Should All Humanoids

Be Created Equal?

If the intended job for a humanoid robot is menial or worse, should the robot’s components, skill set, and intelligence match that of the required task, and no more? Or should every humanoid be built as advanced as possible regardless of intended use?

Reading that Chinese electric vehicle (EV) makers like BYD, Nio, and Xpeng are building their own humanoid robots in-house, with BYD’s GoMate (in partnership with China’s GAC Motor) scheduled to “install wires in cars” on its production line, got me to thinking about just how intelligent and physically robust a humanoid needs to be to perform such a task.

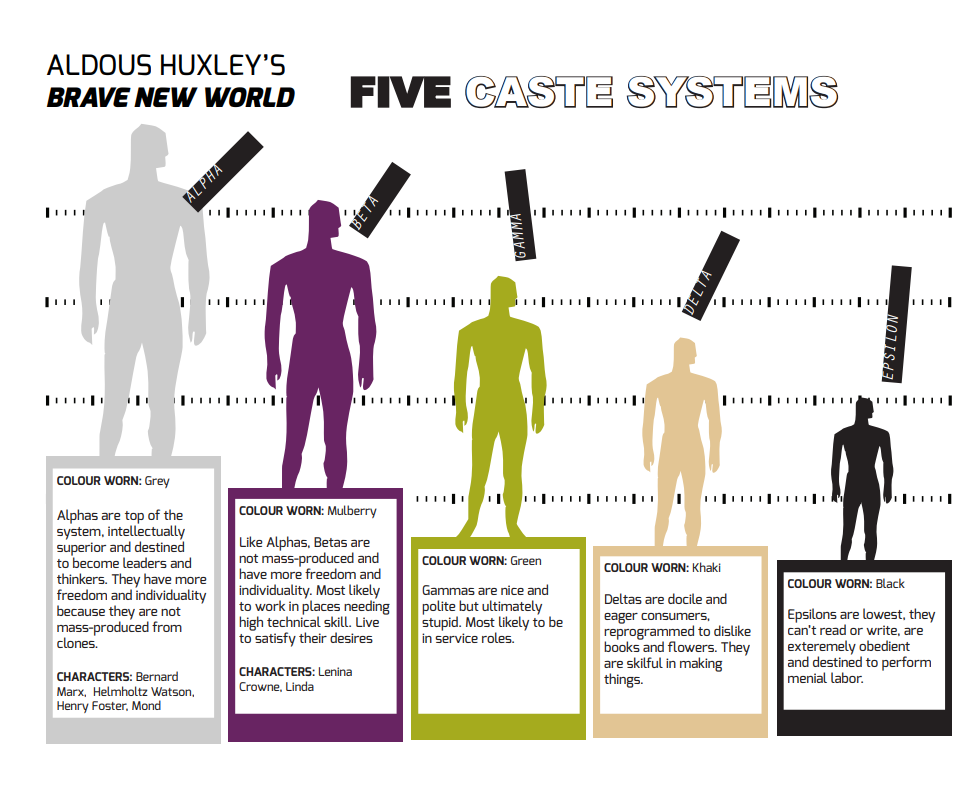

By extension, will the future present us with a humanoid robot caste system somewhat akin to that in Huxley’s Brave New World for humans: Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas, and Epsilons? Alphas and Betas are trained (er, conditioned) to be the caste’s upper echelons, while Epsilons, the lowest caste members, have very little cognitive ability, and as such, are tasked with jobs such as sewage workers.

The thought here being, will we expensively over-engineer the intelligence of a humanoid that’s bound for a robot life in the salt mines? Berkeley’s recent RoVi-Aug is billed as the future of robot skill transfer because it eliminates the need for human intervention in the learning process, simplifying robotic training. However, even with a zero-shot pipeline of transfer learning (from simulation to real world), is it wasted on a humanoid epsilon? Shouldn’t the brain and brawn of a humanoid match its intended life tasks?

It would seem that not all humanoid robots need to be created equal because different robots might serve different purposes. Common sense would indicate that the purpose and function of the robot should dictate the level of intelligence required. Some robots might be designed for simple, repetitive tasks that don’t require advanced cognitive abilities, while others might be built to interact with humans in more complex and dynamic environments, necessitating higher intelligence.

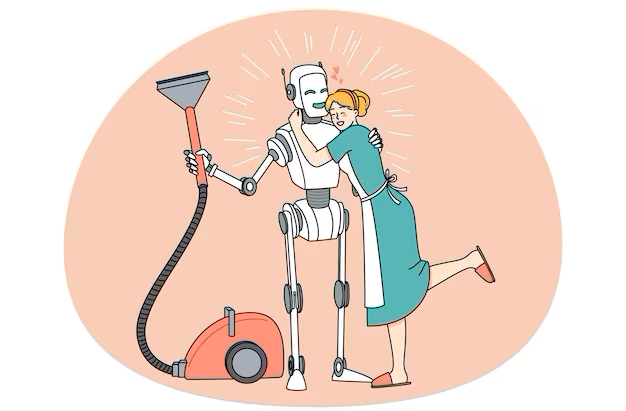

For instance, a robot designed with simple household chores in mind might not need advanced emotional intelligence, however, one designed for healthcare support may require empathy, decision-making, and adaptability, which demands more advanced cognition. The level of intelligence and autonomy a humanoid robot possesses should be tailored to its specific role in society or the workplace. What then? Is the future of humanoids bound for a world similar to Huxley’s human caste system?

Point to ponder: What if the human in the household is a total dummy and constantly belittled by an on-the-ball humanoid? That’s definitely a clash that probably won’t end well. Maybe the robot will need a dial on its head to tone down snarkiness. Alternately, a humanoid in Elon Musk’s home might be ill-prepared about everything coming from the daddy of Optimus.

Should intelligence then be context-dependent?

While some tasks, like customer service or healthcare, may benefit from advanced artificial intelligence (AI), other tasks like delivering goods or simple manufacturing might not require the same cognitive abilities.

In fact, creating all robots with the same level of intelligence could be inefficient and unnecessarily costly. It would also potentially lead to issues with over-engineering robots for simple tasks, which would increase their complexity, cost, and risk of malfunction without significant benefit.

Scenarios where a less intelligent humanoid robot might be preferred:

- Cost-effectiveness: Robots with simpler designs and lower intelligence are generally cheaper to manufacture, maintain, and operate. For tasks that do not require high levels of intelligence, it’s more economical to choose a less advanced model.

- Task simplicity: Many tasks, such as cleaning, transportation, or basic data entry, don’t require advanced problem-solving skills. A robot designed for these tasks might perform just as well with limited intelligence, as long as it is reliable and efficient.

- Safety and control: In environments where the risk of unexpected behavior must be minimized, less intelligent robots can be more predictable and safer. For example, robots in high-risk environments (like manufacturing or hazardous material handling) might only need to follow basic instructions and not engage in autonomous decision-making.

- Specificity of function: In some cases, a less intelligent robot could be better suited because it is designed for a very specific, repetitive task. These robots would be optimized to perform a single job efficiently, without the need for complex processing.

The flip side

There are some clear benefits to making humanoid robots intelligent, particularly in contexts where they interact with humans in dynamic, unpredictable environments.

Intelligent humanoid robots can:

- Adapt to different situations: They could handle a wide range of tasks and adapt to varying needs or challenges in real time.

- Enhance human-robot interaction: More intelligent robots could better understand human emotions, make nuanced decisions, and build rapport with people, making them more effective in social or caregiving roles.

- Increase efficiency: Intelligent robots can learn and optimize their own behaviors, improving productivity and problem-solving skills.

However, these benefits are not universal. In many cases, more basic or specialized robots can be more efficient and safer than trying to make them highly intelligent in every situation.

Case in point, my mildly retarded cousin Richie. A very aware, intelligent, and persuasive humanoid robot would rule his odd household in a heartbeat. That could be a big problem.

So, the question remains: Should all humanoids be created equal?

Got a solid reply? We’ll publish it. Send it along: founder@asianroboticsreview.com