Reclaiming China

Xi Jinping, “Faust” & Robots

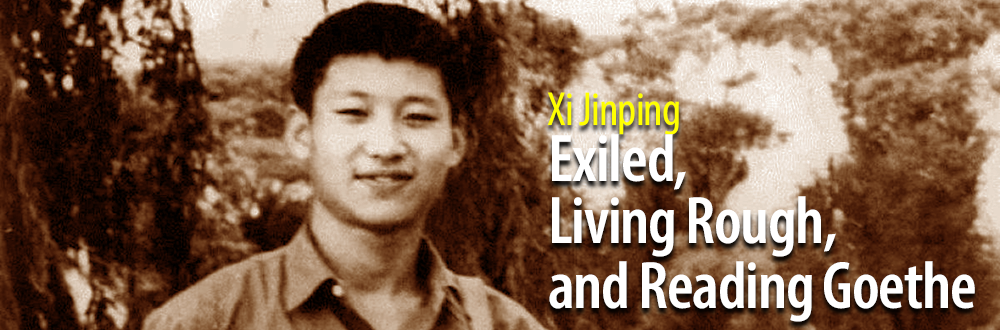

Exiled, Living Rough, and Reading Goethe

“There are but two roads that lead to an important goal and to the doing of great things:

strength and perseverance.” —Goethe’s Faust

“Reclaiming” China

Angela Merkel was said to be pleased and impressed when China’s Xi Jinping casually rambled off lines from Goethe’s Faust. Seems Xi has the Chinese translation (by Guo Moruo) of the German masterpiece memorized.

As a teenager Xi was given a copy of Faust by a fellow exile when both boys got caught up in China’s Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement, whereby “educated, urban youngsters were forced to live in rural China ‘to learn from the people’.” Xi’s rural outpost was “Liangjiahe, a miserably poor mountain village of windowless cave houses in a barren landscape of deforested hills in northern Shaanxi.” Xi, as a 15-year-old from a comfy home in Beijing’s Zhongnanhai leadership compound, suddenly found himself with a cave for a home. That cave is today a museum visited by tens of thousands annually.

Young Xi read and re-read, and eventually memorized, Goethe’s tale of Faust and his battle with the devil, of his evading damnation and finding redemption.

Amazon’s recommendations claim that Goethe’s Faust is “frequently bought together” with Dante’s Divine Comedy and Milton’s Paradise Lost. A weighty trio, to say the least. And plenty weighty for an impressionable Chinese teenager trying to make sense of what had just happened to his life.

Amazon’s recommendations claim that Goethe’s Faust is “frequently bought together” with Dante’s Divine Comedy and Milton’s Paradise Lost. A weighty trio, to say the least. And plenty weighty for an impressionable Chinese teenager trying to make sense of what had just happened to his life.

Bravo to the German-to-Mandarin translator (Guo Moruo) who took on this monster; Goethe’s working vocabulary was 93,000 words—reputed to be the world’s largest. He used every one of them in writing Faust, which I can personally attest to. My German class labored through a reading aus dem Deutschen, during which my Langenscheidt’s dictionary was torn to shreds.

Much later, Xi Jinping, in a TV interview in 2004, said that “he experienced his political awakening when he was ‘sent down’ to Liangjiahe.” “Many ideas and characteristics of mine were formed [in Liangjiahe].”

Was Faust part of that awakening, ideas and characteristics? Threads of them are visible today in China with Xi’s push to accelerated modernization, automation, even robotics; the spirit of which, amazingly, are all there in Faust’s enormous undertaking of reclaiming land from the sea.

Transformation and renewal

“There are but two roads that lead to an important goal and to the doing of great things: strength and perseverance.” —Goethe’s Faust

Sounds like something Xi Jinping would put in a speech, doesn’t it?

Here it is as young Xi might have encountered it:

通往重要目标和成就伟大事业的道路只有两条:力量和毅力

Faust was applying “strength and perseverance” in attempting to do the near impossible in reclaiming land from the sea; it’s usually, especially with climate change, the other way around: the sea irretrievably gobbles up land, unless you’re Dutch.

It’s something that Goethe knew a lot about. At 26, Goethe became a minister under Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. His tasks included overseeing the mining industry and managing the bureaus for road-building.

“The action of Faust reclaiming land from the sea–dredging canals, building dikes–taking land from the sea and adding it to the land mass” was familiar to Goethe. “In this process Faust finds great contentment. Just before his death, Faust steps back from his labors and sees a utopian vision of a noble band of people inhabiting his newly claimed land.”

Belt & Road, Industry 4.0, even the last two Five-Year Plans, seem cut from the same cloth as the grandeur of Goethe’s vision of transformation and renewal. And robots, quite simply, are the great enablers of China’s transformation. Probably why China has been by far the world’s largest buyer of robots since 2013; the same year that Xi took office.

In a larger sense, it might be said that Xi is continuing the process of “reclaiming” China from obscurity; what Deng Xiaoping had begun forty years previous. An obscurity thrust upon China’s world-leading economy by the disastrous Treaties of Tianjin (1858), and the country’s ensuing national descent, which China calls the Hundred Years of Humiliation (1839-1949).

Xi’s reclamation helper: Liu He

Like-minded in his reclamation plan is Xi’s close friend, colleague, and economic czar, Liu He, who the world knows as a Vice Premier of the People’s Republic of China, and top trade negotiator for the China–United States trade war. And since 2018, has led the country’s technology reform task force.

He has published widely on macroeconomics, Chinese industrial and economic development policy, new economic theory and the information industry. He worked successively for the National Planning Commission, the State Information Center, and the Development Research Center of the State Council.

He has published widely on macroeconomics, Chinese industrial and economic development policy, new economic theory and the information industry. He worked successively for the National Planning Commission, the State Information Center, and the Development Research Center of the State Council.

And Uncle He, as the 69-year-old economist is known, was reportedly a Xi schoolboy friend, which is even best when it comes to trust and power.

Curiously, Uncle He has great admiration for Nobel Prize-winning economist Edmund Phelps; there’s a direct line of economic thinking shared between Phelps and He, and also, with Xi Jinping’s vision of a prosperous China.

Curiously, Uncle He has great admiration for Nobel Prize-winning economist Edmund Phelps; there’s a direct line of economic thinking shared between Phelps and He, and also, with Xi Jinping’s vision of a prosperous China.

Phelps’ book Mass Flourishing, which is a best seller China, makes the case that the wellspring of this flourishing was modern values such as the desire to create, explore, and meet challenges. “These values fueled the grassroots dynamism that was necessary for widespread, indigenous innovation. Most innovation wasn’t driven by a few isolated visionaries like Henry Ford and Steve Jobs; rather, it was driven by millions of people empowered to think of, develop, and market innumerable new products and processes, and improvements to existing ones. Mass flourishing — a combination of material well-being and the ‘good life’ in a broader sense — was created by this mass innovation.”

That Phelpsian idea of mass innovation, the “Created in China” rather than “Made in China” is the country’s next big hurdle. The subtitle from Mass Flourishing, How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change, is that hurdle. And all of it has a distinct echo coming from Goethe, when he has Faust “step back from his labors to see a utopian vision of a noble band of people inhabiting his newly claimed land.”

“14,000 new companies are registered daily in China since the country took the initiative to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation in 2014,” which was Xi’s second year in office.

And as Xi Jinping said in his 2004 TV interview: “Many ideas and characteristics of mine were formed [in Liangjiahe].” Then just maybe, Geothe played a part in helping the teenage Xi to form some of them.

Sure looks that way.