Malaysia’s Robot City Gets Cranking

Seeking its own piece of Industry 4.0, Malaysia looks toward digitally-driven manufacturing for an edge in productivity…and a better future

New strategy, same old game

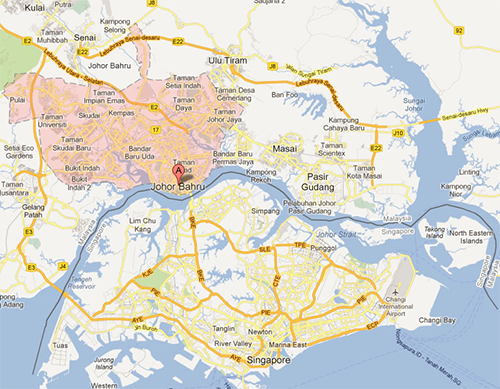

Malaysia’s Johor Bahru (New Johor) is the capital of the state of Johor, and sits cheek to cheek with Singapore, some 2,000 feet away across the Causeway Shoals in the Johor Straight.

Because of recent deals with China, and meetings with Korea as well, 2.5 square miles of west Johor Bahru is slated to become a multi-purpose robot city. The robot city’s purpose is to further the government’s objective of creating high-income jobs and accelerate economic growth in the state of Johor, said Kamaruzzaman Abu Kassim, president and CEO of JCorp, the city’s builder.

Dubbed Robotic Future City, it represents a deal in the making between the Johor government subsidiary in Malaysia, Johor Corporation, the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA), and China’s leading robot builder Siasun Robot and Automation that will see Siasun invest $3.5 billion.

The robotics hub, which the Malays refer to as a “first ever” such hub for Malaysia, “will include a planned regional base for Siasun, including robotics equipment and components, parts production facilities, research and development (R&D) labs, and a service center.”

The country’s industries are prime targets for a robot makeover. With a robot density of only 34 robots for 10,000 workers, there are barely 40,000 robots in the entire country of 32 million people. More telling is the ratio between automobile manufacturing and other industries: 129 robots per 10,000 workers at car plants; 19 robots per 10,000 workers everywhere else.

The everywhere else is mind-boggling because, for example, Malaysia’s electronics industry—the country’s largest manufacturing sector—is squarely in that low 19 robots per 10,000 workers. The electronics industry makes everything from semiconductors to TVs to computer keyboards, computers, computer peripherals, telecommunications and electronic office equipment, and accounts for over 36 percent of the country’s exports. It’s also a growing market for robots and cobots, as it is in the rest of the world.

5,000 firms from more than 40 countries have facilities in Malaysia: Intel, Texas Instruments, AMD and ST Microelectronics, Silterra, Unisem, Inari and Globetronics, plus consumer electronics from major Japanese and Korean firms. Sony’s largest TV production plant is in Kuala Lumpur.

Pharmaceuticals, also ripe for robot disruption, have a heavy presence as well: Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Roche, to name a few.

Under the Eleventh Malaysia Plan, 2016-2020, the government aims to increase productivity in manufacturing through a two-pronged strategy of “increasing automation and enhancing workforce skills development”. Robot City will become critical to the success of the plan.

Compared with its ASEAN neighbors, Malaysia is doing well with the third highest GDP per capita among the ten nations (trailing only Singapore and Brunei): $9,813 (2017), $439 higher than in 2016. By comparison, Thailand’s is roughly $6,800; Vietnam’s is $1800. (See: MAPS for ASEAN nations)

The country’s GDP for 2017 was $314 billion, which, sadly, is just a few billion more than the country’s recently revealed debt of a staggering $248 billion.

The people factor

Robot City may pop into being, Malaysia may import thousands of robots—and surely with electronics and pharmaceuticals—there’s a ready industrial need to improve productivity via robotics. However, there is a scant workforce capable of operating all these robot wonders. The breakdown: 75 percent semi-skilled, 7 percent low skilled, and 18 percent skilled.

“Malaysia has yet to evolve from mere assembly, testing, design and development that are common in component parts and system production, suited to support high tech sectors.”

In short, there’s little of a robotics ecosystem in Malaysia. The Malaysian Robotics and Automation Society (MyRAS) has published a study that identifies and addresses the near-term demands of the robotic industry in Malaysia. It’s extensive, pointing out a shortage of 160,000 robotics professionals in five skills areas: managers, technicians, engineers, supervisors, and operators; the need for 200 vendors/service providers; and shortages of specialized knowledge in seven areas ranging from algorithms to IoT.

Such raw workforce deficiencies coupled with such a great opportunity as robotics presents may encourage Malaysia to take an unconventional path to building an ecosystem, even a rudimentary one.

Going for cobots over robots, because the former offer an easier learning curve, could be an option. Something is needed to compress the timeline of opportunity.

See: Cobots: Every Factory’s New Best Friend

Bringing outsiders into the country is a possibility. However, as Manoj Menon, managing director of Frost & Sullivan in Johor, told the Oxford Business Group: “Attracting talent is one of the major challenges for companies operating in Johor: a weaker ringgit makes local salaries uncompetitive compared to those offered in neighboring Singapore”.

According to Manoj, bringing internationally recognized private universities into EduCity (special learning center in the Iskandar special economic region in Johor) to teach-up the needed skills could be an option if the government made a commitment to do so.

Whichever the road taken by Malaysia, it needs to be taken in a hurry. Thailand now and soon Vietnam will be pacesetters in ASEAN Industry 4.0. Malaysia has a chance to join them.