It's Just a Matter of Time...

E-Commerce at Work: Humans Beware

The churn in e-commerce warehouses is challenging humans to keep pace. Can they for very long?

Rehearsal for When the Machines Take Over

It’s a bizarre twilight time these days when more than ever

warehouse workers are being hired by the tens of thousands, yet their work is being monitored

as if they were already robots; just flesh and blood robots.

“In pursuit of squeezing evermore productivity from e-commerce warehouses, the quality of work for humans has begun to change…for the worse, says Beth Gutelius. Her report speaks about body sensors, and AI-powered management systems that are pressuring for harder, faster, work shifts that are filled with ever-increasing levels of scrutiny from supervisors. What some are calling Digital Taylorism!”

It’s just a matter of time…

There’s recent data, albeit in its very earliest stages, that’s showing us how, why, and where automation will finally push humans out of warehouses forever. The exact timing of just when is still a bit amorphous, but 5 to 10 years (in North America) is the odds-on guess.

Sometime around 2026 logistics tech will start to squeeze out the carbon life forms in warehouses, especially e-commerce warehouses (i.e. those specializing in fulfilling online orders) as opposed to traditional warehouses for big-box items, pallet loads, and the like.

This potential endgame scenario comes from a couple of University of Illinois at Chicago professors, Beth Gutelius from the school’s Center for Urban Economic Development and Nik Theodore from the school’s Great Cities Institute. Gutelius and Theodore have put together an incisive, very well-written, and exhaustive 75-page study/survey titled, The Future of Warehouse Work: Technological Change in the U.S. Logistics Industry.

The Gutelius-Theodore research is not a sad tale; it’s just an inevitable one. Although much of the media reporting on their research settles in on human safety and the rise in accidents in automated warehouses, dig a little deeper and another thread emerges; one that shows what’s waiting for humans when they try to vie with AI-powered logistics robots. It’s not pretty.

It’s all about business

The number and speed of brown boxes cascading through e-commerce warehouses is cranking up exponentially. As the pace of online orders increases, package throughput will increase to meet demand, which means the working speed of logistics robots will need to be increased accordingly. It’s just the logical reflex reaction that industry takes to meet demand.

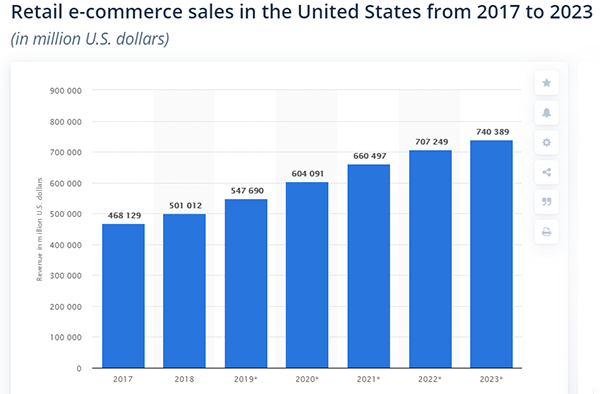

“In 2018, U.S. online retail sales of physical goods amounted to $501 billion and are projected to surpass $740 billion by 2023.”

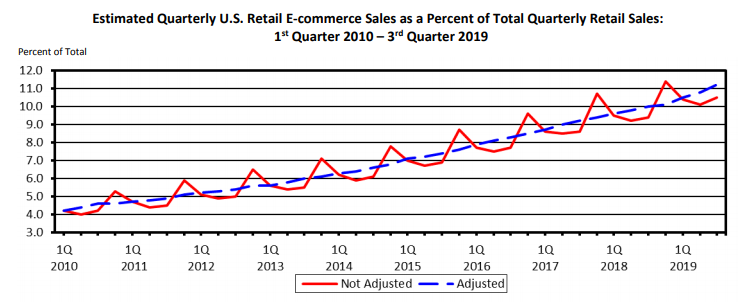

The churn in e-commerce warehouses is sharply increasing as shown in this chart (U.S. Department of Labor):

Impacting that churn with additional warehouse volatility is M-commerce—retail purchases made on mobile phones—which has been the fastest-growing shopping channel of the past five years (up by 522 percent between 2012 and 2017). “M-commerce is forecast to grow by nearly 50 percent annually between 2018 and 2022, as consumers grow more attached to their phones and retailers invest in mobile platforms.”

E-commerce sales, driven more and more by M-commerce, present a future combination that will create an uneven collaboration between logistics robots and humans that will sooner rather than later reach a breaking point. Even now the dark shadow of excessive churn is beginning to manifest itself in e-commerce warehouses.

In pursuit of squeezing evermore productivity from e-commerce warehouses, the quality of work for humans has begun to change…for the worse, says Gutelius. Her report speaks about body sensors, and AI-powered management systems that are pressuring for harder, faster, work shifts that are filled with ever-increasing levels of scrutiny from supervisors. What some are calling Digital Taylorism!

For example, “algorithmic warehouse management systems on the backend that ‘track, analyze, and inform workers about their performance’ in real time, measuring them against their colleagues and setting more aggressive goals. The unprecedented granularity of this data has the potential to pressure workers to perform tasks more quickly.”

“The next decade is a story not about job loss, but more so about changes in job quality,” writes Gutelius in her report. She and Theodore believe: “Technology has led to workers being pushed harder and also their privacy getting violated.” In effect, for many, technology is making a bad job worse.

The hope is that humans can keep pace with the work velocity that’s increasing everywhere around them. In our collective heart of hearts, however, we all know that humans won’t keep up and that it’s a just a matter of time.

Workers and their warehouses in the U.S

And what of the warehouses themselves, most of which in the U.S. are small and cannot afford high-tech upgrades or makeovers…most of which would also find it difficult to support even RaaS (Robots as a Service)? E-commerce churn could well exact a severe toll on the viability of many of those warehouses.

In the U.S., there are approximately 1 million workers who collectively earn wages approaching $50 billion annually [median hourly wage $15.85]. “According to County Business Patterns (2016), there are just more than 15,000 warehousing establishments in the United States, the majority of which are small, employing fewer than 20 workers. However, while establishments with 100 or more workers account for just 12 percent of total establishments, they account for the lion’s share of employment—73 percent of all warehouse workers work in these facilities.” For example, Amazon’s warehouse archipelago with 250,000 workers, or the Inland Empire in California employing 68,000.

Because of razor-thin profit margins and cost-sensitive competition from other warehouses, “warehouse operators have thus far moved cautiously into risky experiments with new technologies, relying instead on streamlining current processes and on workforce experimentation.”

Mega shippers like Amazon, DHL, XPO, and now Shopify have the wherewithal to spend on logistics robots. Amazon owns 200,000 robots, and its own robot factory (Amazon Robotics (formerly Kiva Robotics)) to experiment with and to build them.

It creates an atmosphere for disruption through consolidation, as PwC’s The Future of the Logistics Industry remarks: “The current market leaders compete for a dominant market position by acquiring smaller players, achieving scale through consolidation, and innovation through the acquisition of smaller entrepreneurial start-ups.”

Gutelius and Theodore offer up this chilling viewpoint: “For all the emphasis on sophisticated, strategic approaches to goods movement that abound in business literature, warehousing largely still is seen as a cost to be contained—a “necessary evil.”

“Warehousing rarely adds an increment of value to the end product—and fast, free shipping and returns reinforce this point—so the dominant dynamic across the warehousing industry is one of low margins and cost cutting.”

So, where in this “necessary evil” do humans sit? Not very high, that’s for sure.

In stacking up myriad concerns over humans laboring in logistics, e-commerce warehouses are quickly forcing the realization that humans just don’t belong there; they simply aren’t good places for humans to be. The job is totally unrewarding to the workers, the pay is low, human workers are constantly surveilled by sensors and their job performance graded by algorithms. Clearly, humans are just being tolerated until logistics robots shed their clumsiness and get a bit brainier, which is not far off.

Then what? The throughput speed in warehouses will be ratcheted way up to meet the demands of the marketplace. Humans who can’t keep up in 2021 surely will be overwhelmed a few years on.

E-commerce warehouses have also forced another and even weightier realization: What’s to be done with a million warehouse workers when they are no longer needed?