Consumption as China’s Cure-All: Robots, People & Lots of Money

What would gigawatts of consumer spending look like? Think, Singles’ Day every day! …Think also, who cares about exports?

Plus, lots of income is unreported, so this is really the lower boundary for true household income.” —The One Hour China Consumer Book

Consumer power on display

Once each year China gives the world an inkling as to the eye-popping power of its consumers on a spending binge. It’s called Singles’ Day. In 2019, the one-day phenom posted $38 billion in sales (25% over last year’s $30.8 billion all-time record).

As a Quartz headline exclaimed: “For all the hubbub about the US-China trade war, trade is a fraction of China’s economy.” And  Singles’ Day drives home the notion that China’s real economy is right there at home.

Singles’ Day drives home the notion that China’s real economy is right there at home.

Amazingly, there’s still a ton of growth ahead for Singles’ Day. Although the penetration rate on the east coast is 85 percent, out west in the hinterlands penetration is barely 40 percent.

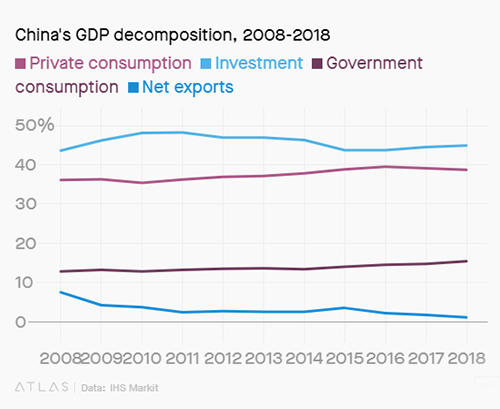

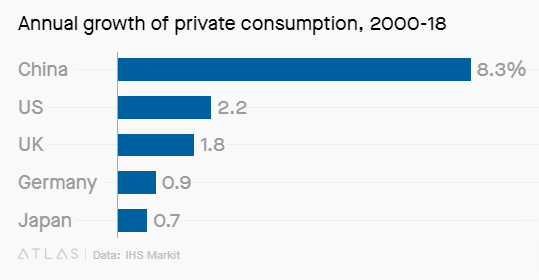

Singles’ Day also highlights a growing trend in China: “China’s economy is much less reliant on exports. Indeed, its current account surplus is quite small at ~1 percent of GDP and this is in large part a result of increased local private consumption, which now accounts for 40 percent of its GDP.”

It took only 16.5 hours of 2019 buying to top 2018’s total. Amazingly, $13 billion rang up during the first hour! Singles’ Day is billions bigger than Black Friday and Cyber Monday combined.

If you were unfortunate enough to be a delivery driver on November 11th, the staggering total of brown boxes bound for customers was 535 million. On the fortunate side of things, if you needed a job, all those hundreds of thousands of drivers, plus the millions of order pickers and package handlers feeding deliveries, all represent a burgeoning trend in service jobs.

Singles’ Day is much more than garish tote boards ringing up sales, Jack Ma waving to ecstatic crowds, and Taylor Swift being Taylor Swift to a Chinese audience.

Remove robots and automation from this otherwise rosy future, and it would all collapse.

Rising consumer spending, and the strategic use of robots and automation technologies are a great natural teaming that will power China’s next great surge.

Singles’ Day is an annual temperature taking to see how well everything’s coming along.

Robots + consumption = happy China

If Xi Jinping can keep his country’s economic recovery together long enough for China’s consumption to return to 50 percent of GDP—where it hasn’t been since 1985—he’ll have unleashed a financial juggernaut of historic proportions.

Hovering at 40 percent of GDP in 2018, consumption is coming back, and quickly! In comparison, Japan’s consumption rate is 61 percent of GDP, while the U.S. percentage is 68.

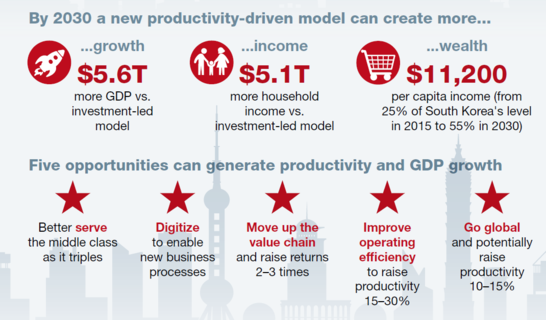

A McKinsey Global Institute report sees a potential $5.6 trillion in additional GDP by 2030 and a potential household income gain of $5.1 trillion coming from a new “productivity-led economy”. Like the kind of productivity portrayed in the game plans from China’s 13th Five-Year Plan and Made in China 2025: big canvas, country-wide transformations.

The rewards are non-trivial

As Jeffrey Towson and Jonathan Woetzel argue in their The One Hour China Consumer Book: “just getting consumer spending back to 43 percent of GDP, the level in 1995, would have a huge impact…It would also create the largest consumer market in the world.”

To get a feel for what that might look like, think Singles’ Day every day ($38 billion in sales in 2019).

And it could happen much sooner than later because gigawatts of consumer spending, springing from the wallets and purses of a rapidly escalating middle class, are hurtling toward China…and hurtling as well into the southeast at the 630 million consumers in the 10-nation ASEAN Economic Community.

The gigawatt crowd

China alone has an existing middle class of 430 million people, which is expected to ramp up to 780 million by 2050. The ASEAN’s 150 million class will balloon to 400 million before 2050.

Between China and the ASEAN that’s an additional billion-plus, middle-class consumers by mid-century, which is like adding a population the size of Chile every year for the next three decades. In fact, 2018 saw China add a city the size of Istanbul to its ranks as it welcomed 15.5 million newborns, (far fewer than the record-setting 18.5 million in 2016).

In toto, by 2050, China and the ASEAN are looking at a middle-class consumer behemoth nearly equal to the populations of the U.S. and Europe combined. And that’s just the middle class!

Big time consumption is the kind of job that only a middle class can pull off because it alone has the size, financial wattage, and influence. Consumption from the upper class is too little to drive it and the purchasing power from the lower class is too feeble to buy most anything that market economies need to succeed in a big way.

That same middle-class ambition spins out side benefits as well. The Kauffman Foundation conducted a study on the demographics of entrepreneurs and found that only 1 percent come from extremely poor or extremely rich backgrounds, which leaves 99 percent coming from the middle class.

The brisk pace of entrepreneurial dynamics so evident across China and Southeast Asia these days may well be a byproduct of this roiling middle class.

Bottom line with consumption coming from a population group of that size—with all of its typical middle-class needs, wants and demands—is that no manual-labor industry, no matter how large or well organized, could ever hope to satisfy. Even the basics of decent food, clean water and adequate shelter will be impossible to provide. Without robots and robot-driven automation, it’s a looming formula for catastrophe.

McKinsey’s call to “improve operating efficiency (see chart above) to raise productivity by 15-30 percent” is necessary to meet the demands of China’s burgeoning consumer growth, but it will also inure to the benefit of the ASEAN.

Such benefits to the ASEAN might take the form of transferring some of China’s manual manufacturing jobs south where wages are lower and automation is slower in arriving. The textiles, clothing and footwear industry (TCF) is one possibility. “TCF is monopolized by China, which has a dominant market leadership: it accounts for over 31 percent of global textile exports, 37 percent of clothing exports and over 39 percent of footwear exports.”

Some or a large part of TCF resettled in the ASEAN would provide a substantial positive jolt to countries across Southeast Asia; and make lasting friendships for China as well.

Like its East Asian neighbors, Korea and Japan, China is greying. The ASEAN is not. Median age in the ASEAN is 27 while that of China is 32. There’s potential for magic in that difference for both China and the ASEAN.

China’s aging, shrinking workforce will help to push manual labor south as China automates. “At the moment, one in seven of the population [China] is over 60. By 2050, the share will rise to more than one-third.” China’s rock ‘em sock ‘em middle class of 500 million will have 166 million people over 60. And that’s just the middle class.

With women of child-bearing age (15-49 years) due to fall by about 5 million each year over the next four years, prospects for a sustained baby boom seem remote.

Chinese factory workers are in decline, while robots and automation in factories are quickly replacing them. The country has been the world’s largest market for industrial robots since 2013 (68,000 in 2015) and it will only get larger, according to the International Federation of Robots, which estimates China will account for 40 percent of the global industrial robot market by 2019.

The nearby ASEAN is a perfect place for China to park but still control such retro-industries. The ASEAN, in turn, automating much more slowly than its massive neighbor to the north, has years yet to go before facing the same automation imperative.

Tony Fernandes, AirAsia Group’s CEO, is a believer in the rise of China’s middle class opening up strong opportunities for the ASEAN. His Malaysia-based air carrier flies to 19 Chinese cities, taking part in the $215 billion (a record!) that Chinese travelers spent last year to destinations outside of China.

At the World Economic Forum’s ASEAN summer meeting in June, Fernandes encouraged ASEAN members to shift from supplying China with just commodities to creating and selling ASEAN brands to China’s middle class. AirAsia did, and it worked.

AirAsia’s success, in turn, allowed him to buy a thousand engines from GE, which are now serviced from a GE service facility in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. That change from supplier of commodities to purveyor of brands, he said, is important difference maker for all the 10-member AEC countries to pursue.

The consumption cure-all

“The number you really want to keep in mind is household income,” say Towson and Woetzel. “You can’t have consumption without income. And here’s where it gets really awesome. China’s household income is huge. It is now likely above $5 trillion a year. Plus, lots of income is unreported, so this is really the lower boundary for true household income.”

So, if we add China’s household income of $5 trillion-plus a year, according to Towson and Woetzel, together with the McKinsey post-automation estimate of an additional $5.1 trillion for households, that’s give or take some $10 trillion in the hands of China’s citizens.

The International Monetary Fund calculated China’s total 2018 GDP at $13.06 trillion.

If China’s consumers were a country, a $13 trillion GDP would put it way up near the top. Looks like consumer purchasing power could get very interesting in China very soon.