Learn, Unlearn, Relearn!

AI and Robot Hysteria Get a Little Clarity

Recent OECD research on how best to transit into the new world of automation

Some things never change:

“March of the Machine Makes Idle Hands: Prevalence of Unemployment with Greatly Increased Industrial Output

Points to the Influence of Labor-Saving Devices as an Underlying Cause.” —New York Times, February 26, 1928

Transiting into automation

A new report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) titled, Automation, skills use and training, is out offering some clarity for those worried about humanity being helpless as robots and Artificial Intelligence (AI) sweep us under the rug.

The 125-page OECD report is meticulously researched, and adds lots of commonsense and straight thinking to the overheated rhetoric that’s got folks everywhere worried about machines jeopardizing the future of humanity…and its workplaces, careers, and jobs.

The report also does a good bit of finger pointing as well; kindly finger pointing, but still, it calls out groups that usually get a pass, like those who run and administer educational institutions in the more than two-dozen countries mentioned in the report.

Although classrooms, lecture halls, laboratories and training facilities may well be engines of excellence in technology, the offices of higher ups in many of these institutions are far from being engines of excellence in realizing technological trends and adjusting the supply of graduates: “If educational institutions had been quick to realize this trend and adjust the supply accordingly,” claims the report, “the developments might have looked very different today.”

The remedy, say the authors: “It is critical to understand that the effects of technological change on the employment and wage outcomes of citizens are deeply dependent on how well educational and training institutions can anticipate demand shifts and how quickly and substantively they can respond to them. While it may be difficult to control the diffusion of technologies, it is certainly possible to mitigate their “dark side” by designing timely and adequate institutional responses.”

How did we get to now?

It’s been a quick six years since that watershed 60 Minutes episode (2013), Race Against the Machines, set off a firestorm of worry about robots stealing jobs.

Millions probably still recall Erik Brynjolfsson and Andy McAfee from MIT’s Sloan School getting grilled about jobs and robots by program host Steve Kroft.

“Technology is always creating jobs. It’s always destroying jobs,” replied Brynjolfsson to a Kroft query. “But right now the pace is accelerating. It’s faster we think than ever before in history. So as a consequence, we are not creating jobs at the same pace that we need to.” At which, in a seeming nanosecond, McAfee added: “And we ain’t seen nothing yet.”

That did it! The sense of imminent foreboding in “we ain’t seen nothing yet” was scary headline material for years thereafter.

The same year, 2013, the Frey-Osborne Oxford study detailed the 702 at-risk occupations and the 47 percent of U.S. workers with a high probability of being jobless.

Like the hysteria of the 1980’s angst over “nuclear winter”, automation was going to be a “robot winter” of terrible unemployment and social unrest that would do us all in.

Manufacturing jobs were going to be goners; it was robots working in the dark 24×7.

Reality, however, hasn’t lived up to the fear mongering. What’s up? Just as “nuclear winter” was eventually shown to be bit far-fetched, might robot winter? The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data show that over the “past 12 months [2018], industrial domains created twice as many jobs” as did the healthcare sector, IT, retail, leisure, and transportation. “Manufacturing alone added 25 percent more jobs than did ‘professional and technical services.’”

Talent overhaul

Of course, nice as they are, “twice as many jobs” and “25 percent more” don’t mean much when stacked against the massive skills gap. “In the United States, there’s a record number of jobs open: around 6 million. That’s just about one job opening for every officially unemployed person in the country.”

Globally, the skills gap affects all developed countries.

Filling that skills gap is the future! It’s the future not only for the U.S. but for the EU and Asia. And according to the OECD report, training, re-training, and re-qualification of workers away from jobs that are “highly automatable to jobs less automatable” is the key to success in filling the skills gap.

“In a Deloitte survey, 39 percent of large-company executives said they were either “barely able” or “unable” to find the talent their firms required.”

In a remarkable and admirable corporate-wide retraining endeavor, AT&T has elected to retrain its current employees…140,000 of them! “The average tenure at the company is 12 years—22 years if you don’t count people working in call centers.”

“Since 2013, when the initiative began, AT&T has spent $250 million on employee education and professional development programs and more than $30 million on tuition assistance annually. AT&T estimates that, all told, 140,000 employees are actively engaged in acquiring skills for newly created roles (And the expectation is that every four years they’ll change roles again.)”

Retraining bias

Not everyone is as generous with retraining as AT&T. The OECD report sees most employers exhibit a degree of bias in their retraining programs.

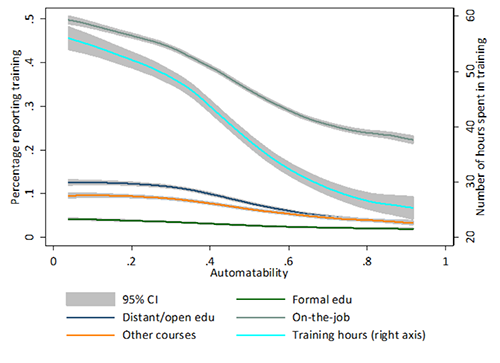

“The first finding that is consistent among most surveyed countries is that workers at risk of automation receive less and not more job-related training than other workers. This is the case both with training provided by employers (on-the-job training) and training obtained outside the firm (formal education, online courses etc.)”

So, if you are an order picker and a robot arrives on the scene that will automate 100 percent of your job, you’re less likely to be offered re-training; which is bad news because “AI appears to affect low-skilled jobs more significantly than previous waves of automation.”

“The risk of automation declines with the level of education, with the level of measured skills and with the wage level across almost all countries, suggesting that this wave of automation is skill biased.”

The cut-off point appears to be 30 percent. If the ease of automating a job goes beyond the cut-off point, the worker is less likely to be offered re-training.

Post-60 Minutes

We’ve come a long way in accommodating work to automation since 2013. According to the OECD report, everyone to some degree will be affected by automation as AI and robots become smarter and more adept. There are chunks of every worker’s workday or work week that are boringly repetitious and easily automated that workers would enjoy offloading to a machine. That’s millions of work hours that will be more efficiently accomplished through automation, freeing up those same millions of hours for workers to apply to more cognitive tasks.

Over time, as AI and robots evolve their capabilities, those chunks of automation will in all likelihood tend to grow larger, swallowing up more and more of the workload. Learning how to stay ahead of automation and keeping skills relevant will be a part of everyone’s career.

Under constant pressure from the advances of automation, many job functions will simply disappear. Machine tending, for one, is history…or almost so. The job will be gone, and so too the hours spent training people to do it.

Historically, technology tends to keep ahead of the work automation wave by creating ever more industries with ever more new jobs. For example, apps weren’t invented until the late 2000s, and now app development is a multi-billion dollar industry employing tens of thousands of people, many of whom didn’t study the tech in college, either. They all needed to be trained.

As Mark Mills, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, writes in Robots to the Rescue—of Manufacturing: “Before cars were invented, there was no demand for cars—or for paved roads. Before plastics, there was no demand for plastics. Chemical industries employed only 100,000 people early in the 20th century and now employ nearly 1 million Americans.”

No matter where anyone is on the automation chain, lifelong learning is now a critical necessity. A way of life!

Institutions will need to be more aware of and responsive to demand shifts. Employers and government will need to work together to reasonably assure that no worker is left behind, even if job automation potential is higher than 30 percent. And workers will need to be very aware that their job is not secure for life, that constant attention to “upskilling” themselves is a necessity.

As Alvin Toffler put it nearly fifty years ago: “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”