What's the Disconnect?

Japan Lags at Deploying Service Robots

Projected as a $35 billion industry by 2022, Japan is not keeping up with professional service robots

“Manufacturing is more automated than in most rich countries, but not service industries.” The Economist

What’s the disconnect?

Why is it that Japan, a country that has a lock on producing over fifty percent of the world’s industrial robots, has such a difficult time knocking out a few good personal service robots? Personal service robots, meaning, those that “assist or entertain humans in their everyday lives,” as opposed to “professional” service robots like those for logistics, agriculture, or hospital operating rooms.

The need, or dire need according to the Japanese government, is certainly evident for personal service robots. CNBC reported that “Japan’s overall population is now declining at the fastest rate globally. The country sells more adult diapers than baby diapers and fewer workers to support an aging population likely leads to poor economic growth.” See accompanying CNBC video report.

Japanese think tank, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI), is out with the dire forecast: Labor Shortage Beginning to Erode the Quality of Services: Hidden Inflation.

Meanwhile, a burgeoning global marketplace for personal service robots is cranking out a robust CAGR of over 38 percent for the forecast period (2018-2022), with revenue projected at $35 billion by the end of 2022.

The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) is forecasting revenues for service robots to eventually eclipse those for industrial robots.

Needed: Robot workers

Over the years, Japan’s robot developers have offered up personal service robots that are cutely interesting but far from practical. ASIMO (begun in 1986) was recently canned, with Honda claiming to be now looking to build robots that can actually do things.

SONY’s dog robot AIBO ($1800) is more an adult play toy than practical helper; PARO, the cuddly, white seal robot ($5000) at least can chat with dementia patients, but that’s all; Softbank’s mousy-voiced, humanoid Pepper ($23000 and 10k units sold) is used by retailers to offer directions and chit-chat.

And then there are velociraptor dinosaur robots as hotel check-in clerks from the HIS Group, which have recently been removed. “When you actually use robots you realize there are places where they aren’t needed — or just annoy people,” explained the hotel’s owner, Hideo Sawada, after firing the entire, rubbery-faced front desk crew.

Only in the land of Godzilla, kaiju, dragons, Astro Boy, anime monsters, and Bunraku puppets, does it seem possible for a hotel owner to say with total conviction, “Yes, let’s use robots that look like dinosaurs to do check in.”

Then again, a hotel’s front desk seems like a great place for a robot. How difficult can it be to dole out a key and then point out the elevator to someone who has already pre-booked a room?

RIETI: Services Cited as Declining in Quality Due to a Shortage of Hands

There’s a disconnect. The scorecard for Japanese service robots is not good, although there are decades of development time and millions of dollars in investments poured into these projects. Lack of success may well have prompted Softbank to buy Boston Dynamics (U.S.) from Google in 2017 for an undisclosed sum.

In fact, foreign service robots may well be the answer.

Tyler Cowen reports that Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) is out pointing a finger: “While gimmicky robots abound, Japan struggles to develop the software and artificial intelligence needed to enable them to perform useful tasks.”

Taking a page out of China’s playbook for acquiring industrial robot technology, Japan, like Softbank has shown, could do likewise for personal service robots. Buy up the many excellent foreign service robots and their base technologies.

Instead of taking in foreign workers, which Japan would like to avoid, bring in foreign robots.

Yoko Takeda of Mitsubishi Research Institute says employment practices make it difficult to replace workers.

For instance:

- Japanese hotels and banks are, by global standards, heavily overstaffed

- Most supermarkets and airlines have not embraced the automated checkouts and check-ins common elsewhere

- Japan’s small and medium-sized enterprises are among the most inefficient in the developed world

- Japan’s elderly, strongly prefer people to machines

Takeda does mention that by 2030, as robots and AI eliminate…jobs, Japan will then have a surplus of workers. Of course, that’s a decade off. What to do in the meantime?

Where are the jobs for robots

As CNBC points out: “In Japan automation is less of a threat to jobs and more about economic survival. As the nation suffers from a chronic labor shortage, it is striving to be the largest robotics-support society in the world.”

According to government estimates, Japan’s service sector accounts for about 70 percent of its economic output, yet labor productivity is 40 percent less than in the U.S. “The contrast puts a strain on the industry sector and now companies like McDonald’s are cutting back on the number of 24-hour outlets.”

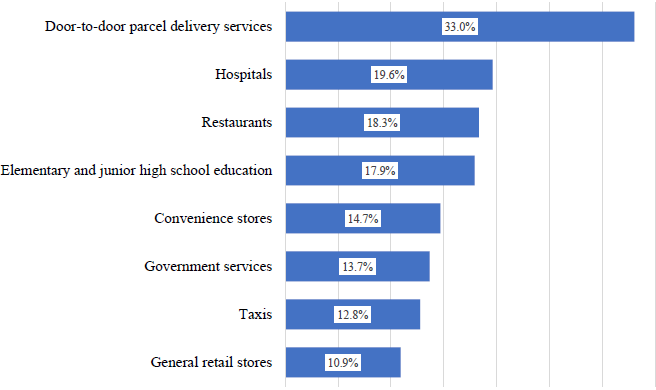

RIETI’s Morikawa Masayuki conducted a survey to isolate exactly which services are most affected by the labor shortage, which would also indicate where service robots are needed most. Called: Lower Quality of Services Due to a Shortage of Hands, this accompanying chart summarizes the report’s findings (See chart: RIETI)