Skill Shift: Automation & the New Workforce

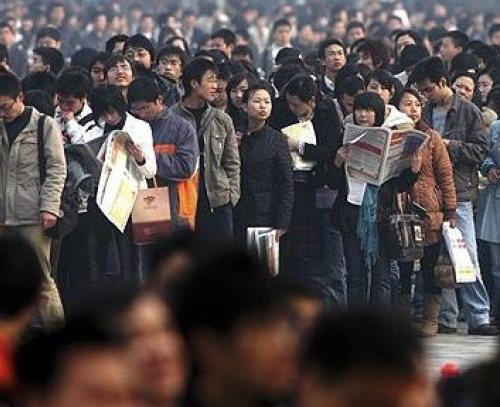

The Future of Work in China: Chasing Jobs

How to Say “Ausbildung” in Mandarin? Could the German dual-learning apprenticeship program help millions of China’s displaced workers to survive and thrive in a future of Industry 4.0?

学徒

It’s a given that manufacturing automation, now and more so in the future, will displace millions of China’s factory workers with robots and automated machinery. It’s the feared outcome of Industry 4.0—the digitalization of manufacturing—that’s ramping up in all industrialized countries worldwide.

With artificial intelligence (AI) recently thrown into the Industry 4.0 mix, more than just factory workers will be getting displaced in the not-too-distant future. Three of Japan’s major banks (Mizuho Bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group) have announced future departures of over 33,000 employees due to automation. In the U.S., Wells Fargo has just announced that it will shed 26,000 employees because of automation.

Displacements of workers in a country the size of China, especially with its population of 1.3 billion, might well magnify joblessness via automation to a level unseen in human history. Then again, it might not.

With the multi-billions of dollars China has spent over the past five years buying up some sixty-odd German technology companies, there is a hidden benefit locked away in these German acquisitions that just might be as important as the acquired technologies; a benefit especially important to the tens of millions of Chinese looking down the barrel of a pink slip.

Hiding in plain sight

The Germans call it “ausbildung”, meaning apprenticeship, but “a very special dual-learning apprenticeship system of standardized, superior training—both formally in schools plus on-the-job training” that allows its citizens to get recognized for specific jobs.

“In Germany, everything from selling cars to building pianos and harpsichords has its own practical technical schooling, testing and qualifications. It is a system that experts say allows a highly capable workforce to earn middle-class wages, enjoy job security and bring a high level of expertise to jobs that increasingly rely on more than just muscle, nimble fingers and endurance.” Every country could use a large dose of that.

“Ausbildung” is a readily accepted part of German culture and kept in very high regard by its industry and business. In fact, “ausbildung” is institutionalized in every German company, including all those swept up in the great Sino-German sell off. In short, there’s an apprenticeship infrastructure extant in China that China can tap into to copy the Germans.

Of course, neither China nor anyone else, for that matter, will ever duplicate the robust Germanic brand of “ausbildung”, which has a lineage arching back to the 1520s with the Swiss-German Paracelsus. Paracelsus, a contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci, has been tabbed as the “father of chemistry,” the “Luther of Medicine,” the “founder of modern toxicology”, and the “godfather of modern chemotherapy,” and was the guy who infused the critical importance of both “observation and received knowledge” into German technical learning. The font of that much-revered byproduct “German quality”.

The Germans have a lock on “ausbildung”, but, nevertheless, it’s basically exportable. BMW exported it to South Carolina where it’s doing just fine, albeit in its own strange American way.

China has yet to recognize and act upon this remedy for impending worker displacement even though it is sitting right there in country.

Apprenticeships more than just a job

Although, Matthias Risler and Zhao Zhiqunas point out in Apprenticeships in China that reports on apprenticeships in China are as old as the Tang and Song Dynasties (618 – 906 AD & 960 – 1279 AD respectively), such apprenticeships were for skilled crafts and not general industry. Even in the middle of the 1980s, “apprenticeship was not specifically considered, as the Government laid down its policy of “first train – then employ”, with the purpose of rationalizing the large economic and social conglomerates and redefining institutions, factories and other types of economic and social entities.”

In 1985, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party announced the “Decision on the reform of the education system” that introduced a “double certificate” system for trades or vocations, but it was light years off from the scope and rigor of “ausbildung”.

And the German apprentices are no slouches: with the worry and angst over a clear career path taken care of in advance, apprentices are free to dedicate themselves to their new professions. And they do; the results are remarkable for learner, sponsoring company, the products manufactured…as well as for the government.

“Ausbildung” is not only a boast in confidence for every apprentice, but it’s also cheap! “The cost of the tuition at the trade college and the 12 weeks of missed work are paid for by the federal employment office under a program designed to train older adults. In 2015 the program helped train more than 24,000 people in Germany at a cost of roughly $206 million.” That rings in at $8500 per apprentice.

Close, but no cigar

To its credit, China has been running a variant of this student/real-world hookup, but in “reverse” in agriculture for ten years. Beijing’s China Agricultural University has been running the Science & Technology Backyard (STB) project in villages across the country, allowing students to apply their academic knowledge to maximize crop yields.

For a country with 20 percent of the world’s population and barely 10 percent of the world’s arable land, the impact of the STB program has been staggeringly successful.

“The aim is to efficiently transform academic achievements into farm productivity, and at the same time to enhance students’ ability to apply knowledge in a practical way,” says Zhang Hongyan, an associate professor at China Agricultural University.

Now fold in ChemChina’s $43 billion acquisition of Syngenta, the Swiss pesticides and seeds group, and “ausbildung” would take on a decidedly strong position for creating jobs as well as improving domestic agricultural output.

“Ausbildung” and reskilling

Germany’s dual-learning apprenticeship program isn’t just for students creating a new career track for themselves; it can also change career tracks for anyone at just about any age. Anyone with the will to change can reskill for a new career. See video (above) of 30-year-old German apprentice.

Reskilling is a powerful antidote to our age of job-loss hysteria brought on by robots, automation and AI. First off, reskilling offers hope, which is respite from panic documents like the 2013 Oxford Martin study that excised “702 detailed occupations” together with millions employed therein.

Job loss, and its attending hysteria, was somewhat abetted by studies like the 2019 McKinsey Global Institute: Skill Shift:Automation and the Future of the Workforce The “Jobs Gained” in its title was refreshing. It concluded that job loss to automation wasn’t as severe as the Oxford Martin study, but rather, “parts” of all jobs, the repetitively boring parts, would be handed over to automation, with humans retaining most of the hours worked in any given work week.

Now comes the World Economic Forum’s Jobs of Tomorrow: Mapping Opportunity in the New Economy It forecasts that 75 million jobs will be forever gone by 2025, succumbing to artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automation. However, on the sunny side of the street will be “133 million new jobs [that] may be created as organizations shift the balance between human workers and machines: a net gain of 58 million.” Hooray for humanity!

The real good news is that since 2013 job-loss experts have tempered their prognostications of a jobs’ bloodbath. Now we’re looking at “net gains” in jobs, although no one knows what these future jobs are going to be.

Throughout all of the employment reports over the past five years, it’s easy to see the thread of importance that “ausbildung” could bring to the future of work. By its very nature “ausbildung” is proactive and not reactive to change.

Instead of recoiling in horror every time technology disrupts work, Germany reskills, and moves on.

Partly as a result, Germany is enjoying low youth unemployment as well as its best unemployment numbers in 37 years.

China might do well to look behind its acquired German technology for the golden thread of “ausbildung”, which in Mandarin is 学徒.