Pink Slips for Old Technology

Studs Terkel, Robots & Our Jobs

Technology reaps…and sows, and we need to be ready faster for both!

Work fit only for robots?

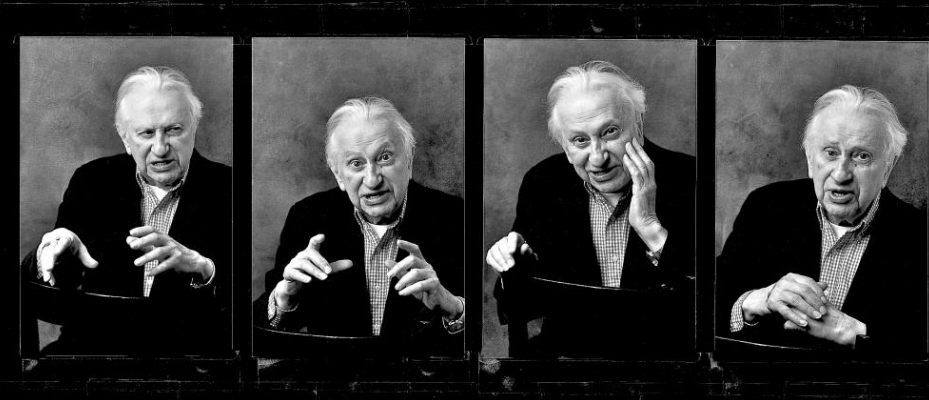

Studs Terkel spent forty-five years of his life interviewing working people about their jobs.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning writer asked a lifetime of questions resulting in 9,000 audiotapes for his Studs Terkel Show that aired over radio station WFMT in Chicago. That’s about 200 interviews a year for over four decades. The interviewees ranged from titans like Simone de Beauvoir, Bertrand Russell, and JK Galbraith to simple, ordinary working folk like Hobart Foote of Gary, Indiana.

AI, with a neat algorithm that could parse audiotape, might well tell us lots of interesting things about these people and the patterns of their work lives. Terkel was his own algorithm, and he put the best of himself into a bunch of books on people, their jobs, how they worked and why.

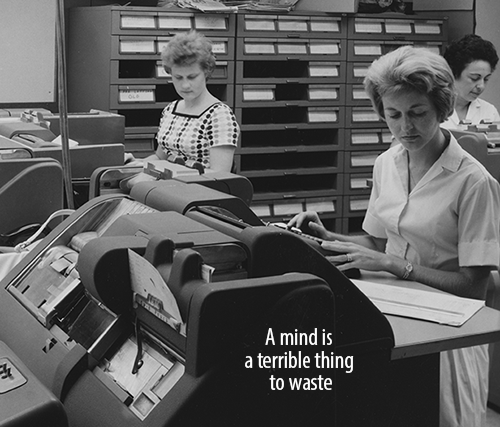

One of the themes that reoccurs regularly in the interviews is that of people feeling that their jobs were mindless, repetitive, boring, and most certainly a job, as more than a few said, fit only for a robot. Jobs that they prayed their children wouldn’t have to endure to make a living. But thank God for that mindless job, because without it there’d be no bread on the table at home.

In one of his most famous books, Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, Terkel distilled the essence of what he was hearing about jobs from those interviews: “It is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying. Perhaps immortality, too, is part of the quest. To be remembered was the wish, spoken and unspoken, of the heroes and heroines of this book.”

Pink slips for old technology

Most of the people that Terkel lovingly and skillfully interviewed are gone, and so too are their mindless jobs. Fortunately, no one has to tell their kids to get a job as a key punch operator or to stand all day at a turret lathe or learn to operate an elevator. Technology has already taken on that task for us.

Technology, as it has since the days of Stephenson’s locomotive, was the grand reaper of all those jobs fit only for a robot. Today, technology is still at it, and always will be still at it, reaping…and also sowing.

These days, however, technology’s innovations and deployments are accelerating, and the reaping and sowing are accelerating right along with them. Ten years from now we’ll look back and think that the acceleration was snail slow, and it’ll be true.

According to Ray Kurzweil in his The Singularity Is Near, technology is an evolutionary process, like biology, only it moves from one invention to the next much faster.

Technology swept away the toil of key punch jobs, replaced them, and then replaced the replacements, and so on.

Technology goes beyond mere tool making, writes Kurzweil; it is a process of creating ever more powerful technology using the tools from the previous round of innovation.

Terkel died in 2008, but if he were around today, his interviews would offer him a ringside seat at the epicenter of the new phenomenon of high-speed workplace disruption. His frequent interviews would readily display the pattern of Kurzweil’s onrush of technology.

Clearly, Terkel would quickly deduce that people need to mirror the acceleration process just to keep up with preparing themselves for the rapid changes ahead, or miss the opportunities resulting from the ever-newer technology. Or worse, suffer the consequences of being too slow in an age of fast-or-else transformation.

Now a decade on since his last interview, fast-or-else transformation has a robot or AI or a combination of both replacing the person; technology is in Kurzweil’s accelerated reaping mode, but also in accelerated sowing mode as well.

Ben Pring, director of Cognizant’s Center for the Future of Work and co-author of What to Do When Machines Do Everything, sees 19 million positions in the U.S. alone that will be automated out of existence. All global industrialized economies will experience similar job losses. That’s the tech reaper at work. As for tech sowing, the Cognizant Center forecasts 21 million new roles, with the majority of existing jobs likely to be enhanced. “Work will change, but it won’t go away,” says Pring.

The mountain yet to climb

The “staying but changing” part of the new age of transformation is ramping up, as CNN blarred in this headline: U.S. has record 6 million job openings, even as 6.8 million Americans are looking for jobs. Worldwide, more or less the identical job disconnect is being seen ever more frequently: The skill sets on people’s resumes don’t match what’s in the Help Wanted adverts.

The following “Was there anybody Studs Terkel didn’t know?” excerpted from Humanities Magazine (2015).

The famed broadcaster and author had enough friends and acquaintances to last several lifetimes, so it’s no surprise when he pops up in Michael Moore’s 1998 film The Big One.

Midway through the documentary, in which Moore travels the country hawking his book Downsize This!, the provocateur filmmaker drops in on Terkel at 98.7 WFMT, the Chicago radio station that was home to Terkel’s interview program for over four decades.

Excited to have him, Terkel cues up John L. Handcox’s classic folk song Roll the Union On, which Pete Seeger, who ought to know, once called, “a great picket line song. One of the greatest ever.” The song is rousing, but it is Terkel—and his endearing, revealing reaction to it—who captivates.

“One more verse!” he barks several times to an off-camera radio crew. Outfitted in his signature red sweater—his white-maned head dwarfed by oversize earphones—he moves his arms to orchestrate the music, never mind that it’s a recording.

His microphone before him, Terkel stammers and murmurs the lyrics: “We’re gonna roll . . . We’re gonna roll the union. . . .”

At this moment, the rascally radio hand is north of eighty, but he’s no old man lost in a reverie. In fact, he is downright sprightly.

With impeccable timing, he brings the volume down by lowering his hands. Then, effortlessly, he transitions to his guest—a native, of course, of Flint, Michigan: “Hearing that song of the thirties, of the Flint sit-down strike of labor, the CIO” Terkel says, stressing thirties and C-I-O, before drawing out the connection, “seated next to Michael Moore.”

Some may argue that Moore is unworthy of so grand an introduction, or that Terkel’s sentiments reveal an unbecoming naïveté. But it’s hard to not be won over by Terkel’s joyful display of conviction.

Here, one thinks, is a contented man, secure in his take on history and pleased as punch to have cast his lot with the downtrodden. He could be among those who, for Carl Sandburg, exemplify “happiness” in his great poem of that title: not the “famous executives who boss the work of thousands of men,” but rather the “crowd of Hungarians under the trees with their women and children and a keg of beer and an accordion.”

Born in New York City in 1912 as Louis Terkel, he affixed “Studs” to his name—he writes in his 2007 memoir Touch and Go—after he graduated from law school at the University of Chicago and was trying to make it as an actor. Cast in Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty, he writes, “two other guys in the cast were named Louis. . . . At the time, I was entranced by the writings of James T. Farrell and his Studs Lonigan trilogy. Everyone started calling me Studs.”

And the name does justice to Terkel’s one-of-a-kind life, too: Just as his law degree did not stop him from pursuing acting, the blacklist—which resulted in an early television show, Studs’s Place, being canceled—did not dampen his determination to broadcast, loudly, his particular brand of politics. In 1952, WFMT’s The Studs Terkel Program began airing, and it did not cease until some forty-five years later, in 1997. (“I’m not suggesting you be on the blacklist,” he said in 1999, in an interview with the Archive of American Television, but “were it not [for] that I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing today.”) His personal life—like his professional life, and like his political beliefs—was a study in continuity: His wife, Ida, died in 1999, after more than sixty years of marriage.

There aren’t many media figures who were alive during the Woodrow Wilson administration and yet remain influential in the twenty-first century, but Terkel is one. And his admirers are an au courant bunch, ranging from crime novelist Walter Mosley to radio host Garrison Keillor. Terkel’s part in the development of the oral history form—that is, books in which interview subjects tell their stories without assists from a narrator—is widely acknowledged.

About a week after Terkel’s death on October 31, 2008, Ira Glass tipped his hat on This American Life. “Oral histories were around before Studs started doing them,” Glass said at the time, “but he pretty much redefined them and did them so amazingly well that anybody who comes after can’t help but be influenced.”

Alex Kotlowitz, acclaimed author of There Are No Children Here, was a friend, and he, too, sees Terkel’s impact as stretching far and wide. “You look at [Haruki] Murakami, the Japanese novelist, wrote a book called Underground, which was a collection of kind of oral histories about the gas attacks in Tokyo, and he gives a nod to Studs at the very beginning of that book,” Kotlowitz said, adding that Terkel “created this genre.”

Extraordinarily prolific, he certainly contributed to it: Concurrent with his radio career, which kept him busy five days a week, Terkel assembled a formidable bunch of oral history-style books, among them the best-selling Working (1974) and the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Good War (1984). Others concerned the Great Depression (Hard Times, published in 1970), Chicago (Division Street: America in 1967), and the specter of senescence (Coming of Age in 1995).

In the end, the difference maker between technology reaping and sowing is going to be all about people and what they know. Learning is always a good place to start.