Post-COVID: New Automation, New Attitude, New Asia

Factory boom: Asia spending big and fast for technological advantage is making headway

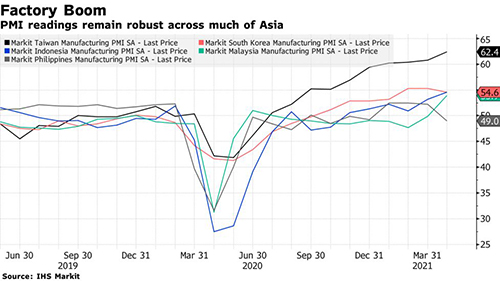

Factory Boom in Asia: PMI Readings Robust Across the Continent —Bloomberg

Asian Potential: China, Thailand and Indonesia —Wonsik Choi, McKinsey

Reinvigorating Japan’s Lagging Industrial R&D —McKinsey

Factory Asia booming

Asia’s manufacturing activity remained robust through April even as a gauge of factory output in China, the region’s top economy and industrial powerhouse, showed signs of cooling.

Taiwan’s IHS Markit April manufacturing purchasing managers’ index rose to 62.4 from 60.8 in March, its highest reading since March 2010. New orders also reached their highest level since the same month.

Taiwan’s IHS Markit April manufacturing purchasing managers’ index rose to 62.4 from 60.8 in March, its highest reading since March 2010. New orders also reached their highest level since the same month.

South Korea’s IHS Markit PMI index for April slipped to 54.6 from 55.3 but remains well above the 50 level, signaling ongoing expansion. It was the seventh straight month of expansion for the South Korean gauge, a first in almost a decade.

South Korean exports last month rose the most in 10 years, reflecting a recovery from the effects of the pandemic and boosted by an increase in the number of working days from a year earlier.

The overall upbeat figures follow separate data released Friday that showed China’s manufacturing expansion cooled in April. The official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index fell to 51.1 from 51.9 in the previous month.

Global trade has kept up its pandemic-era winning streak, with Asian economies especially benefiting from the boom in goods orders, the Bloomberg Trade Tracker shows. Shipments from South Korea and Taiwan have surged, buoyed by demand for electronics

China, Thailand & Indonesia

Reinvigorating Japan's Industrial R&D

On our own dime

As one CEO of a large Asian company famously described Asia’s new attitude: “When you go in early, you’re not always right, but you have time to correct. If you’re a latecomer, you have to hit a hole in one. There isn’t any time for detours and mistakes; unless you get it right the first time, you’ll never catch up.”

Enough already, seems to be the collective sentiment in Asia. We have no time to wallow in fear about robots stealing jobs or AI humiliating our gray matter. We’re on the move.

And oh, BTW, we’ll do it on our own dime.

“For years,” argues McKinsey’s Future of Asia, “Western observers have talked about Asia’s massive future potential. But the future arrived even faster than expected. The question is no longer how quickly Asia will rise; it is how Asia will lead.”

Asia is spending big and spending fast for a technological advantage that can outrace a rapidly-ageing workforce; outrace the children of that workforce who want better jobs than their parents; and outrace the staggering needs of a burgeoning middle class that will number 500 million (China), plus another 500-600 million when combining the middle-class populations of the ASEAN with India and Indonesia.

And slowly, Asia is learning how to lead…again. It’s been a while in coming.

Any trade war is minuscule compared with providing for a middle class that the Brookings Institute forecasts will be the majority population in the world…for the very first time. With 88 percent of the next billion residing in Asia!

What’s at stake? An enormous middle class financially powerful, commanding $64 trillion (33 percent of the global economy). So powerful, in fact, that it could topple governments or create them in its own image, redistribute wealth, provide for the common welfare…or raise armies. Better treat them well!

Asia is well-acquainted with disruption

Disruption and rapid transformation are nothing new to Asians. They have been dealing with it since long before the Mongols arrived. War, revolution, famine, disease, mass migration, annexation, civil turmoil, humiliation, colonial oppression, just to name a few, have been their lot for centuries.

Why should a little automation throw them? It doesn’t. In fact, disruption from robot-driven automation for most Asians is the best disruption yet: it’s benevolent, it’s uplifting millions of lives; it’s going to make Asia’s economy a global best.

Although the epicenter of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is Asia, the rest of the world seems more upset about robots taking over the grunt work in Chinese factories than do the present and former human gruntees.

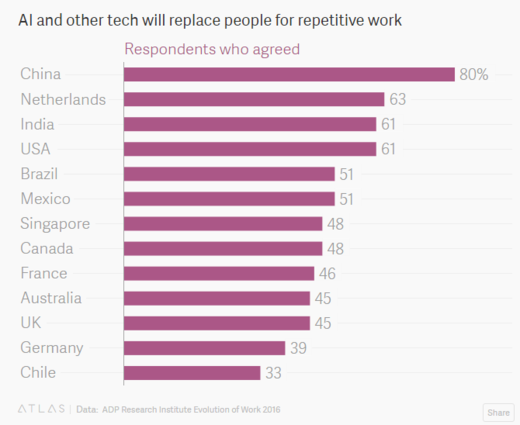

In ADP’s The Evolution of Work: The Changing Nature of the Global Workplace, eight out of ten Chinese respondents clearly see the inevitability of repetitive work being automated. They also want their children to aspire to more than line work in a factory.

Fully 80 percent of China’s citizenry feel that “AI and other tech” will substitute for them in the grunt work that they have toiled at for over thirty years.

Asians, especially the Chinese, don’t cringe at headlines like this:Production Soared After This Factory Replaced 90% of Its Employees With Robots.

With robot replacements, the above-referenced factory (Changying Precision Technology Company) in Dongguan City “experienced a 250% increase in productivity and an 80% drop in defects.”

China realizes that every factory will have to mirror this one in Dongguan City if the country is to have a chance at meeting middle-class demands.

Liu Qingtang, section chief of the Dongguan Economy and Information Technology Bureau, cites the 100,000 unfilled job vacancies in Dongguan as another motivating factor in turning to robots. Salaries, he says, are competitive with those in other developed countries, wiping out Dongguan’s historical edge in cheap labor.

Yang Wei, a young, former line worker and now a production supervisor at the factory, sees greater opportunity for advancement in managing robots to do his former job. He says that he now has time to learn more about the machines, to get better acquainted with the company’s products, and even learn to read engineering drawings.

Daring can be scary

Can the success at the Changying Precision Technology Company scale? Dongguan wants to see another one thousand factories automate in the same way, while China wants and needs many more Dongguans.

Yet, all of the change at Changying Precision Technology Company is but a first step, a beginning. When and how will Yang Wei know if his machines need repairs or the software an upgrade? How can he capture the data produced by the machines in order to sift it for clues on process improvement? How can he hook up notice of shipments of finished goods to backroom accounting systems? How can he resupply his machines with raw materials at the best price?

When will artificial intelligence (AI), predictive analytics, and an Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) fulfill the promise of the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

For Liu Qingtang, that’s how Dongguan can best serve the city’s nearly 10 million residents, as well as to help contribute to the well-being of China’s 10 other cities with 10 million or more residents as well as China’s 100 cities with one million or more.

That’s a lot of people? That was the purpose behind Changying Precision Technology Company going robot.

All those millions in all those cities with middle-class money and tastes. When each one of them thinks about buying a microwave oven, it tends to draw into sharp focus the notion of why factories need “a 250% increase in productivity and an 80% drop in defects.” And when all those microwaves switch on to re-heat a cup of tea, the draw on the country’s energy grids is staggering.

And what of the masses of layoffs from factories where robots now work? The Guardian reports that China’s center is moving west:

“Guiyang, for example, topped a few lists of the best-performing Chinese city last year, as the once-sleepy capital of the country’s poorest province saw a boom in cloud computer servers and telecommunications, with e-commerce giant Alibaba a major investor.

“Factories are moving inland from the coastal regions in droves. Xiangyang and Hengyang, both now home to more than 1 million people, are swelling as low-end manufacturing moves to cities with cheaper labor.

“The local government in Zhengzhou, for its part, transformed a dusty patch of land in central China into an industrial park overnight; Foxconn, the world’s largest contract electronic manufacturer, now makes about half of all iPhones there and has also built a plant in Hengyang.”

Pioneering change at the epicenter of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is far from perfect, but it’s happening, moving quickly, and it’s well-intentioned.

There are lessons here.