Protopia and the End of Humans Coding Anything

With “developer dropout” shockingly 30%—and rising! are humans ill-suited as programmers? Would AI/ML be a better choice?

Waystations

Humans as programmers might just be a temporary waystation along the journey to something with a higher calling for our vaunted brains to handle without burnout or obsolescence.

Nnamdi Iregbulem is out with a curious article, Why We Will Never Have Enough Software Developers, in which he says: “Software development has a serious retention problem. Developers are dropping out of the profession in large numbers despite efforts to grow the number of computer science graduates and software engineers.”

Then he drops in a very telling stat: “At age 26, 59 percent of engineering and computer science grads work in occupations related to their field of study. By age 50, only 41 percent work in the same domain, meaning a full ~30 percent drop out of the field by mid-career. Developer dropout is real. Here’s why.”

The entirety of his article is here reproduced below. It’s a thought-provoking piece, and a bit scary. After considering his reasoning plus a few more of his stats, the scariness leaves and is replaced with a dawning realization that programming really sucks; there must be a better way to program and still retain a halfway descent shot at a balance of good work life and a good career arc for a better future.

Iregbulem furthers: “Programming-related jobs have high rates of skill turnover. Over time, the types of skills required by companies hiring software developers change more rapidly than any other profession.

“About a third of the change in required skills in computer-related occupations is due to specific new software.” For example, important-to-know software from 2007 was unimportant-to-know software and obsolete by 2019.

“Suffice to say,” he writes, “software development is a rapidly changing profession. You might think, however, that skill change would eventually settle down as one becomes more experienced. You’d be wrong. The skills for software engineering jobs change rapidly throughout the entire career lifecycle.”

Kevin Kelly in his book The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, ascribes such rapid software obsolescence to living in a protopia: a state of becoming rather than a destination. He claims that technology is taking us to protopia, a place that never arrives, that keeps moving forward as its natural state.

Software changes constantly. Kelly says that the average lifespan of an app is but 3 months. Not much of importance in the digital world can compete with that kind of brevity.

Maybe programming is just such a transient place for humans to reside. Maybe it’s better if software does all the coding, like Google’s AutoML system recently “produced a series of machine-learning codes with higher rates of efficiency than those made by the researchers themselves. In this latest blow to human superiority the robot student has become the self-replicating master.”

“AutoML was developed as a solution to the lack of top-notch talent in AI programming. There aren’t enough cutting-edge developers to keep up with demand, so the team came up with a machine learning software that can create self-learning code.

“The system runs thousands of simulations to determine which areas of the code can be improved, makes the changes, and continues the process ad infinitum, or until its goal is reached.”

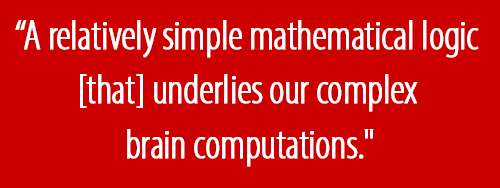

Sooner than we think, we may be laughing at ourselves at the folly of humans coding software, when we emerge from travelling through this Algorithm Age having been totally unaware that our brains were meant for higher order work. Maybe that place is where Dr. Joe Z. Tsien, neuroscientist at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, says our brains will tussle with a single, grand basic algorithm, “the fundamental principle for how our billions of neurons assemble and align not just to acquire knowledge, but to generalize and draw conclusions from it…A relatively simple mathematical logic [that] underlies our complex brain computations.”

Maybe that place is where Dr. Joe Z. Tsien, neuroscientist at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, says our brains will tussle with a single, grand basic algorithm, “the fundamental principle for how our billions of neurons assemble and align not just to acquire knowledge, but to generalize and draw conclusions from it…A relatively simple mathematical logic [that] underlies our complex brain computations.”

Or, maybe there’s an emerging link between the human mind and quantum physics that becomes our higher order work.

In the meantime, Iregbulem’s argument resonates with a fascinating look at the brain-wearying world where no human has too long a stay.

Why We Will Never Have Enough Software Developers

by Nnamdi Iregbulem

We will never have enough software developers.

Developers are dropping out of the profession in large numbers despite efforts to grow the number of computer science graduates and software engineers.

Here’s why.

Software development has a serious retention problem: Developer dropout is real:

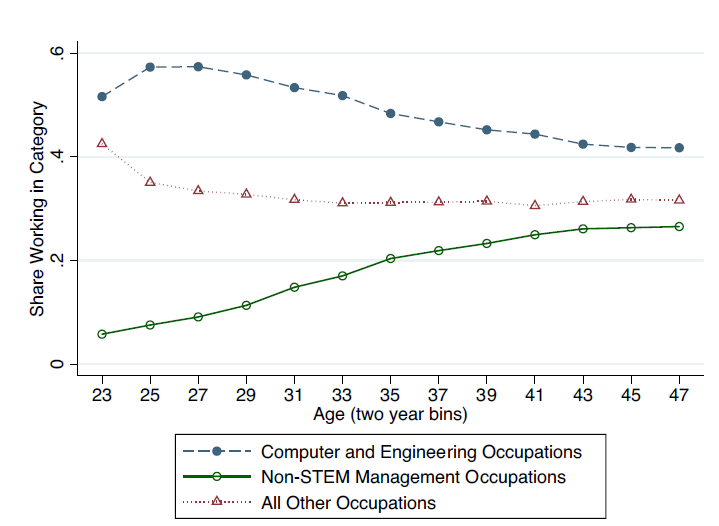

At age 26, 59% of engineering and computer science grads work in occupations related to their field of study. By age 50, only 41% work in the same domain, meaning a full ~30% drop out of the field by mid-career

In contrast, engineering and computer science majors who join unrelated fields upon graduation retain at much higher rates, with only 10-15% switching out after the age of 26.

Engineers often leave engineering for non-STEM management roles. Graduation into management is not surprising. What’s surprising is that these are non-STEM positions. Engineers swap technical roles for non-technical roles over time.

This phenomenon, which I’ll call “developer dropout,” is a real problem. What’s behind it?

Out with the old skills, in with the new skills

Programming-related jobs have high rates of skill turnover. Over time, the types of skills required by companies hiring software developers change more rapidly than any other profession.

To demonstrate this, researchers analyzed job postings on more than 40,000 online job boards and company websites between 2007 and 2019, controlling for employer, location, and occupation. They defined “new” skills as those that were rare or non-existent in 2007 but prevalent in 2019 and “old” skills as those that were prevalent in 2007 but rare or extinct in 2019.

While only 30% of all job vacancies required at least one new skill by 2019, 47% of computer and mathematical jobs required at least one new skill (i.e. a skill that was not common back in 2007)

This compares to less than 20% of jobs in fields like education, law, and community and social services

In addition, 16% of jobs in computer and mathematical fields in 2007 required a skill that was obsolete by 2019 (i.e. a skill that was common in 2007 but relatively rare in 2019), more than double any other job category.

About a third of the change in required skills in computer-related occupations is due to specific new software:

The fastest-growing software skills between 2007 and 2019 include Python, R, and Apache Hadoop.

Software that was popular in 2007 but effectively obsolete by 2019 includes QuarkXpress, ActionScript, Solaris, IBM Websphere, and Adobe Flash (ah, finally a name I recognize)

Data science, machine learning, and AI saw big increases among technology-intensive jobs as well. For example, the number of STEM-related jobs requiring skills in machine learning and AI grew more than 4x from 2007-2017, touching more than 15% of STEM jobs.

To better compare rates of skill change across occupations, the researchers came up with a measure of skill change that tracks the absolute growth or decline of various skills within each profession from 2007 to 2019. Occupations whose required skills change rapidly in prevalence among job postings receive a high score, while jobs whose skills do not change much receive a lower score.

Computer-related occupations receive the highest score by far, 4.8. Note that the mean and standard deviation of this measure are ~3 and ~1 respectively, so computer-related jobs are nearly two standard deviations away from the typical job in America

Meanwhile, jobs in education and those involving manual labor have very low skill change scores, typically less than 2.

We can get even more granular and look at specific job roles. This level of detail makes the difference even more stark (only showing the fastest changing roles).