ASEAN Profiles

Singapore: Seeking a Bridge Between

Can robotics become a key contributor in shift from simply “adding value” to “creating value”?

“Singapore has the basic assets for industrialization.

Her greatest asset is the high aptitude of her people

to work in manufacturing industries.”

—Albert Winsemius, Singapore, 1961

Staying great is never easy

Although Singapore’s robotics research community is world class and its laboratories consistently output ingenious robotics and allied high-tech complements to robotics, the pace of technology transfer from lab to the commercial marketplace is far from strong.

To leverage robotics as a revenue generator on the global stage and to position Singapore as a core developer of robotics technology, much more will need to be done…and done quickly.

The good news is that there’s a worldwide robotics revolution going on, especially in Asia.

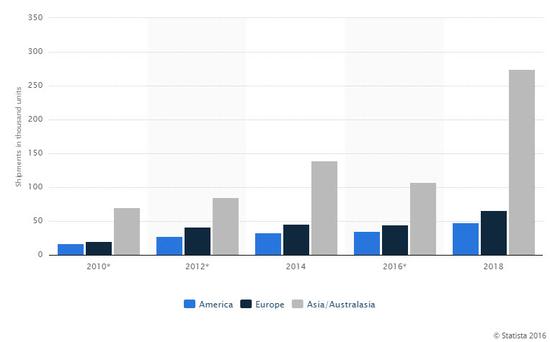

Shipments of Industrial Robots Through 2018

With global sales of industrial robots hitting $10.7 billion in 2014, reports theInternational Federation of Robotics (IFR); and with the Boston Consulting Group projecting sales to skyrocket to $67 billion by 2025—Asia being by far the largest buyer—Singapore has an unprecedented opportunity to supply robotics technology into this nine-year window, if it has the machines, parts and expertise to export into Asia.

To do so would mean new manufacturing jobs designing and building robots, a huge new revenue source for the country, as well as the global prestige that comes with being a provider of essential industrial technology.

Can and will Singapore get in on this multi-billion dollar boom?

Maybe.

All the elements for success are resident in abundance, but there seems to be a lack of decision making as to which robotics technology to prioritize and how to accelerate those prioritized technologies into products and then into marketplace successes.

Part of that potential success already exists in the startup community where some very significant robotics engineering is taking place. That nascent force needs to be recognized and thoroughly nurtured as well.

The clock is ticking, and Singapore is too small and too vulnerable to afford to make many mistakes or missteps.

A master plan is needed that is simple, straightforward and results oriented. Singapore is renowned for putting such plans together and making them work; one such simple plan is the famous 5-point plan from the 1960s that made Singapore what it is today.

Making robotics work for Singapore has a lot to do with getting back to the basics that made it great.

A backstory of vigilance

Slightly larger than Chicago (278 sq. mi.) with over twice the population (5.5 million), the city state Republic of Singapore has always had to live on the sharp edge of economic uncertainty.

It has no agriculture to speak of beyond supplying a few vegetables and eggs to the city; manufacturing accounts for 5 percent of GDP and employs slightly over 400k people. It imports roughly 90 percent of its food.

Walk 26 miles one way or 14 miles in the opposite direction and that’s it for Singapore’s land mass; and while walking in any direction one would pass over 18 thousand people crammed into every square mile.

Even its water supply is precarious. Water comes from what Singapore calls the Four National Taps: catchment water from rain and storms, desalinated seawater, imports from Johor, Malaysia, and NEWater, which is treated wastewater.

Such a place can make life expensive, and it is. Gasoline at the pump is over $6 per gallon; a 100oz box of laundry detergent is $8; a pair of Nike running shoes is $93; and beer at a local bar is $8. Expenses like that look mighty steep where the average factory worker makes $4900 per month or $1200 per week, which for most any other place in the world would be nice pay to take home to the family.

On the flip side, Forbes commends the city-state’s economic status: “unemployment is very low (2 percent). It has no debt. The economy (GDP $300B) depends heavily on exports, particularly of consumer electronics, information technology products, medical and optical devices, and pharmaceuticals.” Its container shipping business is one of the largest in the world, and its financial sector is in the top five on the planet.

Ngiam Tong Dow, who served in the Singapore Administrative Service for more than 40 years and was former chair of the Economic Development Board, remembers well the grim old days of 1960:

“At the time Singapore’s economy was stagnant and its infrastructure crumbling. It was a city of 3 million people, with over 14 percent unemployed and many living in overcrowded and dangerous housing. Under these circumstances, it was imperative to create jobs fast and then build homes for the people.”

Singapore climbed out of those dark times in large measure to an ingeniously crafted 5-point recovery plan formulated by Dutch businessman and UN advisor to Singapore, Albert Winsemius, and superbly and consistently implemented by the first Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kwan Yew, and his young government.

Winsemius recalled later that world opinion was: “Singapore is going down the drain; it is a poor little market in a dark corner of Asia.”

His 5-point plan, which he personally tabbed as “Expectations and Reality” revolved around core basics: factory jobs; housing; key anchor investments from Philips, Esso and Shell; build a financial hub; and build a container traffic hub.

Four decades later, voila, modern Singapore.

Almost six decades later, it now has problems, the end result of which no one wants to see become a repeat of Mr. Dow’s 1960.

Singapore went from a Third World country to a First World country in forty years, but today, with nearly two decades of comfortable living behind it, the economy is in sharp decline.

The island needs to help itself…fast!

According to Channel NewsAsia: “For the full year [2015], manufacturing fell by 5.2 percent, the first annual decline since 2009, when industrial output fell by 4.2 percent. It is also the steepest decline since 2001.”

Ng Weiwen, economist for ANZ Research, said “The steep and continued contraction in the manufacturing sector underscores our view of the ongoing trade recession.”

From the government’s side, it’s paying close attention to the uncertain economic situation, with official estimates predicting growth in 2016 to range from 1 to 3 percent. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said that the government does not expect a downturn as severe as the 2008 global financial crisis.

But a downturn nonetheless. Words like downturn, recession, and decline are not healthy for a teeny country that has basically lived by its wits and hard work since its early days in the 1960s.

Minister for Trade and Industry S. Iswaran reasons that Singapore must “shift from simply adding value to creating value” in order to build a future of economic potential. Iswaran also serves as the chair of the CFEs subcommittee for Future Growth Industries and Markets, a perfect vantage point from which to scout the horizon for technology that could generate potentially new revenue streams.

Enter robotics

Robotics presents a perfect scenario for “value creation”.

Such a robotics-centric scenario does not, however, include the integration of robots from manufacturers from Japan, Germany or Denmark into large-scale or SME manufacturing and logistics. As helpful as such deployments can be, they are being implemented in Singapore to increase automation to improve productivity and, as such, are really adding value and not creating it.

Value creation in robotics would entail the island nation developing and building its own robots as end products that could then be exported worldwide, especially to East Asia and other members of the ASEAN Economic Community.

Competing with established manufacturers like ABB, KUKA, Fanuc, Yaskawa, etc.—the big boys of robotics—would seem to be too far a reach; even a relative newcomer like Universal Robots and its revolutionary collaborative robot is, at this stage, way out of Singapore’s league.

Singapore needs to survey the automation landscape for niche robotics industries that it can enter and have a reasonable to a very good chance of winning, even better if those niches presented themselves as very much needed in Asia.

Three such robotics niches are very much evident in Asia and are glaringly under represented or not represented at all:

1. Autonomous mobile robots for manufacturing and logistics for which Singapore already has a nascent indigenous industry that is building remarkable machines. Particularly warehouse robots, which are virtually nowhere in evidence in Asia, except for the newcomer from India, Grey Orange(just opened an office in Singapore).

Market forecast: WinterGreen Research projects the logistics robot market to grow to $31 billion by 2020.

2. 3D printing for both mass production and Cloud manufacturing as well as the 3D printing of specialty parts for both healthcare and aviation. The ease of entry into 3D printing is remarkably low, especially so now that most of the key patents have expired.

Everything from mass produced electronics components to prosthetic limbs are possible with 3D production tools.

Market forecast: 3D printing market ranges from: $7 billion by 2020, on 18 percent CAGR (Paul Coster of JP Morgan), to bull market scenarios as high as $21.3 billion by 2020, on 34 percent CAGR (Ben Uglow of Morgan Stanley).

3. Robot part manufacturing 90 percent of which is currently controlled by Japan. Parts such as actuators, vision and other sensor systems, batteries and power systems, and advanced materials for robots present as superior opportunities. Singapore, with a world-class parts manufacturing industry already in place for consumer electronics, information technology products, medical and optical devices, and pharmaceuticals, is ideally suited to compete for the robot parts business. And, for that matter, creating systems and parts for the burgeoning technology surrounding driverless cars, trucks and busses.

Market forecast: The market for robot parts, robot software, and related safety materials now approaches $22 billion. Forecast at a five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.9% between to 2018, when it’s expected to surpass $29 billion.

Asia as a segment is expected to increase and reach $10.6 billion in 2018, a CAGR of 6.3%.

Addenda with potential

The above three niche areas are exactly what the Ministry of Trade and Industry reiterated in its addenda to President Tony Tan Keng Yam’s opening address at Parliament: “Singapore can develop growth clusters in niche segments, particularly leveraging on the Republic’s technological and geographical strengths.” From those addenda:

Number one:“Advanced Manufacturing: Existing capabilities will be enhanced to expand into new types of high-value manufacturing. Investments in technology like 3D printing and robotics will help grow competitive niche segments.”

Number three: “Logistics and Aerospace: Deepening specialized logistics capabilities will help keep Singapore well-connected.”

Seeking a bridge between

Robotics technologies are well known, highly advanced and well worked in Singapore’s universities, but how much of it is ready for the process of technology transfer to commercialization in the near term? Sadly, not much.

Patent filings are always a good indicator of who is generating key technologies for the world’s marketplaces. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) of the top 20 countries driving patent filings in 3D printing, nanotechnology and robotics: Singapore is 18th in patents for 3D printing; 11th in patents for nanotechnology; and absent from the list in robotics.

Clearly, if Messrs. Winsemius and Yew were today putting together a 5-point recovery plan for Singapore’s future in technology, those WIPO rankings would be unacceptable, especially for a tiny country living by its wits and work ethic.

As Singapore’s long-time Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee used to say: “Unless you have economic growth, you die.”

Looking hard into the robotics programs in Singapore’s university research systems gives little evidence of Swee’s “economic growth” bursting out anytime soon.

Yes, there is superb robotics technology afoot everywhere on the island, but very little is ready to produce revenue and create jobs.

A close look at these formidable institutions does not turn up much:

1. Singapore Polytech

ADVANCED ROBOTICS & INTELLIGENT CONTROL (ARICC)

2. School of Electrical & Electronic Engineering

CENTRE FOR ROBOTICS AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

2. National University of Singapore

Advanced Robotics Centre

3. Nanyang Technological Institute

Robotics Research Centre

4. Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology

5. Nanyang Polytechnic

Robotics & Automation Centre

6. Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology

7. Singapore Institute for Neurotechnology

Centre for Life Sciences, National University of Singapore

Robotics & Rehabilitation

What seems to be needed here is a plan to prioritize research and to create a blueprint to quickly execute that work in order to produce viable robotics products and new companies that Singapore can nurture into a strong and resilient robotics industry.

There is a huge upside for robotics to thrive in Singapore as a bustling industry with global impact, but it may take some hard decisions and some getting back to basics to successfully pull it off.

A plan, not unlike that of the Winsemius/Yew 5-point recovery plan, would seem to be in order; a plan that could act like a bridge between the development and deployment of a fledgling robotics business maturing into full-fledged successes.

A microcosm of potential…and the future

Solutions to Singapore’s need for robotics technology are nearby.

Not far from the Jurong River on Penjuru Close in Singapore’s Jurong Industrial Park sits an unremarkable three-story factory building within which some very remarkable engineering is taking place.

Founded in 2006, and now profitable to the tune of $8 to $10 million annually, this “playground for tinkerers and geeks” numbering about fifty staff are building out chunks of the country’s robot future.

Meet Hope Technik, a “playground” that encompasses 50,000 square feet that is broken out into engineering cells for what seems like dozens of company projects. Tech in Asia dubs the place “one of the most underrated tech companies in Singapore.”

“We created the company because we like to design and engineer things,” Michael Leong, co-founder (together with Peter Ho) and general manager of Hope Technik, told Tech in Asia. “We started offering services to help clients design and engineer products and solve problems. We wanted to be the best engineers in town.”

One such project should perk up the ears of Minister for Trade and Industry Iswaran and his call for “value creation”. Hope Technik has built an autonomous mobile robot for manufacturing and logistics called the SESTO AGV and plans for another called the APT UGV (2016).

The SESTO AGV is market ready, and merely needs a boatload of salesmen to pitch it from one end of Asia to the other. Ramping up to build the SESTO AGV in quantity may be a challenge, but that means jobs and exports, which should be a no brainer.

Remember there’s a logistics robot market out there forecast to grow to $31 billion by 2020; it’s waiting with lots of potential sales for companies like Hope Technik —and hopefully others from Singapore!— to come along.

Hope Technik is the kind of technical leader with promise that would have brought a broad grin to Albert Winsemius.

Where there is one such company, Singapore surely has others. If not, it should make more of them, and soon

Let the search begin. There’s an industry waiting to be built.

Hope Technik, Singapore