Review reports that current estimates put China’s domestic robot industry supplying up to 45 percent, nearly doubling, in a mere two years (2016-2018).

With an estimated 250,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China where all procurements are either directed by or, at minimum, strongly influenced by the state, the 45 percent increase in domestic robot purchases will be easy to attain. More is more like it.

Where the robots are bound

Most of China’s robots are headed for the cities on the coast where aging worker populations, high wages, and sagging productivity are putting a drag on both competitiveness, quality and speed of manufacturing.

Provinces like Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, and Zhejiang, (See: MAPS) each with annual GDPs of $1 trillion or more and each with tens of thousands of old-line factories— Guangdong alone has over 60,000—will, quite logically, get first preference.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has taken up the challenge to make significant progress by 2020.

For example, Guangdong has put up $146 billionto replace worker and labor shortages and to spur innovation and productivity as it transitions from capital-intensive manufacturing to labor-intensive services.

In Dongguan, an industrial city in central Guangdong province, over 60 percent of industrial enterprises have reportedly begun replacing humans with robots, while in Foshan the government said the value of the city’s automation and robotics market would reach $46.5 billion in five years.

Meanwhile, the government of Zhejiang province said it would invest $124 billion to push its 36,000 manufacturers to replace human labor with robots in five years.

When the robots settle in to take on jobs formerly performed by people, millions of jobs will be lost in the process. Over the next three years it is estimated that upwards ofsix million workers will lose their jobs. The government expects to pay billions of dollars to displaced workers.

A similar retrenchment program resulting from “a restructuring of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) from 1998 to 2003 led to around 28 million jobs lost, and cost the central government about $11.3 billion in resettlement funds.”

Yin Weimin, the minister for human resources and social security, said China expects to lay off 1.8 million workers in the coal and steel industries. But he did not give a timeframe.

The government also claims that the country will create 10 million new jobs.

Game on!

Years from now, decades even, millions of Chinese, both technologists and common citizens, may well look back at 2016 to 2020 and see it as their finest hour. Nation-building veterans who played a role in making the 13th Five-Year Plan the best ever.

And in major cities along the coast there will be a plaza or square where the honored statues of industrial robots will stand, without which the 13th Five-Year Plan would not have been half as grand… or grand at all.