How Technology, Even Low-Tech, Takes Jobs

Lessons learned about automation from the low-tech shipping container

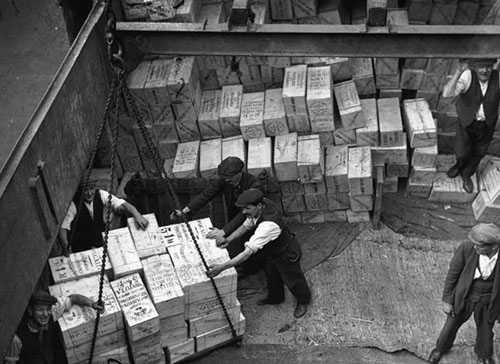

According to the New York Times, there were 35,000 longshoremen working the docks in New York City in 1960; today there are fewer than 3,500. After the shipping container revolution of the 1950s, the number of dockworkers required declined by over 90 percent.

Productivity per hour vs. consistent productivity

The sprawling Los Angeles-Long Beach port complex will reach capacity by 2022 “with the current mode of operation.” Automation, in the form of autonomous vehicles is being introduced to mitigate the 2022 deadline, but it’s meeting with opposition from labor unions.

Curiously, the records of “automated terminals in the US and Europe indicate that automation does not increase total terminal productivity per hour… the automated terminal produces consistent productivity “like a machine” 24 hours a day.” Machines have a knack for “consistent productivity”.

But will it make my laptop cheaper to acquire?

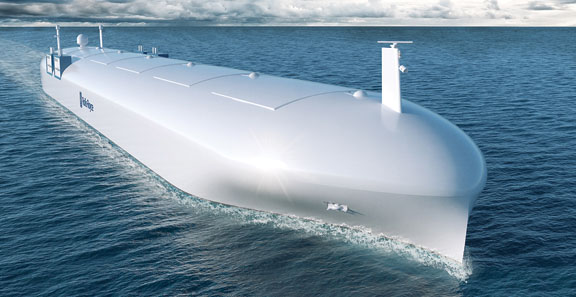

Slow boat from China

My HP laptop, which is assembled in a factory in Chongqing, China, costs an extra $2.00 to travel by container ship to my desk. Not bad. Small extra cost on my part to pay out for such a good deal. But that’s only if it comes by container. If it leaves China any other way than by container ship, then it suddenly becomes prohibitively expensive to buy. Hence, I can’t afford an HP laptop assembled in Chongping.

So, I guess that I need to thank Malcolm McLean, inventor of the shipping container and the container ship, for making it possible for me to own an HP laptop.

However, if I’m a longshoreman standing in an unemployment line, I could probably point to the shipping container and the container ship as the reason for my joblessness.

According to the New York Times, there were 35,000 longshoremen working the docks in New York City in 1960; today there are fewer than 3,500. Worldwide, the ranks of dock working jobs has been gutted, and will never return.

On April 26, 1956, McLean put 58 containers, aboard a refitted tanker ship, the SS Ideal X, and sailed it from Newark, NJ to Houston, TX.

Around my apartment there are hundreds of other items (probably 99 percent from China) that took the same journey to my home, which all or most might be prohibitively expensive to buy if they were non-containerized and came via a slow boat from China.

In pre-container days, stuff cost $420 per ton to ship; containers have shrunk that expenditure to $50 per ton. In the process, world trade has gone from 20 percent of global GDP to around 50 percent.

“Despite rising volumes of cargo, since early 1960’s every major US port experienced unprecedented decline in employment.”

In short, we are getting more for less, and the low-tech container is the reason.

Will we ever go back to the way goods were shipped in 1960? Consumers want the goods and like paying less for them. A dynamic that won’t change any time soon. Any kind of automation, low tech or high tech, that enhances productivity and lowers prices will always win out, including autonomous docks like the Los Angeles-Long Beach port complex.

“Consistent productivity”? We’ll take it.

Fear and loathing of robots

The headline spat out in an Associated Press (AP) release read: Mexico taking US factory jobs? Blame robots instead. Within minutes after the headline appeared, thousands of media outlets from small guys like Townhall.com to big guys like Fox Business reacted by pushing out another robot job-threat story to millions of ears and eyeballs around the world.

A TV feeding frenzy on job-stealing robots ensued for two days thereafter.

Robots, the handy media punching bags for any economic job woes, are getting another battering. Grim and menacing “If it bleeds, it leads” headlines quickly engage readers and sell advertising. Lately, stories about machines that steal livelihoods are bleeding bigtime attention!

But are the headlines true? Will this perceived robot threat continue to grow and make itself the menace of daily life for millions worldwide? Plus, isn’t everyone more than slightly nauseous listening to robot apologists cite the “three Ds” of robots culling only the dull, dirty and dangerous jobs? Ugh!

Bottom line: It’s not about robots. It’s all about technology. Technology has been unkind to masses of jobs since Rocket, Stephenson’s locomotive of 1829. Robots are technology’s newest Rocket.

Where formerly twenty dockworkers could load twenty tons of cargo per hour, it now took one port crane and one operator one hour to load 400 to 500 tons of containers.

What came of all those tens of thousands of hard-working fingers that yanked the seeds out of cotton before Eli Whitney came along?

We can blame it all on technology, if we dare; yet technology is the best and ablest force we have to push reluctant humanity into bettering lives, extending lives, and creating millions of previously unimagined new jobs, seemingly out of thin air.

Jobs that will, over time, also become obsolete as technology repeats itself—as is its nature—all the while hurtling us forward to some as yet unknown destination.

“Endless newbies” is what Kevin Kelly calls us in his book, The Inevitable. “Because the cycle of obsolescence is accelerating,” he writes, dangling the fact that the average lifespan of a phone app is a mere thirty days, “you won’t have time to master anything before it is displaced, so you will remain in the newbie mode forever.”

Neanderthals did the exact same jobs as their forebearers: unwaveringly repeating everything for 400,000 years. What did it get them? Extinction!

Multi-billions of dollars were quickly invested to create a global network of container ports and container ships. Where would places like Singapore be today without the humble, low-tech shipping container?

The shipping container enabled Just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing, which enabled SONY widescreen TVs to get on living room walls a heck of a lot faster.

And wouldn’t you know it, multiple thousands of new jobs and careers tumbled out of the process; jobs that never were, but suddenly were.

The Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) has mapped these new jobs. Of course, Kelly’s cycle of “accelerating obsolescence” is hard at work on them, but that’s for us to deal with.

New robot fear factor

The next iteration of robot fear soon to be appearing regularly in headlines will be humanity’s fear of “smart” robots. Today’s robots are poor dumb critters compared to the AI-driven robot generations just around the corner.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in robots will send out shock waves. We’ll no longer fear the robots that just work tirelessly all day and night, and then go off to plug themselves in for recharging; rather, we’ll fear the robots that think about what job to do next, how to do it and why, even if they’ve never previously attempted the job.

But why the fear?

Hasn’t social media already shown the way to dealing with these perceived or real threats? “Collective influence” is what Kelly calls it: the sum outperforming the parts.

We need to deal with the rise of robots, and to do it together, collectively, and not be emotionally ripsawed by every scary headline. We need to do something now, and not pull a Neanderthal, endlessly repeating the old while the new makes us extinct.

All of us “endless newbies” collectively acting in concert to get us into a position to succeed with our robot friends is a good beginning. Then we need to stand up the technology that will produce the as yet unimagined jobs of the future.

That’s a tall but exciting order to fill.

To borrow from Abraham Maslow, we need to be “self-actualizing”, but as a community, not just as individuals.

And lo, even the humble shipping container has now acquired smarts:containers can listen and speak!