Delayed since New Year's Eve!

OFT-DELAYED Law 144 Goes Live!

When New York City’s controversial AI bias audit law was set to take effect on January 1, 2023, confusion reigned about its details and delay seemed inevitable

Delayed from New Year's Eve 2023 until July 5th

The Wait Is Over for Law 144!

The adoption of AI and automation is becoming ubiquitous across sectors, but particularly in the HR sector, where AI-driven and automated tools are increasingly being used in talent management across the employee lifecycle. From evaluating candidates to performance tracking to onboarding, HR professionals are capitalising on the benefits of these tools to increase efficiency, improve candidate experience, and save money. However, with the applications of these tools come risks, such as existing biases being perpetuated and amplified, novel sources of bias, and a lack of transparency about the system’s capabilities and limitations.

What Is Local Law 144?

Due to increasing concerns about the risks of using automated tools to make employment decisions, the New York City Council took decisive action, passing a landmark piece of legislation in 2021 known as the Bias Audit Law. This law – Local Law 144 – is set to be enforced from 5 July 2023, after first being pushed back to 15 April 2023 from its initial enforcement date of 1 January 2023.

This delay was due to rules being proposed by New York City’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) to clarify the requirements of the law and supports its implementation enforcement. The first set of proposed rules were published in September 2022 and a public hearing was held on them in November 2022. Due to numerous concerns raised about the effectiveness of these rules, the DCWP then postponed the enforcement date to 15 April 2023 in December 2022 before publishing a second version of the proposed rules shortly after.

Another public hearing was then held on the second version of the rules in January 2023 and the DCWP issued an update in February 2023 stating that it was still working for the large volume of comments. Finally, on 6 April 2023, the DCWP adopted its final version of the rules and announced a final enforcement date of 5 July 2023. In this blog post, we give an overview of the key elements of the rules that have evolved throughout this rulemaking process. MORE

by Henry Lenard

The first-of-its-kind law requires employers doing business in New York City to conduct annual independent bias audits of automated employment decision tools (AEDT) used in the hiring and employee promotion process. It is expected to have nationwide implications.

“State and local governments are moving quickly to enact laws affecting the use of AI in employment decisions. New York City is the poster child for such legislation because of its size and potential scope,” said James A. Paretti, Jr., a shareholder in Littler’s Washington, D.C. office who has been closely following this issue.

Littler is the world’s largest employment and labor law practice representing management and held its inaugural Artificial Intelligence Summit this past September in Washington, D.C.

According to Paretti, artificial intelligence is reinventing human resources, and HR is preparing to embrace AI tools without knowing exactly what they will deliver or change.

“For many companies, the first pilots of AI are in talent acquisition because they can see significant, measurable and immediate results,” said Paretti.

New York City Local Law 144 bars employers and employment agencies from using AEDTs for the screening of job applicants or employee promotions unless those tools have been independently audited for bias no more than one year prior to its use. Thus, employers wishing to continue or begin using AEDTs in January should have begun conducting their bias audits at the beginning of this year.

A summary of that audit must be made publicly available on the company or employment agency’s website, as well as the distribution date of the AEDT.

In addition, the law requires that employers or employment agencies provide notice to job candidates no less than 10 business days before using an AEDT that such a tool will be deployed for reviewing their application.

Employers and agencies must also specify what job qualifications and characteristics will be used. The individual has the right to request an alternative selection process, such as a personal interview. The law establishes civil penalties of $500 to $1,500 for each violation of any of these requirements.

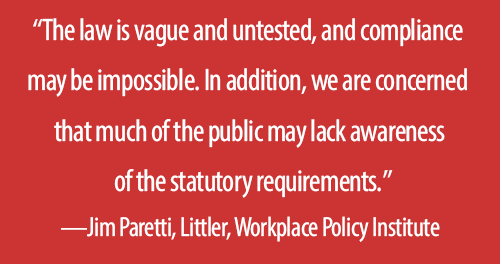

“The law is vague and untested, and compliance may be impossible. In addition, we are concerned that much of the public may lack awareness of the statutory requirements,” said Paretti.

The proposed regulations published by the DCWP:

- Define and limit the scope of the “substantially assist or replace” standard for the applicability of automated employment decision tools (AEDTs), making it clear that an AEDT is covered under the law where it is used as a dispositive decision criterion or to modify a conclusion derived from other factors, including human decision-making.

- Clarify that a “candidate for employment” means an individual who has applied for a specific employment position and has provided necessary information, such as a resume or application form. This appears to be intended to limit the application of the law to candidates who may have been considered in a search but have not expressed interest in or applied for a given job.

- Add significant detail on the structure and content of the bias audit required by the law, including requirements that employers calculate the selection rate of an artificial intelligence tool based on race, ethnicity, and gender, and an impact ratio of the tool’s operation on these categories.

- Expand on the content of the audit summary that employers are required to publish, which includes a requirement that the selection rate and impact ratio of an artificial intelligence tool be required in the summary.

- Provide alternatives for complying with the notice requirement of the law, including by way of mail or email, notice on the careers section of an employer’s website, or via a notice included in a job listing.

Last month the New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) proposed additional rules relating to the law, which Paretti said provides “much-needed clarity on key gaps with Local Law 144, although significant concerns remain.”

An AEDT uses machine learning, statistical modeling, data analytics or artificial intelligence to screen job applicants. It generates a simplified output such as a score, classification or recommendation to assist or replace discretionary decision-making. The bias audit is intended to analyze the AEDT for possible discrimination against candidates by race or gender.

According to the Society of Human Resource Management, the world’s largest HR group, 49 percent of its member companies currently use artificial intelligence for recruiting and hiring. Hiring managers leverage AI-supported products to find more candidates, schedule interviews faster and make more informed hires.

SHRM has more than 575 chapters globally, with more than 300,000 members in 165 countries.

The increased use of AEDTs is primarily because of its cost effectiveness. A study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research compared hires made by an AEDT to those made by hiring managers. It found a roughly 15 percent higher retention rate when algorithms made the decisions.

That is important because according to California-based career consultant Zippia, the average cost per hire in the United States is $4,700 and it can take 36 to 42 days to fill a position. On average, a HR department allocates 15 percent of its budget toward recruitment efforts.

It costs up to 40 percent of an employee’s base salary to hire a new employee with benefits, meaning it can take up to six months for a company to make up the money it spent on a new hire. Zippia reports that 63 percent of hiring managers and talent acquisition specialists say AI has positively changed recruiting is handled at their company.

That said, Littler’s Paretti said that vendor due diligence is a must, and legal and HR professionals need to be assigned to vet employment applications.

“To the extent possible, companies should avoid completely replacing discretion with algorithms wholesale,” Paretti said. “The importance of human review is critical, particularly where that review has the potential to change the decision.”

In the wake of the pending New York City AI bias audit law, Paretti said companies need also to ensure the data from which the algorithm learns is free of bias.

“You must remember that while attorney-client privilege in an audit is critical, the underlying data is rarely protected,” said Paretti.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE: MAY 2022

Nationwide Implications for New York City’s AI Bias Audit Law

Can machine learning, statistical modeling, and data analytics combine to fairly screen job applicants?