Cut-flower cultivation the size of New Jersey. An automated future could treble its value

Automating China's

$11B Cut-Flower Industry

Demand has been so great that there are now about 300,000 farmers cultivating 1.5 million hectares of flowers in Yunnan, up from just a few dozen growers and less than 10,000 hectares back in the 1990s.”

— Mao Haipeng, Yunnan Dounan Flower Industry Group

"Yunnan Province boasts over 300 varieties of flowers, with seven out of 10 flowers in China being produced here. The exquisite floral diversity from Yunnan reaches over 50 countries and regions, contributing to an impressive export value of approximately $470 million dollars the first quarter of 2024," said Qian Chongjun, CEO of Yunnan Dounan Flower Group.

300,000 flower farmers

Virtually overlooked in China’s mad dash to automate nearly everything is the country’s cut-flower industry—a/k/a floriculture industry.

According to China Horticultural Business Services, China’s floriculture industry is valued at more than $11 billion, with 90 percent of the fresh flowers produced consumed in China.

Automation could treble the value of China’s cut flower business plus expand its reach well beyond the country’s borders. Both of which the flower industry wants to accomplish in the not-too-distant future.

Although China’s cut flower industry began in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong in 1984, it is now principally centered in Yunnan province, which is nestled up against Myanmar and Laos, and where there is zero automation in planting, cultivation, harvesting, or in the delivery of fresh product to market. All of which need to change if the industry hopes to reach its goals.

In 1990, Yunnan had 38 square miles under cultivation for cut flowers; by 2017, floriculture had blossomed to nearly 300,000 farmers cultivating over 7,000 square miles (about the size of New Jersey). Daily, the province sees over 10 million of its flowers sold through auction at the cavernous Dounan Flower Market located in Yunnan’s capital of Kunming.

By way of comparison, the world’s biggest cut-flower auction at the Aalsmeer Flower Market (Netherlands) sees 16 million auctioned daily.

Yunnan accounts for 70 percent of the cut-flower trade in China, and is now looking to become Asia’s largest as well as to become a key player in global floriculture.

Here’s the Dounan Flower Market (Yunnan, China) in action:

Only 7,000 flower shops?

Incredibly, the majority of that 90 percent of the flowers sold in China are sold into just four geographical areas: Shanghai, Beijing, Zhejiang and Guangdong, and where, understandably, most of the country’s 7,000 flower shops are located.

The incredible part is that China is massive and its population over one billion, which means the growth potential is off the charts. Especially so now that China has a massive middle class (over 500 million) with disposable income enough to afford cut flowers.

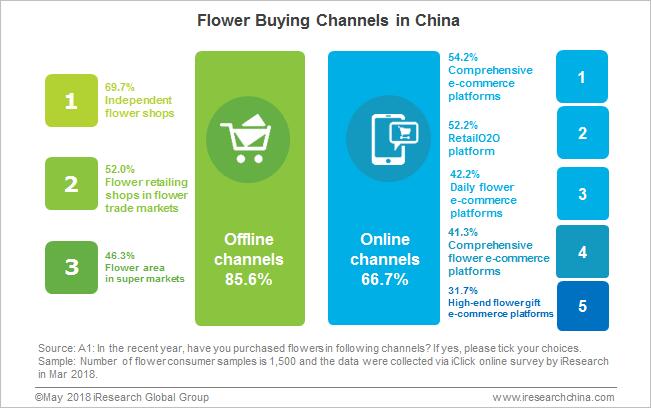

E-commerce, as with everything else in China, seems to be a winning formula for cut-flower sales. Internet consulting firm iResearch estimates China’s cut-flower e-commerce market expanded from $188 million in 2013 to $1.9 billion in 2017 and is likely to close in on $7.8 billion by 2021.

In a recent interview, Mao Haipeng, from the Yunnan Dounan Flower Industry Group, said that “a large part of the growth is thanks to China’s expanding middle class, who increasingly see cut flowers as a part of daily life rather than luxuries reserved for special occasions…and this was part of a natural shift as China’s economy developed and families started to have more disposable income for something that might have been seen as wasteful in the past.”

Automation

“Quality is the industry’s weak spot,” Mao said. “We are getting close to Europe in terms of transaction volume, but the average price is not even close.”

Wang told the South China Morning Post that “the root of the issue was poor growing and processing technology. Unlike their counterparts overseas, farmers in Yunnan have only started using greenhouses, which can protect plants from pests, disease and the cold.

“[But] farmers here either have no awareness [of the technology] or are reluctant to use it because of the costs.”

“iResearch said logistics also needed to improve, with the domestic industry only now starting to use refrigeration to store and transport the blooms.”

China could learn much from the automation technology from the little big man of the cut-flower export trade, the Netherlands, which boasts a 52 percent share.

SURROUNDED BY ROSES, NOT A ROBOT IN SIGHT

A bit of irony?

The irony in Dutch lily growing is an interesting example. The Dutch sell over 300 million lilies annually, about half of which go off to the UK for a neat $66 million. The most prized and most expensive of those millions of Dutch lilies is the Regal Lily (lilium regale), which in 1903 was imported from guess where? China.

If China had had a patent on the Regal Lily, it would now be owed some 115 years’ worth of royalties.