The Rise of Deng Xiaoping

China’s Christmas Miracle & Best Gift Ever!

Keeping the sheen on Deng Xiaoping’s "Big Idea"

They’d been trying to do it in China for 150 years, and they couldn’t. And he did.”

—Ezra Vogel Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China

Annual Holiday Special

Automation’s big break

The central thoroughfare in Beijing—the main drag—is named the Street of Eternal Peace or, in Mandarin, Cháng’ān Jiē.

At Christmas time in 1978, the operative words on Chang’an Street were not eternal peace, but rather, eternal poverty.

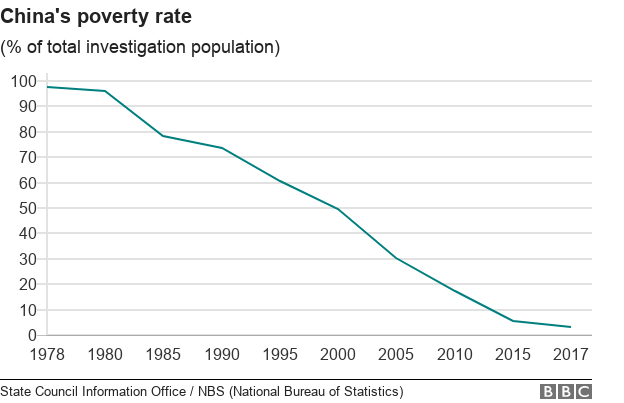

In 1978, 88% of China’s population, after a day of brutally hard work, each worker made less than $2.60 a day, no more than $300 a year.

That meant that in 1978, 88% of all Chinese went to bed poor, and got up the next morning without any chance to be anything other than poor. And their children, they were looking at a future of being no better off than their parents.

That’s a billion human beings awakening each morning to an inescapable, stark reality. And worse for those multitudes was knowing that their children would have to endure the very same fate.

Then it all changed. On December 18, 1978, eight days before Christmas, at Beijing’s Hotel Jingxi, all of that grief and hopelessness would be forever changed for the better.

Modern China was about to be born. The same modern China that the International Federation of Robotics reported bought 168,000 industrial robots in 2020; that’s 3500 each and every week. In 1978, China bought zero.

It’s difficult for anyone, especially in the West, to understand the horrendous journey that China had endured. These same multitudes had just exited the grievous Cultural Revolution. Just previous to that, they had suffered the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-1961; and just previous to that was a revolutionary war, World War II, occupation by Japan, opium wars, and a hundred years of colonial control and humiliation from Treaty of Tianjin in 1858. Generations of poverty were more than ready for some much-needed relief.

At Christmas, China got it, and hasn’t looked back since.

The Miracle at the Hotel Jingxi

Eight days before Christmas, forty-three years ago, China got its best Christmas gift ever. On December 18, 1978, China “tore open the shutters and threw up the sash” on itself to let the light of the world in for the first time since 1949.

What has transpired there ever since is more than astounding; it’s never been done before in human history, no matter how big the country or how large its population.

No one knows what China might look like today if that Christmas gift hadn’t been delivered and opened in 1978. Maybe an epic-size North Korea with “accurate” ICBMs.

One thing for sure is that the International Federation of Robotics wouldn’t be gushing over the tens of thousands of industrial robots sold to China.

The Deng effect

China’s best Christmas gift ever wasn’t dropped down the chimney by an elderly guy in a red suit, but rather by an elderly guy in a gray suit: Deng Xiaoping, the diminutive, 78-year-old Chinese leader from Guang’an, Sichuan province.

Purged three times by Mao, once during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), disappearing from public view until reinstated, Deng became a champion for “reform and opening up” (gǎigé kāifàng).

Purged three times by Mao, once during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), disappearing from public view until reinstated, Deng became a champion for “reform and opening up” (gǎigé kāifàng).

At a Communist Party gathering two years on from the deaths of both Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping rose to give a speech that would set out his vision for China’s future. “We need large numbers of pathbreakers who dare to think, explore new ways and generate new ideas,” said Deng. “Otherwise, we won’t be able to rid our country of poverty and backwardness or to catch up with—still less, surpass—the advanced countries.”

Five days later, at Beijing’s Hotel Jingxi, a small group of party elite agreed to adopt Deng’s new direction for China, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Amazingly, “in 1981, just three years after Deng’s reform project was launched, almost 90 percent of Chinese people still lived in extreme poverty, by the definition of the World Bank. But by 2016, that number had dropped to less than 2 percent.”

By 2013, China’s middle class was 500 million; its urban mass, hovering just below middle class and striving to make the jump to middle class, was another 500 million.

This middle class has money and is buying. A look at the extraordinary rise of appliance maker Haier shows the middle-class effect on China’s industry.

Haier Group, “in the last 35 years has been transformed from a failing state-owned refrigerator maker to the world’s largest white goods company with $32.8 billion in sales in 2020. Its rise to global dominance was cemented in 2016 when it bought GE Appliances, for decades a symbol of high quality.”

The Father of Modern China

“I developed an enormous regard for the extraordinary little man with the melancholy eyes.” — Henry Kissinger

Haier is not an exception; it’s the rule in China’s industrial growth.

As Bloomberg recently pointed out, China must now try to avoid falling into what economists call the middle-income trap (see: Dani Rodrik: China’s Boldest Experiment), where per-capita income stalls before a nation becomes rich. “Usually that happens because rising wages and costs erode profitability at factories that make basic goods like clothes or furniture, and the economy fails to make the jump to higher-value industries and services.”

Only five industrial economies in East Asia have succeeded in escaping the trap since 1960 (World Bank): Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan.

China, for this year’s Christmas gift, is hell-bent on becoming the sixth.

Such a leap is impossible to make without modernizing industry with robot-driven automation. In his 2014 speech on core technologies, President Xi Jinping called for a revolution in robotics; and with that speech made a commitment to robot-driven automation. A speech otherwise impossible without Deng Xiaoping’s Christmas Miracle.

Here in 2021, Xi and China continue to live up to that commitment, as this recent CNBC headline reports: Why China is spending billions to develop an army of robots to turbocharge its economy. Plainly, the robots and automation are necessary; there are no substitutes, and there’s no going back to depending solely on human labor. Billions of dollars are flowing from the government to subsidize robots, and the flow will continue unabated, even in the face of a trade war.

However, China’s best Christmas gift ever from Deng Xiaoping now needs a critical upgrade, which has now fallen to Xi Jinping to deliver.

The Xi effect

After forty years of “reform and opening up” (gǎigé kāifàng), which besotted China’s skies, polluted water supplies, and poisoned agricultural lands larger than the entirety of Great Britain, a major cleaning of the tables is long overdue.

Even corruption, which drains away the equal of China’s entire defense budget, needs constant rooting out.

That gargantuan undertaking has fallen to 68-year-old Xi, who, like Deng, also ran afoul of the Cultural Revolution, and also survived it. For those lifted out of poverty, it will be up to Xi to sustain them with a quality standard of living.

Ensuring the food supply, trustworthy pharmaceuticals, dependable medical care, reliable transportation, and high-quality, consumer goods, have all fallen on his shoulders.

So too has “reskilling” workers displaced by robot-driven automation. “By 2020, China’s Ministry of Education had hoped to enroll 23.5 million students into three-year vocational programs designed for the new economy.” COVID has short-circuited much of that effort.

And all the while, the vortex of the middle-income trap swirls menacingly closer.

Automation is how Xi will maintain the sheen on China’s best Christmas gift ever.