The Gripper Chronicles

Grippers Chasing Cobots to Fame & Fortune

With cobot marketplace forecast at $9.2B by 2025, every cobot will demand a “skillful” gripper

As 2020 approaches

It was evident at AUTOMATICA 2018 that cobots had taken over the show, and evident as well that gripper manufacturers were crashing the party with myriad new tech and new capabilities to complement every cobot need.

See: AUTOMATICA 2018: Cobots and Grippers Rule!

Now wrap your mind around:

AUTOMATICA 2020

“New Ideas for the Automation of Tomorrow” Cobots & Grippers will again dominate the action for 2020.

The forecast looks awesome!

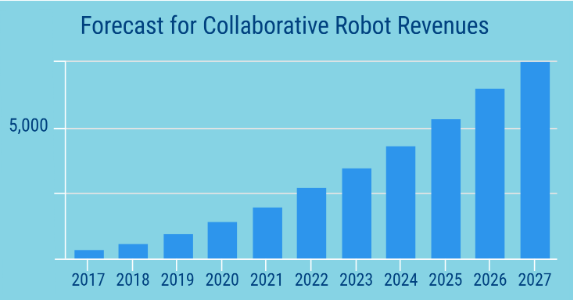

Although research puts cobot sales under a billion dollars (2017; projected by IDC to hit $1.3 billion in 2019) and gripper revenue slightly higher at $1.5 billion (2017), the upside for both is off the charts. Cobots are forecast at $7.5 billion and to account for 29 percent of the industrial robot market by 2027. Loup Ventures is more generous, predicting “by 2025 we believe the industry will ship over 434k cobots per year and equate to a ~$9.2B market. This growth implies a 56.5 percent CAGR.”

See: Every Factory’s New Best Friend…the Cobot

Asia-Pacific is expected to grow at the highest CAGR with China dominating the market in this region.

The chart below, Forecast for Collaborative Robot Revenues, shows the acceleration getting ready 2019 into 2020; thereafter, it’s a rocket ride for seven straight years.

Every cobot needs a gripper

AUTOMATICA also showed that cobots have a strong preference for grippers that are electric, adaptable, and smart, with a big emphasis on smart. BIS Research claims that 15,000 “AI cobots” will be sold annually by 2021, creating a market of $2 billion.

As for cobot safety, like a car with a new set of brakes, safety will be a given. Cobots with dubious stopping power will be DOA; insurers won’t touch them.

As 2019 unfolds, gripper manufacturers number some two dozen; and are showing gripper offerings that are electric, wildly diverse, well-engineered, and almost all are tending toward some degree of intelligence.

In addition to established gripper manufacturers, there are newbies with bright ideas and financial backing that have recently jumped into the gripper games. Hardly a week goes by that doesn’t see the birth of a newbie gripper startup or a private or university lab announcing new gripper tech.

The investment community is also taking action and is peeling off millions of dollars in backing. Quebec-based Robotiq, in business for a decade and having sold 10k grippers, scored $23 million from Boston-based Battery Ventures.

RightHand Robotics, a newbie with a dexterous and speedy gripper for order picking also picked up $23 million (Menlo Ventures and GV (Google Ventures)).

Another newbie, Soft Robotics, offers a three-fingered, plastic, picking gripper, what the company calls a “new class of robotic gripper” that it recently one-upped announcing an “AI-powered” model. The company has admirers, like Scale Venture Partners et al who anteed up a $20 million investment.

“Soft” is getting very popular in gripperdom. There’s a need for soft, non-rigid materials for food-safe, specialized gripping of things from pork chops to eggs to cupcakes. In December, even the National Science Foundation (NSF) got into the act, investing $20 million in 10 research awards to push forward the frontiers of engineering research in soft robotics.

Grippers will need all of that and more as cobots, unlike any industrial robot before them, are put to jobs heretofore never performed by any robot. Cobots are called upon for material handling, small parts assembly, CNC machine tending, molding operations, test & inspection, gluing, dispensing, welding, packaging & palletizing, screw driving, and polishing…as well as food preparation, handing scalpels to surgeons, milking cows, and camera operator at the Olympics.

Daily, new chores for cobots are attempted by end users, and task-matched grippers to complement those jobs are in high demand.

That means woe to the robot manufacturer that has no credible cobot to offer the market. And woe as well to the gripper manufacturer that neglects to build for them.

Hence, the growing number of new gripper vendors entering the marketplace.

See related: The Gripper Chronicles

Interesting tech

One such new entry, OnRobot (Denmark), is actually the fusion of three startups—one each from Denmark, Hungary and the United States—brought together to pool their tech in order to offer automation users a couple of new looks in grippers: 1. the Gecko Gripper that sticks to surfaces like a Gecko’s foot walking up a glass window, offers adhesion to smooth, flat surfaces (without vacuum); and, 2. RG2-FT with inbuilt 6 axis force/torque sensing, and proximity laser sensors at its fingertips, the RG2-FT is billed as an “intelligent gripper” that can see and feel objects.

Well-known gripper manufacturers are getting aboard the cobot express by offering entire gripper lineups expressly for cobots.

One such established name in the biz is SCHUNK (Germany) founded in 1945, and making grippers since the ‘70s. SCHUNK reacted by developing its Co-act (collaborative actuator) line of grippers that are specifically built for safe human/robot collaboration (HRC). The new entries scored a prestigious Hermes technology award in 2017.

Robotiq (Canada), an established “startup” founded in 2008, has 10k gripper sales under its belt; and recently rolled out a new “adaptive” gripper with integration and increased ease of use in mind, especially for SME end users. The Hand-E integrates wrist camera and force/torque sensing with a 50mm stroke gripper.

Some manufacturers offer specialized grippers, like miniature electric grippers that boast capabilities for precision assembly and inspection. New Scale Robotics claims its tool is the smallest, most precise smart gripper available for cobots. The grippers include sensors and electronics for provide force control, size measurement, and error detection.

In the pipeline & on the verge

Picking things out of a clutter is a capability of interest to the likes of Amazon and WalMart, and MIT researchers have hit upon an answer.

MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), “say that they’ve made a key development in this area of work: a system that lets robots inspect random objects, and visually understand them enough to accomplish specific tasks without ever having seen them before.

The system, called Dense Object Nets (DON), looks at objects as collections of points that serve as sort of visual roadmaps. This approach lets robots better understand and manipulate items, and, most importantly, allows them to even pick up a specific object among a clutter of similar.”

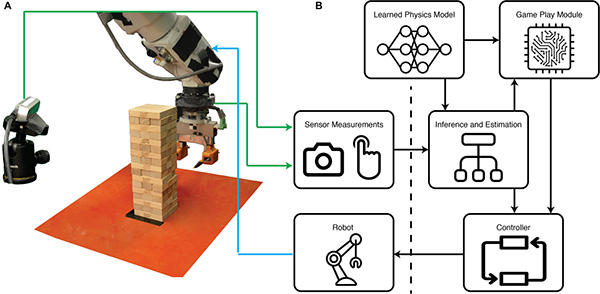

Then there’s MIT again, this time teaching a cobot to beat humans at Jenga. MIT researchers have developed a new kind of robot that’s equipped with a soft-pronged gripper, a force-sensing wrist cuff, and an external camera — all of which it uses to play a mean game of Jenga.

As their paper explains it: “Our proposed approach draws from the notion of an “intuitive physics engine” in the brain that may be the cause of our abilities to integrate multiple sensory channels, plan complex actions, and learn abstract latent structure through physical interaction, even from an early age.

“Humans learn to play Jenga through physics-based integration of sight and touch: Vision provides information about the location of the tower and current block arrangements but not about block interactions. The interactions are dependent on minute geometric differences between blocks that are imperceptible to the human eye.

Chipmaker NVIDIA wants to put cobots into kitchens—certainly places with extreme gripping challenges from opening ketchup bottles to buttering toast.

NVIDIA’s 13,000-square-foot “kitchen” lab in Seattle’s University District will take on job of getting cobots comfortable on the home front. Kitchens are even hard on human hands, let alone grippers. They are, however, places where advanced gripping capabilities would come in real handy…and be well-appreciated by humans.

“We want to ultimately get a robot that can cook a meal with you, or that you can just talk to it and tell the robot what you want to do,” said Dieter Fox, computer science professor at University of Washington, who is in charge of NVIDIA’s kitchen cobot lab project.